https://github.com/gecko984/supervenn

supervenn: precise and easy-to-read multiple sets visualization in Python

https://github.com/gecko984/supervenn

Last synced: 8 months ago

JSON representation

supervenn: precise and easy-to-read multiple sets visualization in Python

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/gecko984/supervenn

- Owner: gecko984

- License: mit

- Created: 2020-02-11T20:32:27.000Z (almost 6 years ago)

- Default Branch: master

- Last Pushed: 2024-11-09T20:46:40.000Z (about 1 year ago)

- Last Synced: 2025-03-12T09:22:29.604Z (9 months ago)

- Language: Python

- Homepage:

- Size: 117 KB

- Stars: 337

- Watchers: 9

- Forks: 23

- Open Issues: 15

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

[](https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4016732)

# supervenn: precise and easy-to-read multiple sets visualization in Python

### What it is

**supervenn** is a matplotlib-based tool for visualization of any number of intersecting sets. It supports Python

`set`s as inputs natively, but there is a [simple workaround](#use-intersection-sizes-as-inputs-instead-of-sets) to use just intersection sizes.

Note that despite its name, `supervenn` does not produce actual (Euler-)Venn diagrams.

The easiest way to understand how supervenn diagrams work, is to compare some simple examples to their Euler-Venn

counterparts. Top row is Euler-Venn diagrams made with [matplotlib-venn](https://github.com/konstantint/matplotlib-venn)

package, bottom row is supervenn diagrams:

### Installation

`pip install supervenn`

### Requirements

Python 2.7 or 3.6+ with `numpy`, `matplotlib` and `pandas`.

### Basic usage

The main entry point is the eponymous `supervenn` function. It takes a list of python `set`s as its first and only

required argument and returns a `SupervennPlot` object.

```python

from supervenn import supervenn

sets = [{1, 2, 3, 4}, {3, 4, 5}, {1, 6, 7, 8}]

supervenn(sets, side_plots=False)

```

Each row represents a set, the order from bottom to top is the same as in the `sets` list. Overlapping parts correspond

to set intersections.

The numbers at the bottom show the sizes (cardinalities) of all intersections, which we will call **chunks**.

The sizes of sets and their intersections (chunks) are up to proportion, but the order of elements is not preserved,

e.g. the leftmost chunk of size 3 is `{6, 7, 8}`.

A combinatorial optimization algorithms is applied that rearranges the chunks (the columns of the

array plotted) to minimize the number of parts the sets are broken into. In the example above each set is in one piece

( no gaps in rows at all), but it's not always possible, even for three sets:

```python

supervenn([{1, 2}, {2, 3}, {1, 3}], side_plots=False)

```

By default, additional *side plots* are also displayed:

```python

supervenn(sets)

```

Here, the numbers on the right are the set sizes (cardinalities), and numbers on the top show how many sets does this

intersection make part of. The grey bars represent the same numbers visually.

If you need only one of the two side plots, use `side_plots='top'` or `side_plots='right'`

### Features (how to)

#### Use intersection sizes as inputs instead of sets

(New in 0.5.0). Use the utility function `make_sets_from_chunk_sizes` to produce synthetic sets of integers from your intersection sizes.

Then pass these sets to `supervenn()`:

```python

from supervenn import supervenn, make_sets_from_chunk_sizes

sets, labels = make_sets_from_chunk_sizes(sizes_df) # see below for the structure of sizes_df

supervenn(sets, labels)

```

Intersection sizes `sizes_df` should be a `pandas.DataFrame` with the following structure:

- For `N` sets, it must have `N` boolean (or 0/1) columns and the last column must be integer, so `N+1` columns in total.

- Each row represents a unique intersection (chunk) of the sets. The boolean value in column `set_x` indicate whether

this chunk lies within `set_x`. The integer value represents the size of the chunk.

For example, consider the following dataframe

```

set_1 set_2 set_3 size

0 False True True 1

1 True False False 3

2 True False True 2

3 True True False 1

```

It represents a configuration of three sets such that

- [row 0] there is one element that lies in `set_2` and `set_3` but not in `set_1`,

- [row 1] there are three elements that lie in `set_1` only and not in `set_2` or `set_3`,

- etc two more rows.

