https://github.com/cpq/embedded-network-programming-guide

A complete guide for network programming on microcontroller devices

https://github.com/cpq/embedded-network-programming-guide

Last synced: 11 months ago

JSON representation

A complete guide for network programming on microcontroller devices

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/cpq/embedded-network-programming-guide

- Owner: cpq

- License: mit

- Created: 2023-12-30T18:12:46.000Z (about 2 years ago)

- Default Branch: main

- Last Pushed: 2024-08-24T20:26:36.000Z (over 1 year ago)

- Last Synced: 2025-01-19T15:46:31.763Z (about 1 year ago)

- Size: 149 KB

- Stars: 193

- Watchers: 12

- Forks: 19

- Open Issues: 1

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

# Embedded network programming guide

[](https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT)

This guide is written for embedded developers who work on connected products.

That includes microcontroller based systems that operate in bare metal or

RTOS mode, as well as microprocessor based systems which run embedded Linux.

## Prerequisites

All fundamental concepts are explained in details, so the guide should be

understood by a reader with no prior networking knowledge.

A reader is expected to be familiar with microcontroller C programming - for

that matter, I recommend reading my [bare metal programming

guide](https://github.com/cpq/bare-metal-programming-guide). I will be using

Ethernet-enabled Nucleo-H743ZI board throughout this guide. Examples for other

architectures are summarized in a table below - this list will expand with

time. Regardless, for the best experience I recommend Nucleo-H743ZI to get the

most from this guide: [buy it on

Mouser](https://www.mouser.ie/ProductDetail/STMicroelectronics/NUCLEO-H743ZI2?qs=lYGu3FyN48cfUB5JhJTnlw%3D%3D).

## Network stack explained

### Network frame structure

When any two devices communicate, they exchange discrete pieces of data called

frames. Frames can be sent over the wire (like Ethernet) or over the air (like

WiFi or Cellular). Frames differ in size, and typically range from couple of

dozen bytes to a 1.5Kb. Each frame consists of a sequence of protocol headers

followed by user data:

The purpose of the headers is as follows:

**MAC (Media Access Control) header** is only 3 fields: destination MAC

address, source MAC addresses, and an upper level protocol. MAC addresses are

6-byte unique addresses of the network cards, e.g. `42:ef:15:c8:29:a1`.

Protocol is usually 0x800, which means that the next header is IP. MAC header

handles addressing in the local network (LAN).

**IP (Internet Protocol) header** has many fields, but the most important are:

destination IP address, source IP address, and upper level protocol. IP

addresses are 4-bytes, e.g. `209.85.202.102`, and they identify a machine

on the Internet, so their purpose is similar to phone numbers. The upper level

protocol is usually 6 (TCP) or 17 (UDP). IP header handles global addressing.

**TCP or UDP header** has many fields, but the most important are destination

port and source ports. On one device, there can be many network applications,

for example, many open tabs in a browser. Port number identifies

an application.

**Application protocol** depends on the target application. For example, there

are servers on the Internet that can tell an accurate current time. If you want

to send data to those servers, the application protocol must SNTP (Simple

Network Time Protocol). If you want to talk to a web server, the protocol must

be HTTP. There are other protocols, like DNS, MQTT, etc, each having their own

headers, followed by the application data.

