https://github.com/matloff/fasteR

Fast Lane to Learning R!

https://github.com/matloff/fasteR

Last synced: 7 months ago

JSON representation

Fast Lane to Learning R!

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/matloff/fasteR

- Owner: matloff

- Created: 2019-04-28T19:02:30.000Z (over 6 years ago)

- Default Branch: master

- Last Pushed: 2024-08-08T00:45:27.000Z (over 1 year ago)

- Last Synced: 2024-11-12T13:39:27.466Z (about 1 year ago)

- Language: R

- Size: 68.1 MB

- Stars: 985

- Watchers: 41

- Forks: 159

- Open Issues: 10

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

Awesome Lists containing this project

- my-awesome - matloff/fasteR - 08 star:1.1k fork:0.2k Fast Lane to Learning R! (R)

- jimsghstars - matloff/fasteR - Fast Lane to Learning R! (R)

README

# fasteR: Fast Lane to Learning R!

## *"Becoming productive in R, as fast as possible"*

### Norm Matloff, Prof. of Computer Science, UC Davis; [my bio](http://heather.cs.ucdavis.edu/matloff.html)

(See notice at the end of this document regarding copyright.)

This site is for those who know nothing of R, and maybe even nothing of

programming, and seek *QUICK, PAINLESS!* entree to the world of R.

* **FAST**: You'll already be doing good stuff in R -- useful data analysis

-- in your very first lesson.

* **For nonprogrammers:** If you're comfortable with navigating

the Web and viewing charts, you're fine. This tutorial is aimed

at you, not experienced C or Python coders.

* **Motivating:** Every lesson centers around a *real problem* to be

solved, on *real data*. The lessons do *not* consist of a few toy

examples, unrelated to the real world. The material is presented in a

conversational, story-telling manner.

* **Just the basics, no frills or polemics:**

- Notably, in the first few lessons, we do NOT use Integrated

Development Environments (IDEs). RStudio, ESS etc. are great, but

you shouldn't be burdened with learning R *and* learning an IDE at the

same time, a distraction from the goal of becoming productive in R as

fast as possible.

Note that even the excellent course by [R-Ladies

Sydney](https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1119025557830684673.html),

which does start with RStudio, laments that RStudio can be

**"way too overwhelming."**

So, in the initial lessons, we stick to the R command line, and

focus on data analysis, not tools such as IDEs, which we will cover as

an intermediate-level topic. (Some readers of this tutorial may already

be using RStudio, in which case they will just run in the RS

Console pane.)

- Coverage is mainly limited to base R. So for instance the popular

but self-described "opinionated" Tidyverse is not treated, partly

due to its controversial nature (I am a

[skeptic](http://github.com/matloff/TidyverseSkeptic)), but

again mainly because it would be an obstacle to your

becoming productive in R quickly.

While you can learn a few simple, "sanitized" things in Tidy

quickly, thinking you are learning a lot, those things are quite

limited in scope, and Tidy learners often find difficulty in

applying R to real world situations. Our tutorial here is aimed

at learners whose goal is to *use the R system productively in

their own data analysis.*

- **Pro Tip sections:** Pitfalls, handy tricks, general advice.

* **Nonpassive approach:** Passive learning, just watching the screen,

is NO learning. Coding is not a "spectator sport"; you must try the

concepts yourself, nonpassively. So there will be occasional **Your

Turn** sections, in which you the learner must devise and try your own

variants on what has been presented. Sometimes the tutorial will be

give you some suggestions, but even then, you should cook up your own

variants to try. Remember: You get out what

you put in! The more actively you work the **Your Turn**

sections, the more powerful you will be as an R coder.

**HOW MUCH NEED YOU COVER?**

* Part I is basics, Part II advanced topics

* If you intend to cover only Part I, Lessons 1 through 11 should be

considered minimal.

## Table of Contents

**PART I**

* [Lesson 1: Getting Started](#overview)

* [Lesson 2: First R Steps](#firstr)

* [Lesson 3: Vectors and Indices](#vecidxs)

* [Lesson 4: More on Vectors](#less2)

* [Lesson 5: On to Data Frames!](#less3)

* [Lesson 6: The R Factor Class](#less4)

* [Lesson 7: Extracting Rows/Columns from Data Frames](#extractdf)

* [Lesson 8: More Examples of Extracting Rows, Columns](#moreextract)

* [Lesson 9: The tapply Function](#tapply)

* [Lesson 10: Data Cleaning](#less5)

* [Lesson 11: The R List Class](#less6)

* [Lesson 12: Another Look at the Nile Data](#less7)

* [Lesson 13: Pause to Reflect](#pause1)

* [Lesson 14: Introduction to Base R Graphics ](#less8)

* [Lesson 15: More on Base Graphics ](#less9)

* [Lesson 16: Writing Your Own Functions](#less10)

* [Lesson 17: `For` Loops](#less11)

* [Lesson 18: Functions with Blocks](#ftnbl)

* [Lesson 19: Text Editing and IDes](#edt)

* [Lesson 20: If, Else, Ifelse](#ifelse)

* [Lesson 21: Do Pro Athletes Keep Fit?](#keepfit)

* [Lesson 22: Linear Regression Analysis, I](#linreg1)

* [Lesson 23: S3 Classes](#s3)

* [Lesson 24: Baseball Player Analysis (cont'd.)](#less15)

* [Lesson 25: R Packages, CRAN, Etc.](#cran)

**PART II**

* [Lesson 26: A Pause, Before Going on to Advanced Topics](#advanced)

* [Lesson 27: A First Look at ggplot2](#gg2first)

* [Lesson 28: Should You Use Functional Programming?](#appfam)

* [Lesson 29 Simple Text Processing, I](#txt)

* [Lesson 30: Simple Text Processing, II](#txt1)

* [Lesson 31: Linear Regression Analysis, II](#linreg2)

* [Lesson 32: Working with the R Date Class](#dates)

* [Lesson 33: Tips on R Coding Style and Strategy](#style)

* [Lesson 34: The Logistic Model](#logit)

* [Lesson 35: Files and Directories](#fd)

* [Lesson 36: R `while` Loops](#whl)

* [To Learn More](#forMore)

* [Thanks](#thanks)

* [Appendix: Installing and Using RStudio](#rstudio)

For the time being, the main part of this online course will be this

**README.md** file. It is set up as a potential R package, though, and

I may implement that later.

