https://github.com/funkia/turbine

Purely functional frontend framework for building web applications

https://github.com/funkia/turbine

framework frp functional-reactive-programming javascript pure typescript

Last synced: 9 months ago

JSON representation

Purely functional frontend framework for building web applications

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/funkia/turbine

- Owner: funkia

- License: mit

- Created: 2016-09-02T12:23:51.000Z (over 9 years ago)

- Default Branch: master

- Last Pushed: 2023-01-07T02:23:08.000Z (about 3 years ago)

- Last Synced: 2025-04-12T14:56:32.208Z (10 months ago)

- Topics: framework, frp, functional-reactive-programming, javascript, pure, typescript

- Language: TypeScript

- Homepage:

- Size: 4.5 MB

- Stars: 688

- Watchers: 24

- Forks: 27

- Open Issues: 64

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

# Turbine

A purely functional frontend framework based on functional reactive

programming. Experimental.

[](https://gitter.im/funkia/General)

[](https://travis-ci.org/funkia/turbine)

[](https://codecov.io/gh/funkia/turbine)

# Table of contents

- [Why Turbine?](#why-turbine)

- [Examples](#examples)

- [High-level overview](#high-level-overview)

- [Principles](#principles)

- [Installation](#installation)

- [More examples](#more-examples)

- [Tutorial](#tutorial)

- [API](#api)

- [Contributing](#contributing)

## Why Turbine?

The JavaScript world is full of frameworks. So why another one?

Because we want something _different_. We want something that is

purely functional without compromises. Something that takes the best

lessons from existing JavaScript frameworks and couples them with the

powerful techniques found in functional languages like Haskell. We

want a framework that is highly expressive. Because when functional

programming is at its best it gives you more power, not less. Turbine

is supposed to be approachable for typical JavaScript developers while

still preserving the benefits that comes from embracing purely

functional programming.

We have done our best to realize our goal. But we are not done yet. We

hope you will find Turbine interesting, try it and maybe even help us

making it even better.

## Examples

### Email validator

[See the example live and editable here.](https://codesandbox.io/s/xenodochial-williams-xok6q)

```js

const isValidEmail = (s: string) => /.+@.+\..+/i.test(s);

const app = component((on) => {

const isValid = on.email.map(isValidEmail);

return [

span("Please enter an email address: "),

input().use({ email: "value" }),

div(["The address is ", isValid.map((b) => (b ? "valid" : "invalid"))])

];

});

// `runComponent` is the only impure function in application code

runComponent("#mount", main);

```

### Counter

[See the example live and editable here.](https://codesandbox.io/s/pedantic-frog-beisw)

```js

const counter = component((on, start) => {

const count = start(accum((n, m) => n + m, 0, on.delta));

return E.div([

"Counter ",

count,

E.button({ class: "btn btn-default" }, " + ").use(o => ({

delta: o.click.mapTo(1)

})),

E.button({ class: "btn btn-default" }, " - ").use(o => ({

delta: o.click.mapTo(-1)

}))

]);

});

// `runComponent` is the only impure function in application code

runComponent("#mount", counter);

```

[See more examples here](#more-examples).

## High-level overview

Here our some of our key features.

- Purely functional. A Turbine app is made up of only pure functions.

- Leverage TypeScript and runtime checking to improve the developing

experience.

- Based on classic FRP. Behaviors represents values that change over

time and streams provide reactivity. Turbine uses the FRP

library [Hareactive](https://github.com/funkia/hareactive).

- A component-based architecture. Components are immutable,

encapsulated and composable. Components are monads and are typically

used and composed with do-notation (we implement do-notation with

generators).

- Constructed DOM elements reacts directly to behaviors and streams.

This avoids the overhead of using virtual DOM and should lead to

great performance.

- Side-effects are expressed with a declarative IO monad. This allows

for easy testing of code with side-effects. Furthermore, the

IO-monad is integrated with FRP.

- The entire data flow through applications is explicit and easy to

follow.

- Our libraries are available both as CommonJS and ES2015 modules.

This allows for tree-shaking.

Here are some of the features we want to implement and goals we're

working towards.

- Declarative and concise testing of time-dependent FRP code.

- Performance. We think Turbine can be made very efficient. But we are

not yet at a point where we focus on performance.

- Support for server side rendering.

- Browser devtools for easier development and debugging.