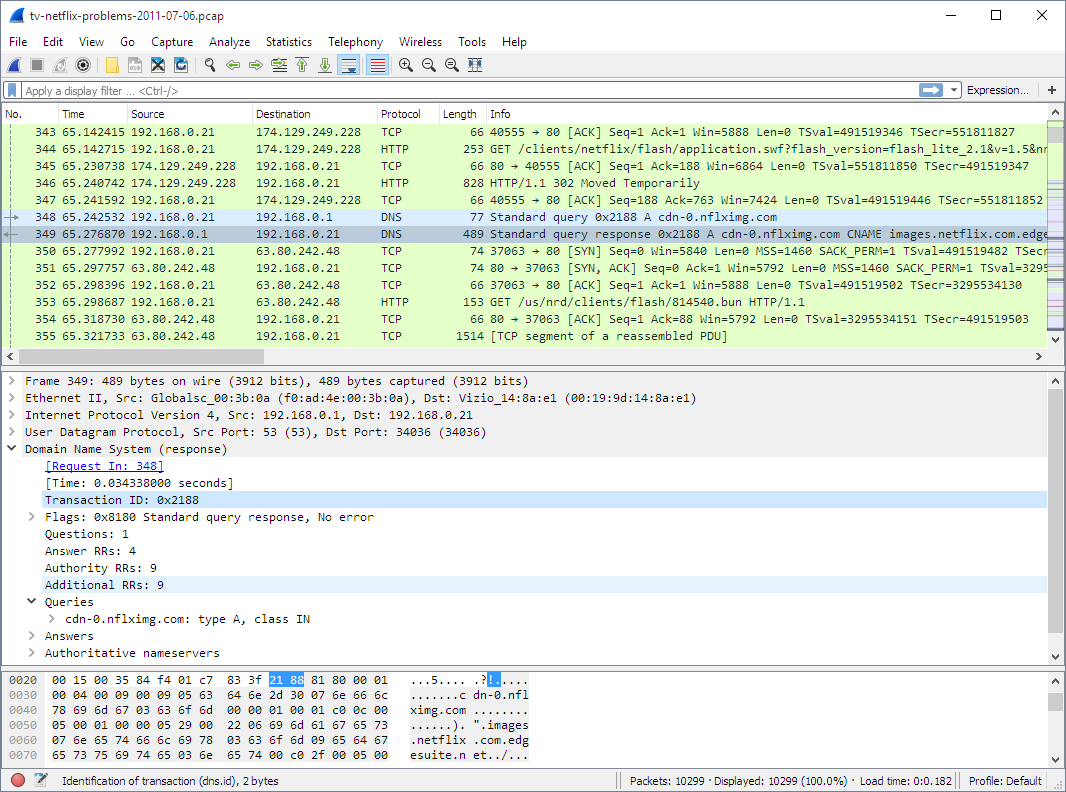

Install [Wireshark](https://www.wireshark.org/) tool to observe network

frames. It helps to identify issues quickly, and looks like this:

The structure of a frame described above, makes it possible to accurately

deliver a frame to the correct device and application over the Internet. When a

frame arrives to a device, a software that handles that frame (a network

stack), is organised in four layers.

### Network stack architecture

Layer 1: **Driver layer**, only reads and writes frames from/to network hardware

Layer 2: **TCP/IP stack**, parses protocol headers and handles IP and TCP/UDP

Layer 3: **Network Library**, parses application protocols like DNS, MQTT, HTTP

Layer 4: **Application** - Web dashboard, smart sensor, etc

### DNS request example

Let's provide an example. In order to show your this guide on the Github, your

browser first needs to find out the IP address of the Github's machine. For

that, it should make a DNS (Domain Name System) request to one of the DNS

servers. Here's how your browser and the network stack work for that case:

**1.** Your browser (an application) asks from the lower layer (library), "what

IP address `github.com` has?". The lower layer (layer 3, a library layer - in

this case, it is a C library) provides an API function `gethostbyname()`

that returns an IP address for a given host name. So everything said below,

essentially describes how `gethostbyname()` works.

**2.** The library layer gets the name `github.com` and creates a properly

formatted, binary DNS request: `struct dns_request`. Then it calls an API

function `sendto()` provided by the TCP/IP stack layer (layer 2), to send that

request over UDP to the DNS server. The IP of the DNS server is known to the library

from the workstation settings. The UDP port is also known - port 53, a standard

port for DNS.

**3.** The TCP/IP stack's `sendto()` function receives a chunk of data to send.

it contains DNS request, but `sendto()` does not know that and does not care

about that. All it knows is that this is the piece of user data that needs to

be delievered over UDP to a certain IP address (IP address of a DNS server) on

port 53. Hence TCP/IP stack prepends UDP, IP, and MAC headers

to the user data to form a frame. Then it calls API function `send_frame()`

provided by the driver layer, layer 1.

**4.** A driver's `send_frame()` function transmits a frame over the wire or

over the air, the frame travels to the destination DNS server. A chain of

Internet routers pass that frame from one to another, until a frame finally hits

DNS server's network card.

**5.** A network card on the DNS server gets a frame and generates a hardware

interrupt, invoking interrupt handler. It is part of a driver - layer 1. It

calls a function `recv_frame()` that reads a frame from the card, and passes

it up by calling `ethernet_input()` function provided by the TCP/IP stack

**6.** TCP/IP stack parses the frame, and finds out that it is for the UDP port

53, which is a DNS port number. TCP/IP stack finds an application that listens

on UDP port 53, which is a DNS server application, and wakes up its `recv()`

call. So, DNS server application that is blocked on a `recv()` call, receives

a chunk of data - which is a DNS request. A library routine parses that request

by extracting a host name, and passes that parsed DNS request to the application.