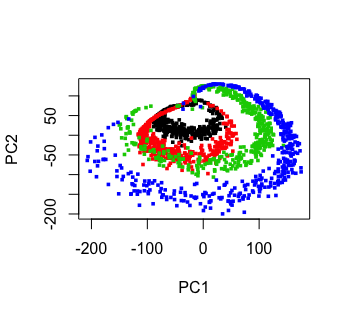

The color figure at the top of this file was generated by our

[**prVis** package](https://github.com/matloff/prVis/),

run on a famous dataset called *Swiss Roll*.

###

> 📘 Please note again, and KEEP IN MIND ALWAYS:

>

> * Nonpassive learning is absolutely key! So even if the output of an R

> command is shown here, run the command yourself in your R console, by

> copy-and-pasting from this document into the R console. Again, *you

> will get out of this tutorial what you put in.*

>

> * Similarly, the **Your Turn** sections are absolutely crucial. Devise

> your own little examples, and try them! "When in doubt, Try it

> out!" is a motto I devised for teaching. If you are unclear or

> curious about something, try it out! Just devise a little experiment,

> and type in the code. Don't worry -- you won't "break" things.

>

> * I cannot *teach* you how to

> program. I can merely give you the tools, e.g. R vectors, and some

> examples. For a given desired programming task, then, you must

> creatively put these tools together to attain the goal. Treat it like a

> puzzle! I think you'll find that if you stick with it, you'll find

> you're pretty good at it. After all, we can all work puzzles.

>

> * And for such reasons, one must remember that *there is not always a

> simple way to code a given task*. As you progress through these

> lessons, they will become increasingly complex. The essence of becoming

> a good programmer is to be patience and persistent. You then WILL

> complete those complex tasks!

### Starting out:

You'll need to [install

R](https://www.datacamp.com/community/tutorials/installing-R-windows-mac-ubuntu),

from [the R Project site](https://www.r-project.org). Start up R,

either by clicking an icon or typing `R` in a terminal window. We are

not requiring RStudio here, but if you already have it, start it; you'll

be typing into the R console, the Console pane.

As noted, this tutorial will be "bare bones." In particular, there is

no script to type your command for you. Instead, you will either

copy-and-paste from the text here into the R console, or type them there

by hand. (Note that the code lines here will all begin with the R

interactive prompt, `>`; that should not be typed.)

This is a Markdown file. You can read it right there on GitHub, which

has its own Markdown renderer. Or you can download it to your own

machine in Chrome and use the Markdown Reader extension to view it (be

sure to enable Allow Access to File URLs).

When you end your R session, exit by typing `quit()`.

Good luck! And if you have any questions, feel free to e-mail me, at

matloff@cs.ucdavis.edu

The R command prompt is `>`. Again, it will be shown here, but you don't type

it. It is just there in your R window to let you know R is inviting you

to submit a command. (If you are using RStudio, you'll see it in the

Console pane.)

So, just type `1+1` then hit Enter. Sure enough, it prints out 2 (you

were expecting maybe 12108?):

``` r

> 1 + 1

[1] 2

```

But what is that `[1]` here? It's just a row label. We'll go into that

later, not needed quite yet.

### Example: Nile River data

R includes a number of built-in datasets, mainly for illustration

purposes. One of them is **Nile**, 100 years of annual flow data on the

Nile River.

Let's find the mean flow:

``` r

> mean(Nile)

[1] 919.35

```

Here **mean** is an example of an R *function*, and in this case Nile is

an *argument* -- fancy way of saying "input" -- to that function. That

output, 919.35, is called the *return value* or simply *value*. The act

of running the function is termed *calling* the function. (Remember

these terms!)

Another point to note is that we didn't need to call R's **print**

function; the mean flow just printed out automatically. We will see the

reason for that shortly, but we could have typed,

``` r

> print(mean(Nile))

```

Function calls in R (and other languages) work "from the inside out."

Here we are asking R to find the mean of the Nile data (our inner call),

then print the result (the outer call, to the function **print**).

But whenever we are at the R `>` prompt, any expression we type will be

printed out anyway, so there is no need to call **print**.

Since there are only 100 data points here, it's not unwieldy to print

them out. Again, all we have to do is type `Nile`, no need to call

**print**:

``` r

> Nile

Time Series:

Start = 1871

End = 1970

Frequency = 1

[1] 1120 1160 963 1210 1160 1160 813 1230 1370 1140 995 935 1110 994 1020

[16] 960 1180 799 958 1140 1100 1210 1150 1250 1260 1220 1030 1100 774 840

[31] 874 694 940 833 701 916 692 1020 1050 969 831 726 456 824 702

[46] 1120 1100 832 764 821 768 845 864 862 698 845 744 796 1040 759

[61] 781 865 845 944 984 897 822 1010 771 676 649 846 812 742 801

[76] 1040 860 874 848 890 744 749 838 1050 918 986 797 923 975 815

[91] 1020 906 901 1170 912 746 919 718 714 740

```

Now you can see how the row labels work. There are 15 numbers per row

here, so the second row starts with the 16th, indicated by `[16]`. The

third row starts with the 31st output number, hence the `[31]` and so

on. So, if we want to find, say, the 78th value, we look at the third

number in the row labeled [76], obtaining 874.

Note that a set of numbers such as **Nile** is called a *vector*. This

one is a special kind of vector, a *time series*, with each element of

the vector recording a particular point in time, here consisting of the

years 1871 through 1970. We thus know that this vector has length 100

elements. But in general, we can find the length of any vector by

calling the **length** function, e.g.

``` r

> length(Nile)

[1] 100

```

If you are ever unsure of the arguments a function has, R provides the

**args** function. For instance, we will later use the **sort**

function, which orders a set of numbers from lowest to highest (or vice

versa).