- Hot-module replacement (if possible given our design).

## Principles

This section describes some of the key principles and ideas underlying

the design of Turbine.

### Purely functional

Turbine is purely functional. We mean that in the most strict sense of

the term. In a Turbine app, every single expression is pure. This

gives a huge benefit in how easy it is to understand and maintain a

Turbine app is.

One benefit of the complete purity is that every function in Turbine

supports what is called "referential transparency". This means that an

expression can always be replaced with its value.

As a simple example, say you have the following code:

```js

const view = div([

myComponent({ foo: "bar", something: 12 }),

myComponent({ foo: "bar", something: 12 })

]);

```

One may notice that `myComponent` is called twice with the exact same

arguments. Since all functions in a Turbine app are pure `myComponent`

is no exception. Hence, we can make the following simple refactoring.

```js

const component = myComponent({foo: "bar", something: 12}),

const view = div([

component,

component

]);

```

Such refactorings can always be safely done in Turbine.

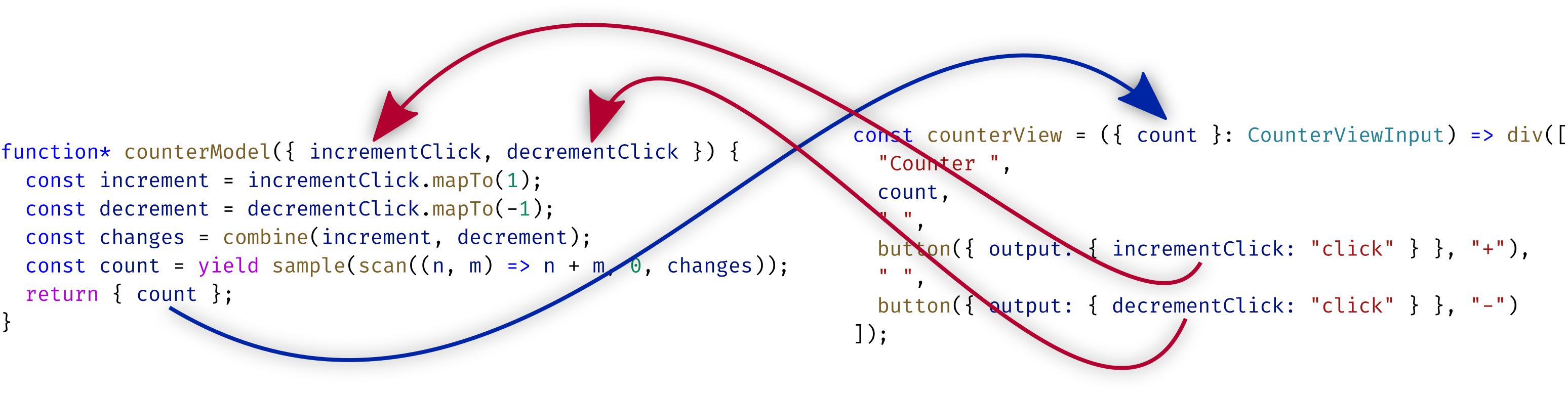

### Completely explicit data flow

One significant challenge when writing an interactive frontend

application is how to manage the data flow through an application.

In Turbine we have strived to create an architecture where the data

flow is easy to follow and understand. For us, this means that when

looking at any piece of code it should be possible to see what other

parts of the application it affects and what other parts it is

affected by.

One manifestation of this principle is that in Turbine it is very

simple to see how the model affects the view and how the view affects

the model. The figure below illustrates this.

The arrows represent data flow between the model and the view. Note

how these "conceptual arrows" are clearly expressed in the code. For

instance, by looking at the buttons we can see exactly what output

they produce.

### Declarative models

Imperative programming is about _doing_. Functional programming is

about _being_. This mean that ideally a functional program should be

about defining what things are. That property is what makes functional

programs declarative.

Below is a model from the [counters example](/examples/counters).

Notice how the model consists of nothing but a series of `const`

statements.

```js

function* counterModel({ incrementClick, decrementClick, deleteClick }) {

const increment = incrementClick.mapTo(1);

const decrement = decrementClick.mapTo(-1);

const deleteS = deleteClick.mapTo(id);

const count = yield accum(add, 0, combine(increment, decrement));

return { count, deleteS };

}

```

Each line is a declaration of a piece of the state. All models in

Turbine follows this pattern. This makes state in a Turbine app very

easy to understand. One can look at a single definition and be certain

that it tells everything there is to know about that specific piece of

state.