#### Add custom set annotations instead of `set_1`, `set_2` etc

Use the `set_annotations` argument to pass a list of annotations. It should be in the same order as the sets. It is

the second positional argument.

```python

sets = [{1, 2, 3, 4}, {3, 4, 5}, {1, 6, 7, 8}]

labels = ['alice', 'bob', 'third party']

supervenn(sets, labels)

```

#### Change size and dpi of the plot

Create a new figure and plot into it:

```python

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(16, 8))

supervenn(sets)

```

The `supervenn` function has `figsize` and `dpi` arguments, but they are **deprecated** and will be removed in a future

version. Please don't use them.

#### Plot into an existing axis

Use the `ax` argument:

```python

supervenn(sets, ax=my_axis)

```

#### Access the figure and axes objects of the plot

Use `.figure` and `axes` attributes of the object returned by `supervenn()`. The `axes` attribute is

organized as a dict with descriptive strings for keys: `main`, `top_side_plot`, `right_side_plot`, `unused`.

If `side_plots=False`, the dict has only one key `main`.

#### Save the plot to an image file

```python

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

supervenn(sets)

plt.savefig('myplot.png')

```

#### Use a different ordering of chunks (columns)

Use the `chunks_ordering` argument. The following options are available:

- `'minimize gaps'`: default, use an optimization algorithm to find an order of columns with fewer

gaps in each row;

- `'size'`: bigger chunks go first;

- `'occurrence'`: chunks that are in more sets go first;

- `'random'`: randomly shuffle the columns.

To reverse the order (e.g. you want smaller chunks to go first), pass `reverse_chunks_order=False` (by default

it's `True`)

#### Reorder the sets (rows) instead of keeping the order as passed into function

Use the `sets_ordering` argument. The following options are available:

- `None`: default - keep the order of sets as passed into function;

- `'minimize gaps'`: use the same algorithm as for chunks to group similar sets closer together. The difference in the

algorithm is that now gaps are minimized in columns instead of rows, and they are weighted by the column widths

(i.e. chunk sizes), as we want to minimize total gap width;

- `'size'`: bigger sets go first;

- `'chunk count'`: sets that contain most chunks go first;

- `'random'`: randomly shuffle the rows.

To reverse the order (e.g. you want smaller sets to go first), pass `reverse_sets_order=False` (by default

it's `True`)

#### Inspect the chunks' contents

`supervenn(sets, ...)` returns a `SupervennPlot` object, which has a `chunks` attribute.

It is a `dict` with `frozenset`s of set indices as keys, and chunks as values. For example,

`my_supervenn_object.chunks[frozenset([0, 2])]` is the chunk with all the items that are in `sets[0]` and

`sets[2]`, but not in any of the other sets.

There is also a `get_chunk(set_indices)` method that is slightly more convenient, because you

can pass a `list` or any other iterable of indices instead of a `frozenset`. For example:

`my_supervenn_object.get_chunk([0, 2])`.

If you have a good idea of a more convenient method of chunks lookup, let me know and I'll

implement it as well.

#### Make the plot prettier if sets and/or chunks are very different in size

Use the `widths_minmax_ratio` argument, with a value between 0.01 and 1. Consider the following example

```python

sets = [set(range(200)), set(range(201)), set(range(203)), set(range(206))]

supervenn(sets, side_plots=False)

```

Annotations in the bottom left corner are unreadable.

One solution is to trade exact chunk proportionality for readability. This is done by making small chunks visually

larger. To be exact, a linear function is applied to the chunk sizes, with slope and intercept chosen so that the

smallest chunk size is exactly `widths_minmax_ratio` times the largest chunk size. If the ratio is already greater than

this value, the sizes are left unchanged. Setting `widths_minmax_ratio=1` will result in all chunks being displayed as

same size.

```python

supervenn(sets, side_plots=False, widths_minmax_ratio=0.05)

```

The image now looks clean, but chunks of size 1 to 3 look almost the same.