For example:

``` r

> sort(Nile)

[1] 456 649 676 692 694 698 701 702 714 718 726 740 742 744 744

[16] 746 749 759 764 768 771 774 781 796 797 799 801 812 813 815

[31] 821 822 824 831 832 833 838 840 845 845 845 846 848 860 862

[46] 864 865 874 874 890 897 901 906 912 916 918 919 923 935 940

[61] 944 958 960 963 969 975 984 986 994 995 1010 1020 1020 1020 1030

[76] 1040 1040 1050 1050 1100 1100 1100 1110 1120 1120 1140 1140 1150 1160 1160

[91] 1160 1170 1180 1210 1210 1220 1230 1250 1260 1370

```

(Again, the return value from the call to **sort** was printed out

automatically.)

We can query **sort**'s arguments:

``` r

> args(sort)

function (x, decreasing = FALSE, ...)

NULL

```

We see that the **sort** function has arguments named **x**

and **decreasing** (and more, actually, but put that aside for now).

### A first graph

R has great graphics, not only in base R but also in wonderful

user-contributed packages, such as **ggplot2** and **lattice**. But

we'll stick with base-R graphics for now, and save the more powerful yet

more complex **ggplot2** for a later lesson.

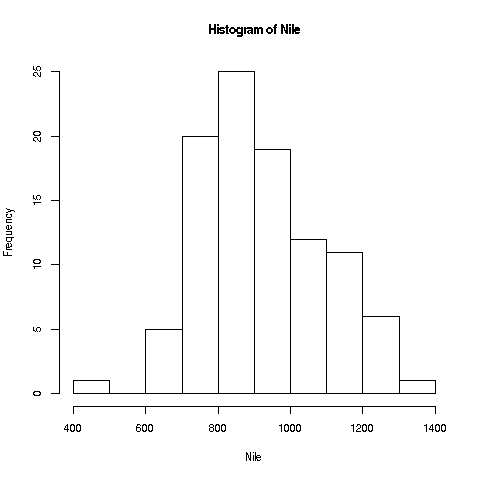

We'll start with a very simple, non-dazzling one, a no-frills histogram:

``` r

> hist(Nile)

```

Like any function, **hist** has a return value, but in this case, we

haven't save it. The return value contains the bin counts, bin

boundaries and so on.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> The *median* of a set of numbers is a value x such that half the

> numbers are less than x and half are greater than x. (There are issues

> with tied values, but not important here.) The median might be less

> than the mean or larger than it. Determine which of those two cases

> holds for the **Nile** data; the median function in R is of course

> named **median**.

>

> The **hist** function draws 10 bins for this dataset

> in the histogram by default, but you can choose other values, by

> specifying an optional second argument to the function, named

> **breaks**. E.g.

> ``` r

> > hist(Nile,breaks=20)

> ```

>

> would draw the histogram with 20 bins. Try plotting using several

> different large and small values of the number of bins.

**Note:** The **hist** function, as with many R functions, has many

different options, specifiable via various arguments. For now, we'll

just keep things simple, and resist the temptation to explore them all,

but R has lots of online help, which you can access via `?`. E.g.

typing

``` r

> ?hist

```

will tell you to full story on all the options available for the

**hist** function. Again, there are far too many for you to digest for

now (most users don't ever find a need for the more esoteric ones), but

it's a vital resource to know.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Many people like to designate functions by adding parentheses. For

> instance, instead of writing something like, "The **length** function

> often comes in handy," they will write, "The **length()** function

> often comes in handy," in order to make sure others know they are

> talking about a function. I do that myself sometimes, but it can lead

> to trouble in some settings. Consider:

>

> ``` r

> > args(sort)

> function (x, decreasing = FALSE, ...)

> NULL

> > args(sort())

> Error in sort.default() : argument "x" is missing, with no default

> ```

>

> What went wrong? In the first case, we asked **args** about an object

> **sort** that happens to be of type 'function'. In the second case, we

> actually *called* **sort**. And the latter function itself expected an

> argument, which we did not supply. (And one wouldn't have been

> appropriate anyway.)

>

> The problem here was rather obvious--well, many things are "obvious"

> in retrospect, right?--, but it can occur much more

> subtly as well.

>

> This illustrates the point that in coding, one must be extremely careful

> in recognizing subtle differences, in this case between a *function* and

> a *call* to that function. In ordinary English, we might say, "That car

> wants to turn left" instead of "The *driver* of that car wants to turn

> left," but in coding we must be very picky.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Write code to sort the **Nile** data from largest value to smallest,

> rather than vice versa.

>

> By default, calling **hist()** will display that graph, but we can

> suppress display, by setting one of its arguments. If we wish to save

> the return value of this function, we may wish to suppress the

> display. Check the online help to determine which argument does this,

> and verify that it works, i.e. it does suppress display.

>

> Look up the **order** function ('?order'), and try it out on the

> **Nile** data, and do a check that it is working as you expect.

>

## Lesson 3: Vectors and Indices

Say we want to find the mean river flow after year 1950.

The above output said that the **Nile** series starts in 1871. That

means 1951 will be the 81st year, and the 100th will be 1970. How do we

designate the 81st through 100th elements in this data?

Individual elements can be accessed using *subscripts* or *indices*

(singular is *index*), which are specified using brackets, e.g.

``` r

> Nile[2]

[1] 1160

```

for the second element (the output we saw earlier shows that the second

element is indeed 1160). The value 2 here is the index.

The **c** ("concatenate") function builds a vector, stringing several

numbers together. E.g. we can get the 2nd, 5th and 6th elements of

**Nile**:

``` r

> Nile[c(2,5,6)]

[1] 1160 1160 1160

```

If we wish to build a vector of *consecutive* numbers, we can use the

"colon" notation:

``` r

> Nile[c(2,3,4)]

[1] 1160 963 1210

> Nile[2:4]

[1] 1160 963 1210

```

As you can see, 2:4 is shorter way to specify the vector c(2,3,4).

So, 81:100 means all the numbers from 81 to 100. Thus

**Nile[81:100]** specifies the 81st through 100th elements in the **Nile**

vector.

Then to answer the above question on the mean flow during 1951-1971, we

can do

``` r

> mean(Nile[81:100])

[1] 877.05

```

> **NOTE:** Observe how the above reasoning process worked. We had a

> goal, to find the mean river flow after 1950. We knew we had some tools

> available to us, namely the **mean** function and R vector indices. We

> then had to figure out a way to combine these tools in a manner that

> achieves our goal, which we did.