**7.** A DNS server application receives DNS request: "someone wants an

IP address for `github.com`". Then the application layer looks at its

configuration, figures out "Oh, it's me who is responsible for the github.com

domain, and this is the IP address I should respond with". The application

extracts an IP address from the configuration, and calls a library function

"get this IP, wrap into a DNS response, and send back". And the response

travels all the way back in the reverse order.

### BSD socket API

The communication between layers are done via a function calls. So, each

layer has its own API, which upper and lower levels can call. They are not

standardized, so each implementation provides their own set of functions.

However, on OSes like Windows/Mac/Linux/UNIX, a driver and TCP/IP layers are

implemented in kernel, and TCP/IP layer provides a standard API to the

userland which is called a "BSD socket API":

This is done becase kernel code does not implement application level protocols

like MQTT, HTTP, etc, - so it let's user application to implement them in

userland. So, a library layer and an application layer reside in userland.

Some library level routines are provided in C standard library, like

DNS resolution function `gethostbyname()`, but that DNS library functions

are probably the only ones that are provided by OS. For other protocols,

many libraries exist that provide HTTP, MQTT, Websocket, SSH, API. Some

applications don't use any external libraries: they use BSD socket API

directly and implement library layer manually. Usually that is done when

application decides to use some custom protocol.

Embedded systems very often use TCP/IP stacks that provide the same BSD API as

mainstream OSes do. For example, lwIP (LightWeight IP) TCP/IP stack, Keil's MDK

TCP/IP stack, Zephyr RTOS TCP/IP stack - all provide BSD socket API. Thus let's

review the most important BSD API stack functions:

- `socket(protocol)` - creates a connection descriptor and assigns an integer ID for it, a "socket"

- `bind(sock, addr)` - assigns a local IP:PORT for a listening socket

- `accept(sock, addr)` - creates a new socket, assigns local IP:PORT

and remote IP:PORT (incoming)

- `connect(sock, addr)` - assigns local IP:PORT and remote IP:PORT for

a socket (outgoing)

- `send(sock, buf, len)` - sends data

- `recv(sock, buf, len)` - receives data

- `close(sock)` - closes a socket

Some implementations do not implement BSD socket API, and there are perfectly

good reasons for that. Examples for such implementation is lwIP raw API,

and Mongoose Library.

### TCP echo server implemented with socket API

Let me demonstrate the two approaches (using socket and non-socket API) on a simple

TCP echo server example. TCP echo server is a simple application that

listens on a TCP port, receives data from clients that connect to that port,

and writes (echoes) that data back to the client. That means, this application

does not use any application protocol on top of TCP, thus it does not need

a library layer. Let's see how this application would look like written

with a BSD socket API. First, a TCP listener should bind to a port, and

for every connected client, spawn a new thread that would handle it. A thread

function that sends/receives data, looks something like this:

```c

void handle_new_connection(int sock) {

char buf[20];

for (;;) {

ssize_t len = recv(sock, buf, sizeof(buf), 0); // Receive data from remote

if (len <= 0) break; // Error! Exit the loop

send(sock, buf, len); // Success. Echo data back

}

close(sock); // Close socket, stop thread

}

```

Note that `recv()` function blocks until it receives some data from the client.

Then, `send()` also blocks until is sends requested data back to the client.

That means that this code cannot run in a bare metal implementation, because

`recv()` would block the whole firmware. For this to work, an RTOS is required.

A TCP/IP stack should run in a separate RTOS task, and both `send()` and

`recv()` functions are implemented using an RTOS queue API, providing a

blocking way to pass data from one task to another. Overall, this is how an

embedded receive path looks like with socket API:

The `send()` part would work in the reverse direction. Note that this approach

requires TCP/IP stack implement data buffering for each socket, because

an application consumes received data not immediately, but after some time,

when RTOS queue delivers data. Note that using non-blocking sockets and

`select()/poll()` changes things that instead of many application tasks,

there is only one application task, but the mechanism stays the same.

Therefore this approach with socket API has

the following major characteristics:

1. It uses queues for exchanging data between TCP/IP stack and

application tasks, which consumes both RAM and time

2. TCP/IP stack buffers received and sent data for each socket. Note that

the app/library layer may also buffer data - for example, buffering a full

HTTP request before it can be processed. So the same data goes through

two buffering "zones" - TCP/IP stack, and library/app

That means, socket API implementation takes extra time for data to be processed,

and takes extra RAM for double-buffering in the TCP/IP stack.