This is in sharp contrast to frameworks that mutate state or

frameworks where state is stepped forward by reducer functions. With

such approaches a single piece of state can potentially be affected

and changed in several places. That can make it hard to understand how

the state evolves. The benefits of having a definition as a

single source of truth is lost.

## Installation

```sh

npm install @funkia/turbine @funkia/hareactive

```

[Hareactive](https://github.com/funkia/hareactive) is a peer

dependency. It is the FRP library that that Turbine is based upon.

Alternatively, for quickly trying out Turbine you may want to see our

[Turbine starter kit](https://github.com/funkia/turbine-starter).

## More examples

Here is a series of examples that demonstrate how to use Turbine.

Approximately listed in order of increasing complexity.

- [Email validator](/examples/email-validator) — Very simple example of an email

validator.

- [Fahrenheit celsius](/examples/fahrenheit-celsius) — A converter

between fahrenheit and celsius.

- [Zip codes](/examples/zip-codes) — A zip code validator. Shows one

way of doing HTTP-requests with the IO-monad.

- [Continuous time](/examples/continuous-time) — Shows how to utilize

continuous time.

- [Counters](/examples/counters) — A list of counters. Demonstrates

nested components, managing a list of components and how child

components can communicate with parent components.

- [Todo](/examples/todo) — An implementation of the classic

TodoMVC application.

## Tutorial

In this tutorial, we will build a simple application with a list of

counters. The application will be simple but not completely trivial.

Along the way, most of the key concepts in Turbine will be explained.

We will see how to create HTML, how to create custom components, how a

component can be nested and how it can share state with its parent.

Please open an issue if you have questions regarding the tutorial or

ideas for improvements.

The final result and the intermediate states can be seen by cloning

this git repository, going into the directory with the counters

example and running webpack to serve the application.

```

git clone https://github.com/funkia/turbine/

cd turbine/examples/counters

npm run start

```

### FRP

Turbine builds on top of the FRP library Hareactive. The two key

concepts from FRP are _behavior_ and _stream_. They are documented in

more detail in the [Hareactive

readme](https://github.com/funkia/hareactive). But the most important

things to understand are behavior and stream.

- `Behavior` represents values that change over time. For instance,

the position of the mouse or the number of times a user has clicked

a button.

- `Stream` represents discrete events that happen over time. For

instance click events.

### What is `Component`

On top of the FRP primitives Turbine adds `Component`. Component is the

key concept in Turbine. Once you understand `Component`—and how to use

it—you understand Turbine. A Turbine app is just one big component.

Here is a high-level overview of what a component is.

- Components can **contain logic** expressed through operations on

behaviors and streams.

- Components are **encapsulated** and have completely private state.

- Components **contain output** through which they selectively decide

what state they share with their parent.

- Components **write DOM elements** as children to their parent. They

can write zero, one or more DOM elements.

- Components can **declare side-effects** expressed as `IO`-actions.

- Components are **composable**—one component can be combined with

another component and the result is a third component.

A `Component` in Turbine is pure and immutable. A `Component` can be

thought of as a huge description of all of the above mentioned things.

For instance, a `Component` contains a description about what its DOM

look like. That part is a bit like virtual DOM. But, on top op that

the description also explain how the DOM changes over time. The

description also tells what output the `Component` contains. More on

that later.

### Creating HTML-elements

Turbine includes functions for creating components that represent

standard HTML-elements. When you create your own components they will

be made of these.

The element functions accept two arguments, both of which are

optional. The first is an object describing various things like

attributes, classes, etc. The second argument is a child component.

For instance, to create a div with a span child we would write.

```typescript

const myDiv = div({ class: "foo" }, span("Some text"));

```

The element functions are overloaded. So instead of giving `span` a

component as child we can give it a string. The element functions also

accept an array of child elements like this.

```typescript

const myDiv = div({ class: "foo" }, [h1("A header"), p("Some text")]);

```

Using this we can build arbitrarily complex HTML. As an example we

will build a simple view for a counter in our counter-application.

```ts

import { elements, runComponent } from "@funkia/turbine";

const { br, div, button } = elements;

// Counter

const counterView = div(["Counter ", 1, " ", button("+"), " ", button("-")]);

runComponent("body", counterView);

```

We define `counterView` as div-element with some text and two buttons

inside. Since `div` returns a component `counterView` is a component.