>

> This is how use of R works in general. As you go through this tutorial,

> you'll add more and more to your R "toolbox." Then for any given goal,

> you'll rummage around in that toolbox, and eventually figure out the

> right set of tools for the goal at hand. Sometimes this will require

> some patience, but you'll find that the more you do, the more adept you

> become.

If we plan to do more with that time period, we should make a copy of

it:

``` r

> n81100 <- Nile[81:100]

> mean(n81100)

[1] 877.05

> sd(n81100)

[1] 125.5583

```

The function **sd** finds the standard deviation.

Note that we used R's *assignment operator* here to copy ("assign")

those particular **Nile** elements to **n81100**. (In most situations,

you can use `=` instead of `<-`, but why worry about what the exceptions

might be? They are arcane, so it's easier just to always use `<-`.

And though "keyboard shortcuts" for this are possible, again let's just

stick to the basics for now.)

Note too that though we will speak of the above operation as having

"extracted" the 81st through 100th elements of **Nile**, we have merely

made a copy of those elements. The original vector **Nile** remains

intact.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> We can pretty much choose any name we want; "n81100" just was chosen

> to easily remember this new vector's provenance. (But names can't

> include spaces, and must start with a letter.)

Note that **n81100** now is a 20-element vector. Its first element is

now element 81 of **Nile**:

``` r

> n81100[1]

[1] 744

> Nile[81]

[1] 744

```

Keep in mind that although **Nile** and **n81100** now have identical

contents, they are *separate* vectors; if one changes, the other will

not.

Recall that another oft-used function is **length**, which gives the

number of elements in the vector, e.g.

``` r

> length(Nile)

[1] 100

```

Can you guess the value of **length(n81100)**? Type this expression in

at the '>' prompt to check your answer.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Write code to find the mean height of the Nile the

> over the years 1945-1960.

>

> In which period did the Nile have a larger mean height, the first 50

> years or the last 50?

### Recap: What have we learned in these first two lessons?

* Starting and exiting R.

* Some R functions: **mean**, **hist**, **length**.

* R vectors, and vector indices.

* Extracting vector subsets.

* Forming vectors, using the function **c** and ":".

Not a bad start! And needless to say, you'll be using all of these

frequently in the subsequent lessons and in your own usage of R.

Continuing along the Nile, say we would like to know in how many years

the level exceeded 1200. Let's first introduce R's **sum** function:

``` r

> sum(c(5,12,13))

[1] 30

```

Here the ***c*** function built a vector consisting of

5, 12 and 13. That vector was then fed into the **sum** function,

returning 5+12+13 = 30.

By the way, the above is our first example of *function composition*,

where the output of one function, ***c*** here, is fed as input into

another, **sum** in this case.

We can now use this to answer our question on the **Nile** data:

``` r

> sum(Nile > 1200)

[1] 7

```

The river level exceeded 1200 in 7 years.

**But how in the world did that work?** Bear with me a bit here. Let's

look at a small example first:

``` r

> x <- c(5,12,13)

> x

[1] 5 12 13

> x > 8

[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE

> sum(x > 8)

[1] 2

```

First, notice something odd here, in the expression **x > 8**. Here

**x** is a vector, 3 elements in length, but 8 is just a number. It

would seem that it's nnonsense to ask whether a vector is greater than a

number; they're different animals.

But R makes them "the same kind" of animal, by extending that number 8

to a 3-element vector 8,8,8. This is called *recycling*. This sets up

an element-by-element comparison: Then, the 5 in **x** is compared to

the first 8, yielding FALSE i.e. 5 is NOT greater than 8. Then 12 is

compared to the second 8, yielding TRUE, and then the comparison of 13

to the third 8 yields another TRUE. So, we get the vector

FALSE,TRUE,TRUE.

Fine, but how will **sum** add up some TRUEs and FALSEs? The

answer is that R, like most computer languages, treats TRUE and FALSE as

1 and 0, respectively. So we summed the vector (0,1,1), yielding 2.

Getting back to the question of the number of years in which the Nile

flow exceeded 1200, let's look at that expression again:

``` r

> sum(Nile > 1200)

```

Since the vector **Nile** has length 100, that number 1200 will be

recycled into a vector of one hundred copies of 1200. The '>'

comparison will then yield 100 TRUEs and FALSEs, so summing gives us the

number of TRUEs, exactly what we want.

A question related to *how many* years had a flow above 1200 is *which*

years had that property. Well, R actually has a **which** function:

``` r

> which(Nile > 1200)

[1] 4 8 9 22 24 25 26

```

So the 4th, 8th, 9th etc. elements in **Nile** had the queried property.

(Note that those were years 1874, 1878 and so on.)

In fact, that gives us another way to get the count of the years with

that trait:

``` r

> which1200 <- which(Nile > 1200)

> which1200

[1] 4 8 9 22 24 25 26

> length(which1200)

[1] 7

```

Of course, as usual, my choice of the variable name "which1200" was

arbirary, just something to help me remember what is stored in that

variable.

R's **length** function does what it says, i.e. finding the length of a

vector. In our context, that gives us the count of years with flow

above 1200.

And, what were the river flows in those 7 years?

``` r

> which1200 <- which(Nile > 1200)

> Nile[which1200]

[1] 1210 1230 1370 1210 1250 1260 1220

```

Finally, something a little fancier. We can combine steps above:

``` r

> Nile[Nile > 1200]

[1] 1210 1230 1370 1210 1250 1260 1220

```

We just "eliminated the middle man," **which1200**. The R interpreter

saw our "Nile > 1200", and thus generated the corresponding TRUEs and

FALSEs. The R interpreter then treated those TRUEs and

FALSEs as subscripts in **Nile**, thus extracting the desired data.

Now, we might add here, "Don't try this at home, kids." For

beginners, it's really easier and more comfortable to break things into

steps. Once, you become experienced at R, you may wish to start

skipping steps.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Say we are interested in years in which the Nile had under 950. Write

> code to determine (a) how many such years there were, (b) which

> specific years these were, and (c) the median height during those

> years.

>

> Try a few other experiments of your choice using **sum**.

> I'd suggest starting with finding the sum of the first 25 elements in

> **Nile**. You may wish to start with experiments on a small vector, say

> (2,1,1,6,8,5), so you will know that your answers are correct.