### TCP echo server with non-socket (callback) API

Now let's see how the same approach works without BSD socket API. Several

implementations, including lwIP and Mongoose Library, provide callback API to

the TCP/IP stack. Here is how TCP echo server would look like written using

Mongoose API:

```c

// This callback function is called for various network events, MG_EV_*

void event_handler(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data, void *fn_data) {

if (ev == MG_EV_READ) {

// MG_EV_READ means that new data got buffered in the c->recv buffer

mg_send(c, c->recv.buf, c->recv.len); // Send back the data we received

c->recv.len = 0; // Discard received data

}

}

```

In this case, all functions are non-blocking, that means that data exchange

between TCP/IP stack and an app can be implemented via direct function calls.

This is how receive path looks like:

As you can see, in this case TCP/IP stack provides a callback API which

a library or application layer can use to receive data directly. No need

to send it over a queue. A library/app layer can buffer data, and that's

the only place where buffering takes place. This approach wins for

memory usage and performance. A firmware developer should use

a proprietary callback API instead of BSD socket API.

lwIP TCP/IP stack, for example, provides both socket and non-socket (raw) API,

and raw API is more efficient in terms of RAM and performance. However

developers rarely use raw API, because it is not trivial to understand and use

compared to the socket API. The API of the Mongoose Library shown above

is designed to be simple and easy to understand. API design can make things

very easy or very difficult, so it is important to have a good API.

## Implementing layers 1,2,3 - making ping work

### Development environment and tools

Now let's make our hands dirty and implement a working network stack on

a microcontroller board. I will be using

[Mongoose Library](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose) for all examples

further on, for the following reasons:

- Mongoose is very easy to integrate: just by copying two files,

[mongoose.c]() and [mongoose.h]()

- Mongoose has a built-in drivers, TCP/IP stack, HTTP/MQTT/Websocket library,

and TLS 1.3 all in one, so it does not need any other software to create

a network-enabled application

- Mongoose provides a simple, polished callback API designed specifically

for embedded developers

The diagram below shows Mongoose architecture. As you can see, Mongoose can

use external TCP/IP stack and TLS libraries, as well as built-in ones. In the

following example, we are going to use only a built-in functionality, so we

won't need any other software.

All source code in this guide is MIT licensed, however Mongoose

is licensed under a dual GPLv2/commercial license.

I will be using a Nucleo board from ST Microelectronics, and there are several choices for the

development environment:

- Use Cube IDE provided by ST: [install Cube](https://www.st.com/en/development-tools/stm32cubeide.html)

- Use Keil from ARM: [install Keil](https://www.keil.com/)

- Use make + GCC compiler, no IDE: follow [this guide](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/tutorials/tools/)

Here, I am going to use Cube IDE. In the templates, however, both Keil and

make examples are provided, too. So, in order to proceed, install Cube IDE

on your workstation, and plug in Nucleo board to your workstation.

### Skeleton firmware

Note: this and the following sections has a Youtube helper video recorded:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKYM4b8TZts

The first step would be to create a minimal, skeleton firmware that does

nothing but logs messages to the serial console. Once we've done that, we'll

add networking functionality on top of it. The table below summarises

peripherals for various boards:

| Board | UART, TX, RX | Ethernet | LED |

| ---------------- | --------------- | ------------------------------------- | -------------- |

| STM32H747I-DISCO | USART1, A9, A10 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, G12, G11, G13 | I12, I13, I14 |

| STM32H573I-DK | USART1, A9, A10 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, G12, G11, G13 | I8, I9, F1 |

| Nucleo-H743ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, E1, B14 |

| Nucleo-H723ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, E1, B14 |

| Nucleo-H563ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B15, G11, G13 | B0, F4, G4 |

| Nucleo-F746ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

| Nucleo-F756ZG | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

| Nucleo-F429ZI | USART3, D8, D9 | A1, A2, A7, C1, C4, C5, B13, G11, G13 | B0, B7, B14 |

**Step 1.** Start Cube IDE. Choose File / New / STM32 project

**Step 2.** In the "part number" field, type the microcontroller name,

for example "H743ZI". That should narrow down

the MCU/MPU list selection in the bottom right corner to a single row.