And a Turbine application is just a component so we have a complete

application. We run the application on the last line when we call

`runComponent`. It is an impure function that takes a selector, a

component and runs the component with the found element as parent. You

can view the entire code in `version1.ts`.

### Dynamic HTML

The `counterView` above is completely static. The buttons do nothing

and we hard-coded the value `1` into the view. Our next task is to

make the program interactive.

Anywhere where we can give the element functions a constant value of a

certain type we can alternatively give them a behavior with a value of

that type. For instance, if we have a string-valued behavior we can

use it like this

```ts

const mySpan = span(stringBehavior);

```

This will construct a component representing a span element with text

content that is kept up to date with the value of the behavior.

To make the count in our counter view dynamic we turn it into a

function that takes a behavior of a number and inserts it into the

view.

```ts

const counterView = ({ count }: CounterViewInput) =>

div(["Counter ", count, " ", button("+"), " ", button("-")]);

```

Because it will be easier going forward `counterView` takes an object

with a `count` property.

### Output from components

The above covers the _input_ to the counter view. We now need to get

_output_ from it.

Remember that we mentioned how a Turbine component is a description

about what the component will behave and look like. Part of that

description also explains what output will come from the component.

To get a feel for what "output" means it may be helpful to mention a

few examples.

- A button outputs, among other things, a stream of click events. So

part of its output is a stream of the type `Stream>`.

- An input box's output includes a behavior of the text inside the

input. The type would be `Behavior`.

- A checkbox might output a behavior representing whether it is

checked or not. It would have type `Behavior`.

One way of looking at the output is that it is the information we

would like to get from the view.

In practice a component will almost always output more than a single

stream or behavior. By convention the output is therefore almost alway

an object.

Components are represented by a generic type `Component`. The

`A` represents the _available_ output of the component and the `O`

represents the _selected_ out of the component. The difference

between selected and available output is highlighted in the example

below.

Constructing an input element looks like this

```ts

const usernameInput = input({ placeholder: "Username" });

```

The type of the component constructed above is as follows ( the `...`

refer to the fact that we have omitted a lot of the output to keep

things simple).

```ts

Component<{}, { value: Behavior, click: Stream, ... }>

```

Among its available output an `input` element produces a string valued

behavior named `value` that contains the current content of the

`input` element.

Like this input component a newly constructed component always have

`{}` as its selected output. This means that initially no output is

selected. We can move output from the available output into the

selected output by using the `output` method on components.

```ts

const usernameInput = input({

attrs: { placeholder: "Username" }

}).output({ username: "value" });

```

Here `usernameInput` has the type

```ts

Component<{ username: Behavior }, ...>

```

In the above code the invocation to `output` means: from the object of

available output take the `value` property and add it to the object of

selected output with the property name `username`.

The difference between available output and selected output matters

when components are combined. In most cases, when components are

composed or combined all their available output is discarded and only

the selected output becomes part of the combined component.

For instance, in the code below the `div` is given two children.

```ts

div([

button("Click me").output({ firstButtonClick: "click" }),

button("Don't click me")

]);

```

The `div` element composes the two buttons. When doing so all output

from the buttons except for the `click` stream from the first button

is discarded.

Using the `output` method is a bit like adding event handlers in other

UI frameworks. There are many events that one can add handlers to but

on any given element only a few events are actually of interest and

for these one will add event handlers. Similarly, in Turbine

components have a lot of available output but only the piece of it

that gets selected will be output in the end.

Back to the counters app. We want our counter view to produce two

streams as output. One stream should be from whenever the first button

is clicked and the other stream should contain clicks from the second

button. That is, the view's output should have the type

```ts

{

incrementClick: Stream,

decrementClick: Stream

}

```

We can achieve that by using the `output` method in each button.

```ts

const counterView = ({ count }) =>

div([

"Counter ",

count,

" ",

button("+").output({ incrementClick: "click" }),

" ",

button("-").output({ decrementClick: "click" })

]);

```

The call to `output` on each `button` tells them what output we are

interested in. The first buttons selected output is then object with a

stream named `incrementClick` and the later and object with one named

`decrementClick`.

The `div` function then combines the selected output from the

components in the array passed to it and output that as its own

selected output. The result is that `counterView` returns a component

that produces two streams as its output.