> Remember, you'll learn best nonpassively. Code away!

>

> Also very useful is the notion of negative indices, e.g.

>

> ``` r

> > x <- c(5,12,13,8)

> > x[-1]

> [1] 12 13 8

> ```

>

> Here we are asking for all of **x** *except* for **x[1]**. Can you

> guess what **x[c(-1,-4)]** evaluates to? Guess first, then try it out.

Concerning that last point:

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> A catchy motto I teach students is, "When in doubt, Try it out!" Get

> in the habit of devising little experiments that you can try to check

> the behavior of some R aspect that you are unsure of.

### Recap: What have we learned in this lesson?

Here you've refined your skillset for R vectors, learning R's recycling

feature, and two tricks that R users employ for finding counts of things.

Once again, as you progress through this tutorial, you'll see that these

things are used a lot in R.

## Lesson 5: On to Data Frames!

Right after vectors, the next major workhorse of R is the *data frame*.

It's a rectangular table consisting of one row for each data point.

Say we have height, weight and age on each of 100 people. Our data

frame would have 100 rows and 3 columns. The entry in, e.g., the second

row and third column would be the age of the second person in our data.

The second row as a whole would be all the data for that second person,

i.e. the height, weight and age of that person.

**Note that that row would also be considered a vector. The third column

as a whole would be the vector of all ages in our dataset.**

As our first example, consider the **ToothGrowth** dataset built-in to

R. Again, you can read about it in the online help by typing

``` r

> ?ToothGrowth

```

The data turn out to be on guinea pigs, with orange juice or

Vitamin C as growth supplements. Let's take a quick look

from the command line.

``` r

> head(ToothGrowth)

len supp dose

1 4.2 VC 0.5

2 11.5 VC 0.5

3 7.3 VC 0.5

4 5.8 VC 0.5

5 6.4 VC 0.5

6 10.0 VC 0.5

```

R's **head** function displays (by default) the first 6 rows of the

given dataframe. We see there are length, supplement and dosage

columns, which the curator of the data decided to name 'len', 'supp' and

'dose'. Each of column is an R vector, or in the case of the second

column, a vector-like object called a *factor*, to be discussed

shortly).

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> To avoid writing out the long words repeatedly, it's handy to

> make a copy with a shorter name.

``` r

> tg <- ToothGrowth

```

Dollar signs are used to denote the individual columns, e.g.

**ToothGrowth$dose** for the dose column. So for instance, we can print

out the mean tooth length:

``` r

> mean(tg$len)

[1] 18.81333

```

Subscripts/indices in data frames are pairs, specifying row and column

numbers. To get the element in row 3, column 1:

``` r

> tg[3,1]

[1] 7.3

```

which matches what we saw above in our **head** example. Or, use the

fact that **tg$len** is a vector:

``` r

> tg$len[3]

[1] 7.3

```

The element in row 3, column 1 in the *data frame* **tg** is element 3

in the *vector* **tg$len**. This duality between data frames and

vectors is often exploited in R.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> The above examples are fundamental to R, so you should

> conduct a few small experiments on your own this time, little variants

> of the above. The more you do, the better!

For any subset of a data frame **d**, we can extract whatever rows and

columns we want using the format

``` r

d[the rows we want, the columns we want]

```

Some data frames don't have column names, but that is no obstacle. We

can use column numbers, e.g.

``` r

> mean(tg[,1])

[1] 18.81333

```

Note the expression '[,1]'. Since there is a 1 in the second position,

we are talking about column 1. And since the first position, before the

comma, is empty, no rows are specified -- so *all* rows are included.

That boils down to: all of column 1.

A key feature of R is that one can extract subsets of data frames,

just as we extracted subsets of vectors earlier. For instance,

``` r

> z <- tg[2:5,c(1,3)]

> z

len dose

2 11.5 0.5

3 7.3 0.5

4 5.8 0.5

5 6.4 0.5

```

Here we extracted rows 2 through 5, and columns 1 and 3, assigning the

result to **z**. To extract those columns but keep all rows, do

``` r

> y <- tg[ ,c(1,3)]

```

i.e. leave the row specification field empty.

By the way, note that the three columns are all of the same length, a

requirement for data frames. And what is that common length in this

case? R's **nrow** function tells us the number of rows in any data

frame:

``` r

> nrow(ToothGrowth)

[1] 60

```

Ah, 60 rows (60 guinea pigs, 3 measurements each).

Or, alternatively:

``` r

> tg <- ToothGrowth

> length(tg$len)

[1] 60

> length(tg$supp)

[1] 60

> length(tg$dose)

[1] 60

```

So now you know four ways to do the same thing. But isn't one enough?

Of course. But in this get-acquainted period, reading all four will

help reinforce the knowledge you are now accumulating about R. So,

*make sure you understand how each of those four approaches produced the

number 60.*

The **head** function works on vectors too:

``` r

> head(ToothGrowth$len)

[1] 4.2 11.5 7.3 5.8 6.4 10.0

```

Like many R functions, **head** has an optional second argument,

specifying how many elements to print:

``` r

> head(ToothGrowth$len,10)

[1] 4.2 11.5 7.3 5.8 6.4 10.0 11.2 11.2 5.2 7.0

```

You can create your own data frames -- good for devising little tests of

your understanding -- as follows:

``` r

> x <- c(5,12,13)

> y <- c('abc','de','z')

> d <- data.frame(x,y)

> d

x y

1 5 abc

2 12 de

3 13 z

```

Look at that second line! Instead of vectors consisting of numbers,

one can form vectors of character strings, complete with indexing

capability, e.g.

``` r

> y <- c('abc','de','z')

> y[2]

[1] "de"

```

As noted, all the columns in a data frame must be of the same length.

Here **x** consists of 3 numbers, and **y** consists of 3 character

strings. (The string is the unit in the latter. The number of

characters in each string is irrelevant.)

One can use negative indices for rows and columns as well, e.g.

``` r

> z <- tg[,-2]

> head(z)

len dose

1 4.2 0.5

2 11.5 0.5

3 7.3 0.5

4 5.8 0.5

5 6.4 0.5

6 10.0 0.5

```

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Devise your own little examples with the **ToothGrowth** data. For

> instance, write code that finds the number of cases in which the tooth

> length was less than 16, and which rows had the VC supplement..