Click on the row at the bottom right, then click on the Next button

**Step 3.** In the project name field, type any name, click Finish.

Answer "yes" if a pop-up dialog appears

**Step 4.** A configuration window appears. Click on Clock configuration tab.

Find a field with a system clock value. Type the maximum value, hit enter,

answer "yes" on auto-configuration question, wait until configured

**Step 5.** Switch to the Pinout tab, Connectivity, then enable the UART controller

and pins (see table above), choose "Asynchronous mode"

**Step 6.** Click on Connectivity / ETH, Choose Mode / RMII, verify that the

configured pins are like in the table above - if not, change pins

**Step 7.** Lookup the LED GPIO from the peripherals table, and configure it

for output. Click on the corresponding pin, select "GPIO output"

**Step 8.** Click Ctrl+S to save the configuration. This generates the code

and opens main.c file

**Step 9.** Navigate to the `main()` function and add some logging to the

`while` loop. Make sure to insert your code between the "USER CODE" comments,

because CubeIDE will preserve it during code regeneration:

```c

/* USER CODE BEGIN WHILE */

while (1)

{

printf("Tick: %lu\r\n", HAL_GetTick());

HAL_Delay(500);

```

**Step 10.** Redirect `printf()` to the UART. Note the UART global variable

generated by Cube at the beginning of `main.c` - typically it is

`UART_HandleTypeDef huart3;`. Copy it, open `syscalls.c`, find function

`_write()` and modify it the following way :

```c

#include "main.h"

__attribute__((weak)) int _write(int file, char *ptr, int len) {

if (file == 1 || file == 2) {

extern UART_HandleTypeDef huart3;

HAL_UART_Transmit(&huart3, (unsigned char *) ptr, len, 999);

}

return len;

}

```

**Step 11.** Click on "Run" button to flash this firmware to the board.

**Step 12.** Attach a serial monitor tool (e.g. putty on Windows, or

`cu -l COMPORT -s 115200` on Mac/Linux) and observe UART logs:

```

Tick: 90358

Tick: 90860

...

```

Our skeleton firmware is ready!

### Integrate Mongoose

Now it's time to implement a functional TCP/IP stack. We'll use Mongoose

Library for that. To integrate it, we need to copy two files into our source tree.

**Step 1**. Open https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose in your browser, click on "mongoose.h". Click on "Raw" button, and copy file contents into clipboard.

In the CubeIDE, right click on Core/Inc, choose New/File in the menu, type

"mongoose.h", paste the file content and save.

**Step 2**. Repeat for "mongoose.c". On Github, copy `mongoose.c` contents

to the clipboard. In the CubeIDE, right click on Core/Src, choose New/File

in the menu, type "mongoose.c", paste the file content and save.

**Step 3**. Right click on Core/Inc, choose New/File in the menu, type

"mongoose_custom.h", and paste the following contents:

```c

#pragma once

// See https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#build-options

#define MG_ARCH MG_ARCH_NEWLIB

#define MG_ENABLE_TCPIP 1 // Enables built-in TCP/IP stack

#define MG_ENABLE_CUSTOM_MILLIS 1 // We must implement mg_millis()

#define MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32H 1 // On STM32Fxx series, use MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32F

```

**Step 4**. Implement Layer 1 (driver), 2 (TCP/IP stack) and 3 (library) in

our code. Open `main.c`. Add `#include "mongoose.h"` at the top:

```c

/* USER CODE BEGIN Includes */

#include "mongoose.h"

/* USER CODE END Includes */

```

**Step 5**. Before `main()`, define function `mg_millis()` that returns

an uptime in milliseconds. It will be used by Mongoose Library for the time

keeping:

```c

/* USER CODE BEGIN 0 */

uint64_t mg_millis(void) {

return HAL_GetTick();

}

/* USER CODE END 0 */

```

**Step 6**. Navigate to `main()` function and change the code around `while`

loop this way:

```c

/* USER CODE BEGIN WHILE */

struct mg_mgr mgr;

mg_mgr_init(&mgr);

mg_log_set(MG_LL_DEBUG);

// On STM32Fxx, use _stm32f suffix instead of _stm32h

struct mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h_data driver_data = {.mdc_cr = 4};

struct mg_tcpip_if mif = {.mac = {2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7},

// Uncomment below for static configuration:

// .ip = mg_htonl(MG_U32(192, 168, 0, 223)),

// .mask = mg_htonl(MG_U32(255, 255, 255, 0)),

// .gw = mg_htonl(MG_U32(192, 168, 0, 1)),

.driver = &mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h,

.driver_data = &driver_data};

NVIC_EnableIRQ(ETH_IRQn);

mg_tcpip_init(&mgr, &mif);

while (1) {

mg_mgr_poll(&mgr, 0);

/* USER CODE END WHILE */