#### Avoid clutter in the X axis annotations

- Use the `min_width_for_annotation` argument to hide annotations for chunks smaller than this value.

```python

supervenn(sets, side_plots=False, min_width_for_annotation=100)

```

- Pass `rotate_col_annotations=True` to print chunk sizes vertically.

- There's also `col_annotations_ys_count` argument, but it is **deprecated** and will be removed in a future version.

#### Change bars appearance in the main plot

Use arguments `bar_height` (default `1`), `bar_alpha` (default `0.6`), `bar_align` (default `edge`)', `color_cycle` (

default is current style's default palette). You can also use styles, for example:

```python

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

with plt.style.context('bmh'):

supervenn([{1,2,3}, {3,4}])

```

#### Change side plots size and color

Use `side_plot_width` (in inches, default 1) and `side_plot_color` (default `'tab:gray'`) arguments.

#### Change axes labels from `SETS`, `ITEMS` to something else

Just use `plt.xlabel` and `plt.ylabel` as usual.

#### Change other parameters

Other arguments can be found in the docstring to the function.

### Algorithm used to minimize gaps

If there are are no more than 8 chunks, the optimal permutation is found with exhaustive search (you can increase this

limit up to 12 using the `max_bruteforce_size` argument). For greater chunk counts, a randomized quasi-greedy algorithm

is applied. The description of the algorithm can be found in the docstring to `supervenn._algorithms` module.

### Less trivial examples:

#### Words with many meanings

```python

letters = {'a', 'r', 'c', 'i', 'z'}

programming_languages = {'python', 'r', 'c', 'c++', 'java', 'julia'}

animals = {'python', 'buffalo', 'turkey', 'cat', 'dog', 'robin'}

geographic_places = {'java', 'buffalo', 'turkey', 'moscow'}

names = {'robin', 'julia', 'alice', 'bob', 'conrad'}

green_things = {'python', 'grass'}

sets = [letters, programming_languages, animals, geographic_places, names, green_things]

labels = ['letters', 'programming languages', 'animals', 'geographic places',

'human names', 'green things']

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

supervenn(sets, labels , sets_ordering='minimize gaps')

```

And this is how the figure would look without the smart column reordering algorithm:

#### Banana genome compared to 5 other species

[Data courtesy of Jake R Conway, Alexander Lex, Nils Gehlenborg - creators of UpSet](https://github.com/hms-dbmi/UpSetR-paper/blob/master/bananaPlot.R)

Image from [D’Hont, A., Denoeud, F., Aury, J. et al. The banana (Musa acuminata) genome and the evolution of

monocotyledonous plants](https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11241)

Figure from original article (note that it is by no means proportional!):

Figure made with [UpSetR](https://caleydo.org/tools/upset/)

Figure made with supervenn (using the `widths_minmax_ratio` argument)

```python

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 10))

supervenn(sets_list, species_names, widths_minmax_ratio=0.1,

sets_ordering='minimize gaps', rotate_col_annotations=True, col_annotations_area_height=1.2)

```

For comparison, here's the same data visualized to scale (no `widths_minmax_ratio`, but argument

`min_width_for_annotation` is used instead to avoid column annotations overlap):

```python

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 10))

supervenn(sets_list, species_names, rotate_col_annotations=True,

col_annotations_area_height=1.2, sets_ordering='minimize gaps',

min_width_for_annotation=180)

```

It must be noted that `supervenn` produces best results when there is some inherent structure to the sets in question.

This typically means that the number of non-empty intersections is significantly lower than the maximum possible

(which is `2^n_sets - 1`). This is not the case in the present example, as 62 of the 63 intersections are non-empty,

hence the results are not that pretty.

#### Order IDs in requests to a multiple vehicle routing problem solver

This was actually my motivation in creating this package. The team I'm currently working in provides an API that solves

a variation of the Multiple Vehicles Routing Problem. The API solves tasks of the form

"Given 1000 delivery orders each with lat, lon, time window and weight, and 50 vehicles each with capacity and work

shift, distribute the orders between the vehicles and build an optimal route for each vehicle".