>

> Also, try some examples with another built-in R dataset, **faithful**.

> This one involves the Old Faithful geyser in Yellowstone National Park

> in the US. The first column gives duration of the eruption, and the

> second has the waiting time since the last eruption.

>

> For instance, write code to find the maximum value of the durations,

> and also write code to determine the index (1st, 2nd, 3rd, ...) of

> that largest duration value.

>

> As mentioned, these operations are key features of R, so devise and

> run as many examples as possible; err on the side of doing too many!

### Recap: What have we learned in this lesson?

As mentioned, the data frame is the fundamental workhorse of R. It is

made up of columns of vectors (of equal lengths), a fact that often

comes in handy.

Unlike the single-number indices of vectors, each element in a data

frame has 2 indices, a row number and a column number. One can specify

sets of rows and columns to extra subframes.

One can use the R **nrow** function to query the number of rows in a

data frame; **ncol** does the same for the number of columns.

Each object in R has a *class*. The number 3 is of the **'numeric'**

class, the character string 'abc' is of the **'character'** class, and

so on. (In R, class names are quoted; one can use single or double

quotation marks.) Note that vectors of numbers are of **'numeric'**

class too; actually, a single number is considered to be a vector of

length 1. So, **c('abc','xw')**, for instance, is **'character'**

as well.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Computers require one to be very, very careful and very, very precise.

> In that expression **c('abc','xw')** above, one might wonder why it does

> not evaluate to 'abcxw'. After all, didn't I say that the 'c' stands

> for "concatenate"? Yes, but the **c** function concatenates *vectors*.

> Here 'abc' is a vector of length 1 -- we have *one* character string,

> and the fact that it consists of 3 characters is irrelevant -- and

> likewise 'xw' is one character string. So, we are concatenating a

> 1-element vector with another 1-element vector, resulting in a 2-element

> vector.

What about **tg** and **tg$supp** in the Vitamin C example above? What

are their classes?

``` r

> class(tg)

[1] "data.frame"

> class(tg$supp)

[1] "factor"

```

R factors are used when we have *categorical* variables. If in a

genetics study, say, we have a variable for hair color, that might

comprise four categories: black, brown, red, blond. We can find the

list of categories for **tg$supp** as follows:

``` r

> levels(tg$supp)

[1] "OJ" "VC"

```

The categorical variable here is **supp**, the name the creator of this

dataset chose for the supplement column. We see that there are two categories

(*levels*), either orange juice or Vitamin C.

Note carefully that the values of an R factor must be quoted. Either

single or double quote marks is fine (though the marks don't show

up when we use **head**).

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> The R **factor** class is one of the most powerful aspects of R. We

> will acquire this skill gradually in the coming lessons. Make sure to

> really become skilled in it.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> As mentioned, R includes many built-in datasets, a list of which you

> may obtain via the call **data()**. One of them is **CO2**. Using

> the **class()** function as above, determine which of the columns in

> this dataset, if any, are of **factor** class.

## Lesson 7: Extracting Rows/Columns from Data Frames

(The reader should cover this lesson especially slowly and carefully.

The concepts are simple, but putting them together requires careful

inspection.)

First, let's review what we saw in a previous lesson:

``` r

> which1200 <- which(Nile > 1200)

> Nile[which1200]

[1] 1210 1230 1370 1210 1250 1260 1220

```

There, we saw how to extract *vector elements*. We can do something

similar to extract *data frame rows or columns*. Here is how:

Continuing the Vitamin C example, let's compare mean tooth length for

the two types of supplements. Here is the code:

``` r

> whichOJ <- which(tg$supp == 'OJ')

> whichVC <- which(tg$supp == 'VC')

> mean(tg[whichOJ,1])

[1] 20.66333

> mean(tg[whichVC,1])

[1] 16.96333

```

In the first two lines above, we found which rows in **tg** (or

equivalently, which elements in **tg$supp**) had the OJ supplement, and

recorded those row numbers in **whichOJ**. Then we did the same for VC.

Now, look at the expression **tg[whichOJ,1]**. Remember, data frames

are accessed with two subscript expressions, one for rows, one for

colums, in the format

``` r

d[the rows we want, the columns we want]

```

So, **tg[whichOJ,1]** says to restrict attention to the OJ rows, and

only column 1, tooth length. We then find the mean of those restricted

numberss. This turned out to be 20.66333. Then do the same for VC.

Again, if we are pretty experienced, we can skip steps:

``` r

> tgoj <- tg[tg$supp == 'OJ',]

> tgvc <- tg[tg$supp == 'VC',]

> mean(tgoj$len)

[1] 20.66333

> mean(tgvc$len)

[1] 16.96333

```

Either way, we have the answer to our original question: Orange juice appeared

to produce more growth than Vitamin C. (Of course, one might form a

confidence interval for the difference etc.)

### Recap: What have we learned in this lesson?

Just as we learned earlier how to use a sequence of TRUE and FALSE

values to extract a parts of a vector, we now see how to do the

analogous thing for data frames: **We can use a sequence of TRUE and FALSE

values to extract a certain rows or columns from a data frame.**

It is imperative that the reader fully understand this lesson before

continuing, trying some variations of the above example on his/her own.

We'll be using this technique often in this tutorial, and it is central

to R usage in the real world.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Try some of these operations on R's built-in **faithful** dataset.

> For instance, extract the sub-data frame consisting of all rows in

> which the waiting time was more than 80 minutes.

## Lesson 8: More Examples of Extracting Rows, Columns

Often we need to extract rows or columns from a data frame, subject to

more than one condition. For instance, say we wish to extract from

**tg** the sub-data frame consisting of rows in which

OJ was the treatment and length was less than 8.8.

We could do this, using the ampersand symbol '&', which means a logical

AND operation:

``` r

> tg[tg$supp=='OJ' & tg$len < 8.8,]

len supp dose

37 8.2 OJ 0.5

```

Ah, it turns out that only one case satisfied both conditions.