```

**Step 7**. Connect your board to the Ethernet. Flash firmware. In the serial

log, you should see something like this:

```

bb8 3 mongoose.c:14914:mg_tcpip_driv Link is 100M full-duplex

bbd 1 mongoose.c:4676:onstatechange Link up

bc2 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

c0e 3 mongoose.c:4755:tx_dhcp_reques DHCP req sent

c13 2 mongoose.c:4882:rx_dhcp_client Lease: 86400 sec (86403)

c19 2 mongoose.c:4671:onstatechange READY, IP: 192.168.2.76

c1e 2 mongoose.c:4672:onstatechange GW: 192.168.2.1

c24 2 mongoose.c:4673:onstatechange MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

```

If you don't, and see DHCP requests message like this:

```

130b0 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

13498 3 mongoose.c:4776:tx_dhcp_discov DHCP discover sent. Our MAC: 02:03:04:05:06:07

...

```

The most common cause for this is you have your Ethernet pins wrong. Click

on the `.ioc` file, go to the Ethernet configuration, and double-check the

Ethernet pins against the table above.

**Step 8**. Open terminal/command prompt, and run a `ping` command against

the IP address of your board:

```sh

$ ping 192.168.2.76

PING 192.168.2.76 (192.168.2.76): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 192.168.2.76: icmp_seq=0 ttl=64 time=9.515 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.2.76: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=1.012 ms

```

Now, we have a functional network stack running on our board. Layers 1,2,3

are implemented. It's time to create an application - a simple web server,

hence implement layer 4.

## Implementing layer 4 - a simple web server

Let's add a very simple web server that responds "ok" to any HTTP request.

**Step 1**. After the `mg_tcpip_init()` call, add this line that creates HTTP listener

with `fn` event handler function:

```c

mg_http_listen(&mgr, "http://0.0.0.0:80", fn, NULL);

```

**Step 2**. Before the `mg_millis()` function, add the `fn` event handler function:

```c

static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

struct mg_http_message *hm = ev_data; // Parsed HTTP request

mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "ok\r\n");

}

}

```

That's it! Flash the firmware. Open your browser, type board's IP address and

see the "ok" message.

Note that the [mg_http_reply()](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#mg_http_reply)

function is very versatile: it cat create formatted output, like printf

on steroids. See [mg_snprintf()](https://mongoose.ws/documentation/#mg_snprintf-mg_vsnprintf)

for the supported format specifiers: most of them are standard printf, but

there are two non-standard: `%m` and `%M` that accept custom formatting

function - and this way, Mongoose's printf can print virtually anything.

For example, JSON strings. That said, with the aid of `mg_http_reply()`,

we can generate HTTP responses of arbitrary complexity.

So, how the whole flow works? Here is how. When a browser connects,

an Ethernet IRQ handler (layer 1) kicks in. It is defined by Mongoose, and activated by

the `#define MG_ENABLE_DRIVER_STM32H 1` line in the `mongoose_custom.h`: [ETH_IRQHandler](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/drivers/stm32h.c#L252). Other environments, like CubeIDE, implement `ETH_IRQHandler`

and activate it when you select "Enable Ethernet interrupt" in the Ethernet

configuration. To avoid clash with Cube, we did not activate Ethernet interrupt.

IRQ handler reads frame from the DMA, copies that frame to the Mongoose's

[receive queue](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.h#L30), and exits.

That receive queue is special, it is a thread-safe

single-producer-single-consumer non-blocking queue, so an IRQ handler, being

executed in any context, can safely write to it.

The `mg_poll()` function in the infinite `while()` loop constantly

verifies, whether we receive any data in the receive queue. When it detects

a frame in the receive queue, it extracts that frame, passes it on to the

[mg_tcp_rx()](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L800) function - which is an etry point to the layer 2 TCP/IP stack.

That `mg_tcp_rx()` function parses headers, starting from Ethernet header,

and when it detects that a received frame belongs to one of the Mongoose

TCP or UDP connections, it copies frame payload to the connection's `c->recv`

buffer and [calls `MG_EV_READ` event](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L687).

At this point, processing leaves layer 2 and enters layer 3 - a library layer.

Mongoose's HTTP event handlers catches `MG_EV_READ`, parses received data,

and when it detects that the full HTTP message is buffered, it [sends the

`MG_EV_HTTP_MSG` with parsed HTTP message](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/http.c#L1033) to the application - layer 4.