A given client can send tens of such requests per day and sometimes it is useful to look at their requests and

understand how they are related to each other in terms of what orders are included in each of the requests. Are they

sending the same task over and over again - a sign that they are not satisfied with routes they get and they might need

our help in using the API? Are they manually editing the routes (a process that results in more requests to our API, with

only the orders from affected routes included)? Or are they solving for several independent order sets and are happy

with each individual result?

We can use `supervenn` with some custom annotations to look at sets of order IDs in each of the client's requests.

Here's an example of an OK but not perfect client's workday:

Rows from bottom to top are requests to our API from earlier to later, represented by their sets of order IDs.

We see that they solved a big task at 10:54, were not satisfied with the result, and applied some manual edits until

11:11. Then in the evening they re-solved the whole task twice over, probably with some change in parameters.

Here's a perfect day:

They solved three unrelated tasks and were happy with each (no repeated requests, no manual edits; each order is

distributed only once).

And here's a rather extreme example of a client whose scheme of operation involves sending requests to our API every

15-30 minutes to account for live updates on newly created orders and couriers' GPS positions.

### Comparison to similar tools

#### [matplotlib-venn](https://github.com/konstantint/matplotlib-venn)

This tool plots area-weighted Venn diagrams with circles for two or three sets. But the problem with circles

is that they are pretty useless even in the case of three sets. For example, if one set is symmetrical difference of the

other two:

```python

from matplotlib_venn import venn3

set_1 = {1, 2, 3, 4}

set_2 = {3, 4, 5}

set_3 = set_1 ^ set_2

venn3([set_1, set_2, set_3], set_colors=['steelblue', 'orange', 'green'], alpha=0.8)

```

See all that zeros? This image makes little sense. The `supervenn`'s approach to this problem is to allow the sets to be

broken into separate parts, while trying to minimize the number of such breaks and guaranteeing exact proportionality of

all parts:

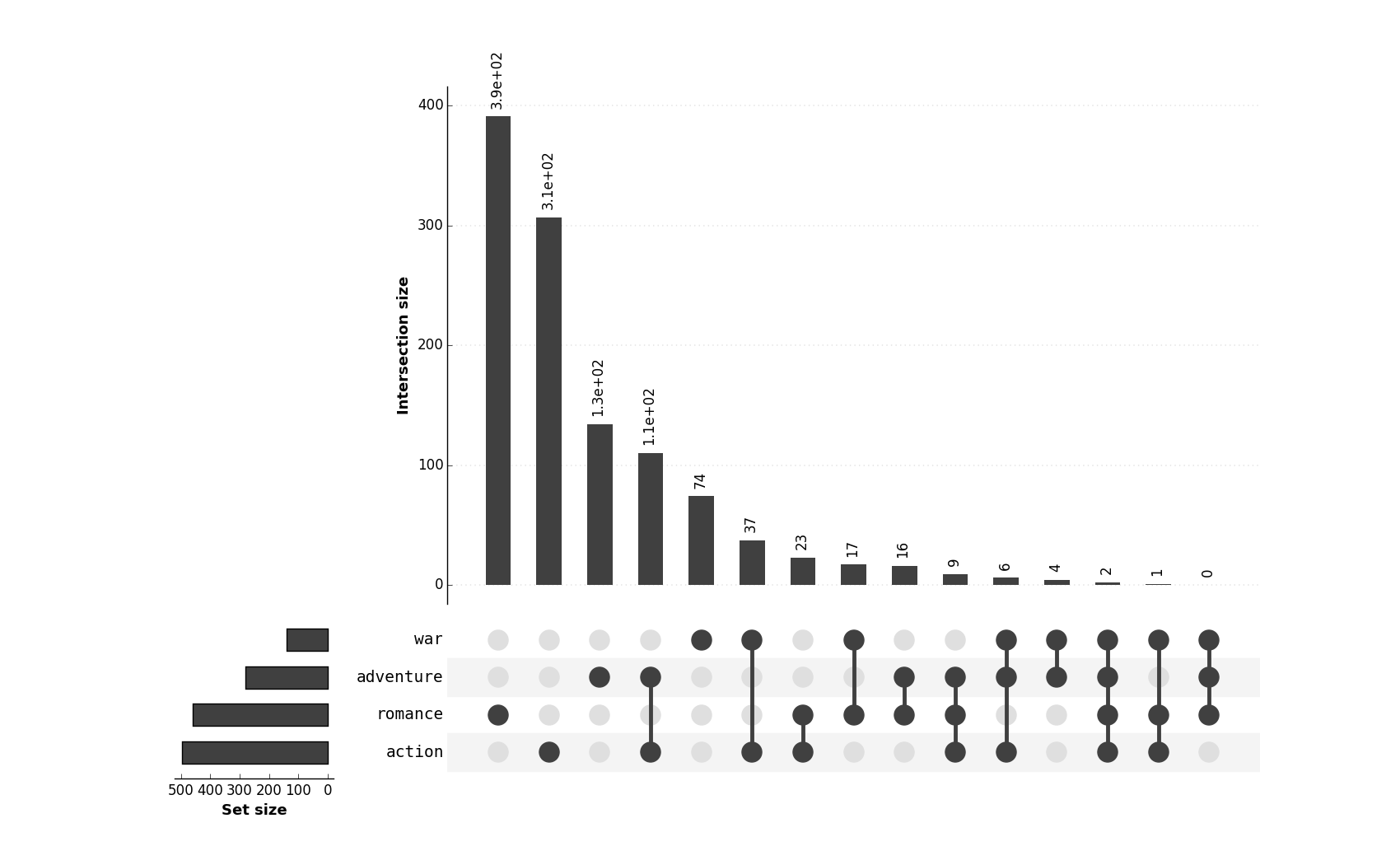

#### [UpSetR and pyUpSet](https://caleydo.org/tools/upset/)

This approach, while very powerful, is less visual, as it displays, so to say only _statistics about_ the sets, not the

sets in flesh.