### An analogy with promises

As mentioned above using the `output` method is a bit like adding

event listeners in other frameworks. However, there are fundamental

differences between the two things. If you are familiar with how

asynchronous functions that takes callbacks differ from asynchronous

function that returns promises then the following analogy may help

understand this difference.

An asynchronous function for reading a file may look like this

```js

readFileCallback("foo.txt", (file) => ...)

```

A similar function based on promises looks like

this.

```js

readFilePromise("foo.txt").then((file) => ...)

```

Notice that the `readFileCallback` function does not return the file

that it reads. The file is instead passed to a callback that it gets

as an argument. The `readFilePromise` function on the other hand

returns the file wrapped in a promise of the type `Promise`.

Most UI frameworks are similar to the `readFileCallback` function. In

order to know when a button is pressed you do something like this.

```tsx

...}>Click me

```

The click events on the button are not returned from the `button`

function. Instead they are passed to a callback (or event handler)

that the `button` function gets as an argumen.

The same thing in Turbine looks like this.

```ts

button("Click me").output({ click: "click" });

```

This is similar to the `readFilePromise` function. The `button`

function does not take any callbacks but returns a stream of clicks

wrapped in a component of the type `Component<{ click: Stream }, ...>`.

This example should give some intuition about how Turbine differs from

most other frameworks. Other frameworks handle events similar to doing

asynchronous computations with callbacks but Turbine handle events

similarly to doing asynchronous computations with promises. In

particular when creating components the output is _returned_ as part

of the component.

### Adding a model

We now need to add a model with some logic to our counter view. The

model needs to handle the increment and decrement stream and turn them

into a behavior that represents the current count.

Turbine offers the function `modelView` for creating components with

logic. `modelView` takes two arguments. The first describes the logic

and the second the view. This keeps the logic neatly separated from

the view.

The second argument to `modelView`, the view, is a function that

returns a component. We already have such a function: `counterView`.

The first argument is a function that returns a `Now`-computation. You

don't have to fully understand `Now`. One of the things it does is to

make it possible to create stateful behaviors. The model function will

as input receive the output from the component that the view function

returns. The result of the `Now`-computation will be passed on to the

view function and will be the output of the component that `modelView`

returns. Here is how we use to create our counter component.

```ts

function* counterModel({ incrementClick, decrementClick }: CounterModelInput) {

const increment = incrementClick.mapTo(1);

const decrement = decrementClick.mapTo(-1);

const changes = combine(increment, decrement);

const count = yield accum((n, m) => n + m, 0, changes);

return { count };

}

const counter = modelView(counterModel, counterView)();

```

Note that there is a cyclic dependency between the model and the view.

The figure below illustrates this.

We now have a fully functional counter. You have now seen how to

create a simple component with encapsulated state and logic. The

current code can be seen in `version2.ts`.

### Creating a list of counters

Our next step is to create a list of counters. To do that we will

create a new component called `counterList`. The component will

contain a list of `counter` components as well as a button for adding

counters to the list.

Let's begin by defining a view function that creates a header and a

button.

```js

function* counterListView() {

yield h1("Counters");

const { click: addCounter } = yield button(

{ class: "btn btn-primary" },

"Add counter"

);

return { addCounter };

}

```

We hook the view up to a model using `modelView`. Again, the model

function receives the return value from the view function.

```js

const counterList = modelView(counterListModel, counterListView);

const counterListModel = fgo(function*({ addCounter, listOut }) {

const nextId = yield scan(add, 2, addCounter.mapTo(1));

const appendCounterFn = map(

(id) => (ids: number[]) => ids.concat([id]),

nextId

);

const counterIds = yield accum(apply, [0], appendCounterFn);

return { counterIds };

});

const counterListView = ({ sum, counterIds }) => [

h1("Counters"),

button({ class: "btn btn-primary" }, "Add counter").output({

addCounter: "click"

}),

ul(list(counter, counterIds).output((o) => ({ listOut: o })))

];

const counterList = modelView(counterListModel, counterListView);

```

To create a dynamic list of counters we have to use the `list` function.

## Documentation

### Understanding generator functions

Turbine's use of generator functions may seem a bit puzzling at first.

For instance, it may seem like generator functions serve two different

purposes. One when they're used in the model and another when they're

used in the view

But, what they do under the hood is exactly the same in both cases.