And this is where our event handler function `fn()` gets called. Our code is

simple - we catch `MG_EV_HTTP_MSG` event, and use Mongoose's API function

`mg_http_reply()` to craft a simple HTTP response:

```

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Length: 4

ok

```

This response goes to Mongoose's `c->send` output buffer, and `mg_mgr_poll()`

drains that data to the browser, [splitting the response by frames](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/net_builtin.c#L587-L588)

in layer 2, then passing to the layer 1. An Ethernet driver's output function [mg_tcpip_driver_stm32h_tx()](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/68e2cd9b296733c9aea8b3401ab946dd25de9c0e/src/drivers/stm32h.c#L208) sends those frames back to the browser.

This is how Mongoose Library works.

Other implementations, like Zephyr, Amazon FreeRTOS-TCP, Azure, lwIP, work in

a similar way. They implement BSD socket layer so it is a bit more complicated

cause it includes an extra socket layer, but the principle is the same.

## Implementing Web UI

Using `mg_http_reply()` function is nice, but it's very good for creating

custom responses. It is not suitable for serving files. And the standard way

to build a web UI is to split it into two parts:

- a static part, which consists of directory with `index.html`, CSS,

JavaScript and image files,

- a dynamic part, which serves REST API

So instead of using `mg_http_reply()` and responding with "ok" to any request,

let's create a directory with `index.html` file and serve that directory.

Mongoose has API function `mg_http_serve_dir()` for that. Let's change the

event handler code to use that function:

```c

static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

struct mg_http_message *hm = ev_data; // Parsed HTTP request

struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root"};

mg_http_serve_dir(c, hm, &opts);

}

}

```

Build it and get build error "undefined reference to 'mkdir'". This is because

`mg_http_serve_dir()` function tries to use a default POSIX filesystem to

read files from directory `/web_root`, and our firmware does not have support

for the POSIX filesystem.

What are the possibilities here? First, we can implement POSIX filesystem,

by using an internal or external flash memory. Then we can copy our `web_root`

directory there, and our code will start to work. This is the hard way.

The easy way is to use a so-called embedded filesystem, by

transforming all files in the web directory into C arrays, and compiling them

into the firmware binary. This way, all UI files are simply hardcoded into the

firmware binary, and there is no need to implement a "real" filesystem:

**Step 1**. Tell `mg_http_serve_dir()` to use packed filesystem:

```c

struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root", .fs = &mg_fs_packed};

```

**Step 2**. Enable packed filesystem, and disable POSIX filesystem in `mongoose_custom.h`:

```c

#define MG_ENABLE_PACKED_FS 1

#define MG_ENABLE_POSIX_FS 0

```

**Step 3**. Create a new file `Core/Src/packed_fs.c`. Go to https://mongoose.ws/ui-pack/,

review UI files. Copy/paste the contents of generated `packed_fs.c`, save.

Build the firmware - and now it should build with no errors.

Let's review what that UI packer does. As you can see, it has 3 files, which

implement a very simple Web UI with LED control. The `index.html` file

loads `main.js` file, which defines a button click handler. When a button

gets clicked, it makes a request to the `api/led/toggle` URL, and when

than request completes, it makes another request to `api/led/get` URL,

and sets the status span element to the result of the request.

The tool has a preview window, and if any of the files are changed,

it automatically refreshes preview and regenerates packed_fs.c. The packed_fs.c

is a simple C file, which contains three C arrays, representing three files

we have, and two helper functions `mg_unlist()` and `mg_unpack()`, used by

Mongoose:

- the `mg_unlist()` function allows to scan the whole "filesystem" and get names of every file,

- the `mg_unpack()` function returns file contents, size, and modification time for a given file.

Mongoose provides a command line utility [pack.c](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/master/test/pack.c)

to generate `packed_fs.c` automatically during the build. The example of that

is a [Makefile](https://github.com/cesanta/mongoose/blob/f883504d2d44d24cae1ca6c9f88ce780ab36f59b/examples/device-dashboard/Makefile#L38-L43)

for device dashboard example in Mongoose repository, which not only packs,

but also compresses files to minimise their size. But here, we'll use the

web tool because it is visual and makes it easy to understand the flow.