If we want all rows that satisfy at least one of the conditions, not

necessarily both, then we use the OR operator, '|'. Say we want to

obtain all rows in which either **len** is greater than 28 or the

treatment dose was 1.0 or both:

``` r

> tg[tg$len > 28 | tg$dose == 1.0,]

len supp dose

11 16.5 VC 1

12 16.5 VC 1

13 15.2 VC 1

14 17.3 VC 1

15 22.5 VC 1

16 17.3 VC 1

17 13.6 VC 1

18 14.5 VC 1

19 18.8 VC 1

20 15.5 VC 1

23 33.9 VC 2

26 32.5 VC 2

30 29.5 VC 2

41 19.7 OJ 1

42 23.3 OJ 1

43 23.6 OJ 1

44 26.4 OJ 1

45 20.0 OJ 1

46 25.2 OJ 1

47 25.8 OJ 1

48 21.2 OJ 1

49 14.5 OJ 1

50 27.3 OJ 1

56 30.9 OJ 2

59 29.4 OJ 2

```

By the way, note that the original row numbers are displayed too. For

example, the first case satisfying the conditions was row number 11 in

the original data frame **tg**.

Typically we want not only to extract part of the data frame, but also

save the results:

``` r

> w <- tg[tg$len > 28 | tg$dose == 1.0,]

```

Again, I chose the name 'w' arbitrarily. Names must begin with a

letter, and consist only of letters, digits and a few special

characters such as '-' or '.'

Note that **w** is a new data frame, on which we can perform the usual

operations, e.g.

``` r

> head(w)

len supp dose

11 16.5 VC 1

12 16.5 VC 1

13 15.2 VC 1

14 17.3 VC 1

15 22.5 VC 1

16 17.3 VC 1

> nrow(w)

[1] 25

```

We may only be interested in say, *how many* cases satisfied the given

conditions. As before, we can use **nrow** for that, as seen here.

As seen early, we can also extract columns. Say our analysis will use

only tooth length and dose. We write 'c(1,3)' in the "what columns we

want" place, indicating columns 1 and 3:

``` r

> lendose <- tg[,c(1,3)]

> head(lendose)

len dose

1 4.2 0.5

2 11.5 0.5

3 7.3 0.5

4 5.8 0.5

5 6.4 0.5

6 10.0 0.5

```

From now on, we would work with **lendose** instead of **tg**.

It's a little nicer, though, the specify the columns by name instead of

number:

``` r

> lendose <- tg[,c('len','dose')]

> head(lendose)

len dose

1 4.2 0.5

2 11.5 0.5

3 7.3 0.5

4 5.8 0.5

5 6.4 0.5

6 10.0 0.5

```

The logical operations work on vectors too. For example, say in the

**Nile** data we wish to know how many years had flows in the extremes,

say below 800 or above 1300:

``` r

> exts <- Nile[Nile < 800 | Nile > 1300]

> head(exts)

[1] 1370 799 774 694 701 692

> length(exts)

[1] 27

```

By the way, if this count were our only interest, i.e. we have no

further use for **exts**, we can skip assigning to **exts**, and do

things directly:

``` r

> length(Nile[Nile < 800 | Nile > 1300])

[1] 27

```

This is fine for advanced, experienced R users, but really, "one step at

a time" is better for beginners. It's clearer, and most important,

easier to debug if something goes wrong.

In the **Nile** data, say we are interested in the change in river

height from one year to the next. Recall the first few elements:

``` r

> head(Nile)

[1] 1120 1160 963 1210 1160 1160

```

So the was a change of +40, then a change of -197 and so on. How can we

code up a vector of all the changes?

``` r

> nile1 <- Nile[-1]

> head(nile1)

[1] 1160 963 1210 1160 1160 813

> z <- nile1 - Nile

Warning message:

In `-.default`(nile1, Nile) :

longer object length is not a multiple of shorter object length

> head(z)

[1] 40 -197 247 -50 0 -347

```

Let's ignore the warning for a moment. What happened here?

1. Deleting element 1 of **Nile** had the effect of shifting all the

elments leftward by one spot; i.e. **nile[1]** is **Nile[2][**,

**nile[2]** is **Nile[3]** and so on.

2. The subtraction **nile1 - Nile** is done element-by-element, so

it produced **nile1[1] - Nile[1]**, **nile1[2] - Nile[2]** etc.

But those are the year-to-year differences in the original **Nile**

data, so **z** now has exactly what we want!

3. But, that subtraction wasn't quite right. As the warning tells us,

we subtracted a vector of length 100 from one of length 99. R used

recycling to extend the latter to length 100, but the 100th element

of **z** is meaningless. We should probably finish by running

``` r

z <- z[-100]

```

In extracting various vector elements, rows or columns, we

don't have to use the same ordering, e.g.

``` r

> x <- c(5,12,13,8,168)

>

> x

[1] 5 12 13 8 168

> w <- x[c(5,4)]

> w

[1] 168 8

> x[c(4,5)] <- w

> x

[1] 5 12 13 168 8

```

We extracted the 5th and 4th elements of **x**, in that order. We

then assigned the result to **w**, and (whether we had some purpose in

mind or just for fun), we assigned the reversed numbers back into **x**.

Nor do the extracted entities need to be contiguous, e.g.

``` r

> x[c(1,4)]

[1] 5 168

```

### Recap: What we've learned in this lesson

Here we got more practice in manipulating data frames, and were

introduced to the logical operators '&' and '|'. We also saw another

example of using **nrow** as a means of counting how many rows satisfy

given conditions.

Again, these are all "bread and butter" operations that arise quite

freqently in real world R usage.

By the way, note how the essence of R is "combining little things in

order to do big things," e.g. combining the subsetting operation, the

'&' operator, and **nrow** to get a count of rows satisfying given

conditions. This too is the "bread and butter" of R. It's up to you,

the R user, to creatively combine R's little operations (and later, some

big ones) to achieve whatever goals you have for your data. *Programming

is a creative process*. It's like a grocery store and cooking: The

store has lots of different potential ingredients, and you decide which

ones to buy and combine into a meal.

> ❄️ Your Turn

> Try some of these operations on R's built-in **faithful** dataset.

>

> 1. Find the number of rows for which the **eruptions**

> column was greater than 3 and waiting time was more than 80 minutes.

>

> 2. Add code to print out the row numbers of those cases.

>

## Lesson 9: The tapply Function

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Often in R there is a shorter, more

> compact way of doing things. That's the case here; we can use the

> magical **tapply** function in the above example. In fact, we can do it

> in just one line.