The key to understand is that generator functions is just sugar for

calling [`chain`](#componentchain) several times in succession.

When we use `chain` on components we can combine elements and pipe

output from one component into the next. The code below combines two

`input` elements with a `span` element that shows the concatenation of

the text in the two input fields.

```typescript

input({ attrs: { placeholder: "foo" } }).chain(({ value: aValue }) =>

input().chain(({ value: bValue }) => {

const concatenated = lift((a, b) => a + b, aValue, bValue);

return span(["Concatenated text: ", concatenated]).mapTo({ concatenated });

})

);

```

However, the above code is very awkward as each invocation of `chain`

adds an extra layer of nesting. To solve this problem we use

generators.

```typescript

go(function*() {

const { value: aValue } = yield input();

const { value: bValue } = yield input();

const concatenated = lift((a, b) => a + b, aValue, bValue);

yield span(["Concatenated text: ", concatenated]);

return { concatenated };

});

```

The above code does exactly the same as the previous example. But it

is a lot easier to read!

The `go` function works like this. We yield a value with a `chain`

method. `go` then calls `chain` on the yielded value. `go` calls

`chain` with a function that continues the generator function with the

value that `chain` passes it. The end result is a value of the same

type that we yield inside the generator function. When we `yield` a

`Component` we will get an `A` back inside the generator function.

Finally we `return` a value and that value will be the output of the

component that `go` returns.

Here is another example. The following code uses `chain` explicitly.

```ts

const view = button("Accept").chain(({ click: acceptClick }) =>

button("Reject").map(({ click: rejectClick }) => ({

acceptClick,

rejectClick

}))

);

```

The above code is equivalent to the following.

```ts

const view = go(function*() {

const { click: acceptClick } = yield button("Accept");

const { click: rejectClick } = yield button("Reject");

return { acceptClick, rejectClick };

});

```

Again, the code that uses generator functions is a lot easier to read.

This is why they're useful in Turbine.

`Component` is not the only type in Turbine that has a `chain` method.

`Now` and `Behavior` does as well. And since `go` is only sugar for

calling `chain` it works with these types as well.

## API

The API documentation is incomplete. See also the

[examples](#examples), the [tutorial](#tutorial), the [Hareactive

documentation](https://github.com/funkia/hareactive) and this tutorial

about [IO](https://github.com/funkia/io).

### Component

#### `Component#map`

Mapping over a component is a way of applying a function to the output

of a component. If a component has output of type `A` then we can map

a function from `A` to `B` over the component and get a new component

whose output is of type `B`.

In the example below `input` creates a component with an object as

output. The object contains a behavior named `value`. The

function given to `map` receives the output from the component.

We then call `map` on the behavior `value` and take the length of

the string. The result is that `usernameInput` has the type

`Component>` because it's mapped output is a

number-valued behavior whose value is the current length of the text

in the input element.

```ts

const usernameInput = input({ class: "form-control" }).map((output) =>

output.value.map((s) => s.length)

);

```

#### `Component#chain`

`map` makes it possible to transform and change the output from a

component. However, it does not make it possible to take output from

one component and pipe it into another component. That is where

`chain` enters the picture. The type of the `chain` method is as

follows.

```typescript

chain((output: Output) => Component): Component;

```

The `chain` method on a components with output `Output` takes a

function that takes `Output` as argument and returns a new component.

Here is an example. An invocation `component.chain(fn)` returns a new

component that works like this:

- The output from `component` is passed to `fn`.

- `fn` returns a new component, let's call it `component2`

- The DOM-elements from `component` and `component2` are both added to

the parent.

- The output is the output from `component2`.

Here is an example.

```typescript

input().chain((inputOutput) => span(inputOutput.value));

```

The above example boils down to this:

```typescript

Create input component Create span component with text content

↓ ↓

input().chain((inputOutput) => span(inputOutput.value));

↑ ↑

Output from input-element Behavior of text in input-element

```

The result is an input element followed by a span element. When

something is written in the input the text in the span element is

updated accordingly.

### `loop`

Sometimes situations arise where there is a cyclic dependency between

two components.