The static HTML is extremely simple. There 3 files: `index.html`, `style.css`

and `main.js`. The `index.html` references, or loads, the other two:

**index.html:**

```html

My Device

LED status:

0

Toggle LED

```

**style.css:**

```css

.main { margin: 1em; }

#status { display: inline-block; width: 2em; }

```

The Javascript code in the `main.js` file installs an event handler on button

click, so when a user clicks on a button, JS code makes HTTP requests -

I'll comment down below how it all works together:

**main.js:**

```javascript

var getStatus = ev => fetch('api/led/get')

.then(r => r.json())

.then(r => { document.getElementById('status').innerHTML = r; });

var toggle = ev => fetch('api/led/toggle')

.then(r => getStatus());

document.getElementById('btn').onclick = toggle;

```

Now, let's flash the firmware. Go to the IP address in the browser - and

now we see the Web UI with a button! Click on the button, and see that nothing

happens! The LED does not turn on and off. Open developer tools and see that

on every click, a browser makes "toggle" and "get" requests which return 404

error - not found. Let's implement those API calls.

Change the event handler in the following way:

```c

static void fn(struct mg_connection *c, int ev, void *ev_data) {

if (ev == MG_EV_HTTP_MSG) {

struct mg_http_message *hm = (struct mg_http_message *) ev_data;

if (mg_http_match_uri(hm, "/api/led/get")) {

mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "%d\n", HAL_GPIO_ReadPin(GPIOB, GPIO_PIN_0));

} else if (mg_http_match_uri(hm, "/api/led/toggle")) {

HAL_GPIO_TogglePin(GPIOB, GPIO_PIN_0); // Can be different on your board

mg_http_reply(c, 200, "", "true\n");

} else {

struct mg_http_serve_opts opts = {.root_dir = "/web_root", .fs = &mg_fs_packed};

mg_http_serve_dir(c, hm, &opts);

}

}

}

```

Note the `mg_http_match_uri()` checks. There, we are making different responses

to different URLs. On `/api/led/get` URL request, we're responding with

LED status, and on `/api/led/toggle` request, we're toggling the pin and

responding with `true`.

Build and flash this firmware. Refresh the page in the browser. Click on the

button - and now, LED toggle works! If we open developer tools in the browser,

we can see the sequence of the network requests made by the browser.

Below is the diagram of the interaction between the browser and the device,

with explanations of every step:

This is the flow for the Web UI of any complexity. Now, it is just a matter of

creating a professional UI interface using any suitable JS/CSS framework, and

extending the event handler function with the API calls that that UI invokes.

That's all it takes.

## Implementing Device Dashboard

Let me show you how to repeat everything we did in Cube - in the make + GCC

environment in one minute. Navigate to https://mongoose.ws/demo/?clear=1

This simple web tool creates a make project completely in your browser.

Choose the board, the "simple project". You can download the project to your

workstation and build manually. But we'll build in a browser - click on Build

button. That zips the projects and sends it to mongoose.ws site, which has

ARM GCC pre-installed. It simply runs `make`, creates firmware binary, and

sends that binary back to your browser. Now you can download that binary,

or flash it directly from your browser.

The "simple" project repeats what we've already done in Cube, with one

important difference - it also implements TLS. In other words, it can serve

both HTTP and HTTPS. Note that the binary size is less than 60 Kb! We will

cover TLS later, as it needs a separate discussion.

Now, let's click on "Start Over" button and build "Web UI Dashboard" project.

It follows absolutely the same flow as "simple" project, just the Web UI is

significantly more versatile, built with Preact JS framework and Tailwind CSS

framework. The event handler function moved into a separate file, `net.c`,

and supports many API calls required by Web UI - to show dashboard stats,

settings, and firmware update. By the way, the firmware update is completely

functional - but I won't cover it here, as it is a big topic on itself.

I won't cover the process of static UI creation in React, as there are tons

of very good tutorials on that. But if you want me to cover that, join our

Discord server and let me know.

What I'll do is to move that UI into the Cube project of ours.

**Step 1.** Copy net.c, net.h, packed_fs.c into the Cube project

**Step 2.** Add the following `include "net.h"` at the top of the main.c file

**Step 3.** Comment out `mg_http_listen(...)` call, add `web_init()` call

**Step 4.** Open net.h, modify HTTP_URL port 8000 to port 80

Rebuild, reflash, refresh your browser. We have a functional versatile

Web UI device dashboard reference running!

## Device management using MQTT protocol

## Enabling TLS

## Talking to AWS IoT and Microsoft Azure services

## About me

I am Sergey Lyubka, an engineer and entrepreneur. I hold a MSc in Physics from

Kyiv State University, Ukraine. I am a director and a co-founder at Cesanta - a

technology company based in Dublin, Ireland. Cesanta develops embedded

solutions:

- https://mongoose.ws - an open source HTTP/MQTT/Websocket network library

- https://vcon.io - a remote firmware update / serial monitor framework

You are welcome to register for

[my free webinar on embedded network programming](https://mongoose.ws/webinars/)