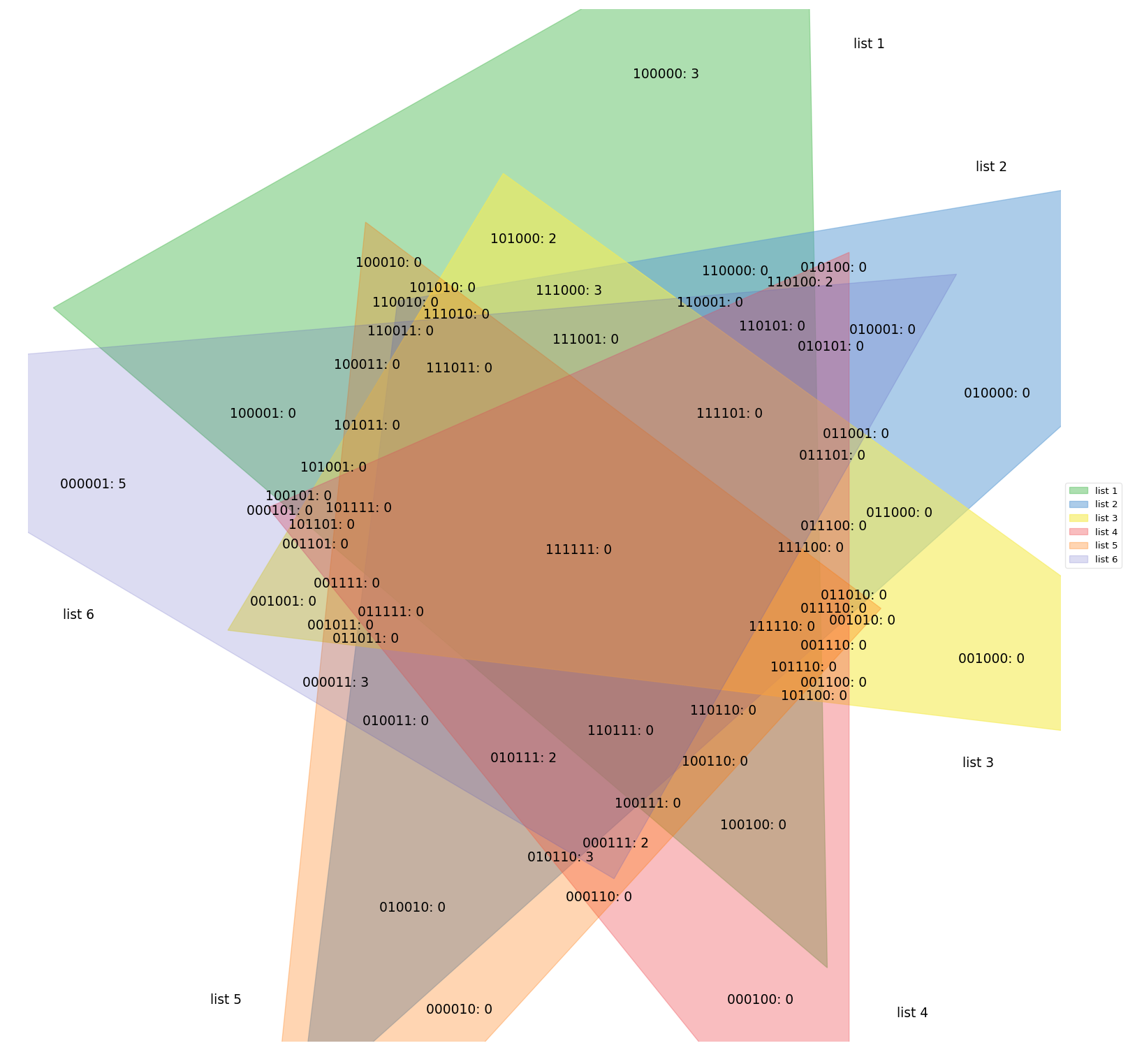

#### [pyvenn](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/wiki/tctianchi/pyvenn)

This package produces diagrams for up to 6 sets, but they are not in any way proportional. It just has pre-set images

for every given sets count, your actual sets only affect the labels that are placed on top of the fixed image,

not unlike the banana diagram above.

#### [RainBio](http://www.lesfleursdunormal.fr/static/appliweb/rainbio/index.html) ([article](https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02264217/document))

This approach is quite similar to supervenn. I'll let the reader decide which one does the job better:

##### RainBio:

##### supervenn:

_Thanks to Dr. Bilal Alsallakh for referring me to this work_

#### [Linear Diagram Generator](https://www.cs.kent.ac.uk/people/staff/pjr/linear/index.html?abstractDescription=programming_languages+1%0D%0Aletters+programming_languages+2%0D%0Aprogramming_languages+animals+green_things+1%0D%0Ageographic_places+1%0D%0Aletters+3%0D%0Ahuman_names+3%0D%0Agreen_things+1%0D%0Aprogramming_languages+geographic_places+1%0D%0Aanimals+2%0D%0Aanimals+geographic_places+2%0D%0Aanimals+human_names+1%0D%0Aprogramming_languages+human_names+1%0D%0A&width=700&height=250&guides=lines)

This tool has a similar concept, but only available as a Javascript web app with minimal functionality, and you have to

compute all the intersection sizes yourself. Apparently there is also an columns rearrangement algorithm in place, but

the target function (number of gaps within sets) is higher than in the diagram made with supervenn.

_Thanks to [u/aboutscientific](https://www.reddit.com/user/aboutscientific/) for the link._

### Credits

This package was created and is maintained by [Fedor Indukaev](https://www.linkedin.com/in/fedor-indukaev-4a52961b/).

You can contact me on Gmail and Telegram by the same username as on github.

### How can I help?

- If you like supervenn, you can click the star at the top of the page and tell other people about this tool

- If you have an idea or even an implementation of a algorithm for matrix columns rearrangement, I'll be happy to try

it, as my current algorithm is quite primitive. (The problem in question is almost the traveling salesman problem in

Hamming metric).

- If you are a Python developer, you can help by reviewing the code in any way that is convenient to you.

- If you found a bug or have a feature request, you can submit them via the

[Issues section](https://github.com/gecko984/supervenn/issues).