For instance, you may have a function that creates a component that

shows the value of an input string-value behavior and outputs a

string-valued behavior.

```typescript

const myComponent = (b: Behavior) => span(b).chain((_) => input());

```

Now we'd have a cyclic dependency if we wanted to construct two of

these views so that the first showed the output from the second and

the second showed output from the first. With `loop` we can do it like

this:

```typescript

loop(({ output1, output2 }) =>

go(function*() {

const output1_ = yield myComponent(output2);

const output2_ = yield myComponent(output1);

return { output1: output1_, output2: output2_ };

})

);

```

The `loop` functional seems pretty magical. It has the following

signature (slightly simplified):

```ts

loop(f: (a: A) => Component): Component

```

I.e. `loop` takes a function that returns a component whose output has

the same type as the argument to the function. `loop` then passes the

output in as argument to the function. That is, `f` will as argument

receive the output from the component it returns. The only restriction

is that the output from the component must be an object with streams

and/or behaviors as values.

Visually it looks like this.

### `modelView`

The `modelView` functions makes it possible to create components where

the view is decoupled from the model and its logic.

`modelView` takes two arguments:

- The model which is a function that returns a `Now` computation. The

`Now` computation is run when the component is being created.

- The view which is a function that returns a `Component`.

`modelView` establishes a circular dependency between the model and

the view. The model returns a `Now` computation and the result of this

computation is passed into the view function. The view function then

returns a component. The output of the component is passed to the

model function.

Visually the circular dependency looks like this.

`modelView` returns a _function_ that returns a component. The

arguments given to this function will be passed along to both the

model and the view functions. This makes it easy to create components

that take input.

```js

const myComponent = modelView(

(outputFromView, arg1, arg2) => ...,

(outputFromModel, arg1, arg2) => ...

);

myComponent("foo", "bar");

```

### `list`

The `list` function is used to create _dynamic_ lists in the UI.

> **Note:** If you are familiar with frameworks like Angular or Vue then you can

> think of `list` as being similar to `ngRepeat` in Angular 1, `ngFor` in

> Angular 2, and `v-for` in Vue.

The list function has the following type.

```ts

function list(

componentCreator: (a: A) => Component,

listB: Behavior,

getKey: (a: A, index: number) => number | string = id

): Component<{}, Behavior>;

```

The first parameter, `componentCreator`, is a function that takes a value of

type `A` and returns a component. This function will be invoked to create the

elements of the dynamic list. The second argument, `listB`, is a behavior of an

array where the elements in the array are of some type `A`.

The `list` function will return a component that at any given point is time is

equivalent to applying `componentCreator` to the current array in `listB` and

then showing the resulting components one after another.

Whenever `listB` changes the component returned by `list` will react to those

changes and keep the displayed list up-to-date. To do this, the last argument,

the `getKey` function, is used to figure out how elements are moved, removed, or

added. Therefore `getKey` should return a value that is _unique_ for each element.

The following example illustrates the above. Let us say we have a list of users

where each user is an object with an `id` and a `username`:

```ts

type User = {

id: number;

username: string;

};

```

The current list of users is represented by a behavior `users: Behavior`. We want to display the users in a list with their username

being editable. This can be achieved with the list function.

```ts

list((user) => input({ value: user.username }), users, (user) => user.id);

```

If the `users` behavior starts out with the value

```js

[{ username: "foo", id: 1 }, { username: "bar", id: 2 }];

```

Then the component created by calling `list` will produce HTML like this

```html

```

Now, if the value of `users` changes into

```js

[

{ username: "baz", id: 3}

{ username: "bar", id: 2 }

{ username: "foo", id: 1 },

]

```

Then `list` will _reorder_ the two existing `input` elements and insert a new

`input` element in the beginning. Thanks to the `getKey` function `list` can

efficiently do this by applying `getKey` to the old and the current value of the

list and figure out how the elements have moved around.

### SVG

You can use embed SVG in Turbine in much the same way you'd embed it in HTML:

```js

svg({ height: "100", width: "100" }, [

circle({

cx: "50",

cy: "50",

r: "40",

fill: "red"

}),

svgText({ x: 100, y: 30 }, "Hello SVG!")

]);

```

The only element with a different name is `svgText` because `text` in Turbine is an HTML Text Node.

## Contributing

Turbine is developed by Funkia. We write functional libraries. You can

be a part of it too. Share your feedback and ideas. We also love PRs.

Run tests once with the below command. It will additionally generate

an HTML coverage report in `./coverage`.

```sh

npm test

```

Continuously run the tests with

```sh

npm run test-watch

```