The general form of a call to **tapply** is

``` r

tapply(what to split, what criterion to use for splitting,

what to do with the resulting grouped data)

```

``` r

> tapply(tg$len,tg$supp,mean)

OJ VC

20.66333 16.96333

```

In English: "Split the vector **tg$len** into two groups, according to

the value of **tg$supp**, then apply **mean** to each group." Note that

the result was returned as a vector, which we could save by assigning it

to, say **z**:

``` r

> z <- tapply(tg$len,tg$supp,mean)

> z[1]

OJ

20.66333

> z[2]

VC

16.96333

```

By the way, **z** is not only a vector, but also a *named* vector,

meaning that its elements have names, in this case 'OJ' and 'VC'.

Saving can be quite handy, because we can use that result in subsequent

code.

To make sure it is clear how this works, let's look at a small

artificial example:

``` r

> x <- c(8,5,12,13)

> g <- c('M',"F",'M','M')

```

Suppose **x** is the ages of some kids, who are a boy, a girl, then two more

boys, as indicated in **g**. For instance, the 5-year-old is a girl.

Let's call **tapply**:

``` r

> tapply(x,g,mean)

F M

5 11

```

That call said, "Split **x** into two piles, according to the

corresponding elements of **g**, and then find the mean in each pile.

Note that it is no accident that **x** and **g** had the same number of

elements above, 4 each. If on the contrary, **g** had 5 elements, that

fifth element would be useless -- the gender of a nonexistent fifth

child's age in **x**. Similarly, it wouldn't be right if **g** had had

only 3 elements, apparently leaving the fourth child without a specified

gender.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> If **g** had been of the wrong length, we would have gotten an error,

> "Arguments must be of the same length." This is a common error in R

> code, so watch out for it, keeping in mind WHY the lengths must be the

> same.

Instead of **mean**, we can use any function as that third argument in

**tapply**. Here is another example, using the built-in dataset

**PlantGrowth**:

``` r

> tapply(PlantGrowth$weight,PlantGrowth$group,length)

ctrl trt1 trt2

10 10 10

```

Here **tapply** split the **weight** vector into subsets according to

the **group** variable, then called the **length** function on each

subset. We see that each subset had length 10, i.e. the experiment had

assigned 10 plants to the control, 10 to treatment 1 and 10 to treatment

2.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> One of the most famous built-in R datasets is

> **mtcars**, which has various measurements on cars from the 60s and 70s.

> Lots of opportunties for you to cook up little experiments here!

>

> You may wish to start by comparing the mean miles-per-gallon values

> for 4-, 6- and 8-cylinder cars. Another suggestion would be to find

> how many cars there are in each cylinder category, using **table**.

> As usual, the more examples you cook up here, the better!

By the way, the **mtcars** data frame has a "phantom" column.

``` r

> head(mtcars)

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1

```

That first column seems to give the make (brand) and model of the car.

Yes, it does -- but it's not a column. Behold:

``` r

> head(mtcars[,1])

[1] 21.0 21.0 22.8 21.4 18.7 18.1

```

Sure enough, column 1 is the mpg data, not the car names. But we see

the names there on the far left! The resolution of this seeming

contradiction is that those car names are the *row names* of this data

frame:

``` r

> row.names(mtcars)

[1] "Mazda RX4" "Mazda RX4 Wag" "Datsun 710"

[4] "Hornet 4 Drive" "Hornet Sportabout" "Valiant"

[7] "Duster 360" "Merc 240D" "Merc 230"

[10] "Merc 280" "Merc 280C" "Merc 450SE"

[13] "Merc 450SL" "Merc 450SLC" "Cadillac Fleetwood"

[16] "Lincoln Continental" "Chrysler Imperial" "Fiat 128"

[19] "Honda Civic" "Toyota Corolla" "Toyota Corona"

[22] "Dodge Challenger" "AMC Javelin" "Camaro Z28"

[25] "Pontiac Firebird" "Fiat X1-9" "Porsche 914-2"

[28] "Lotus Europa" "Ford Pantera L" "Ferrari Dino"

[31] "Maserati Bora" "Volvo 142E"

```

So 'Mazda RX4' was the *name* of row 1, but not part of the row.

As with everything else, **row.names** is a function, and as you can see

above, its return value here is a 32-element vector (the data frame had

32 rows, thus 32 row names). The elements of that vector are of class

**'character'**, as is the vector itself.

You can even assign to that vector:

``` r

> row.names(mtcars)[7]

[1] "Duster 360"

> row.names(mtcars)[7] <- 'Dustpan'

> row.names(mtcars)[7]

[1] "Dustpan"

```

Inside joke, by the way. Yes, the example is real and significant, but

the "Dustpan" thing came from a funny TV commercial at the time.

(If you have some background in programming, it may appear odd to you to

have a function call on the *left* side of an assignment. This is

actually common in R. It stems from the fact that '<-' is actually a

function! But this is not the place to go into that.)

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> As a beginner (and for that matter later on), you should NOT be obsessed

> with always writing code in the "optimal" way, including in terms of

> compactness of the code. It's much more important

> to write something that works and is clear; one can always tweak it

> later. In this case, though, **tapply** actually aids clarity, and it

> is so ubiquitously useful that we have introduced it early in this

> tutorial. We'll be using it more in later lessons.

Most real-world data is "dirty," i.e. filled with errors. The famous

[New York taxi trip

dataset](https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Transportation/2017-Yellow-Taxi-Trip-Data/biws-g3hs),

for instance, has one trip destination whose lattitude and longitude

place it in Antartica! The impact of such erroneous data on one's statistical

analysis can be anywhere from mild to disabling. Let's see below how one

might ferret out bad data. And along the way, we'll cover several new R

concepts.

We'll use the famous Pima Diabetes dataset. Various versions exist, but

we'll use the one included in **faraway**, an R package compiled

by Julian Faraway, author of several popular books on statistical

regression analysis in R.

I've placed the data file, **Pima.csv**, on

[my Web site](http://heather.cs.ucdavis.edu/FasteR/data/Pima.csv). Here

is how you can read it into R:

``` r

> pima <- read.csv('http://heather.cs.ucdavis.edu/FasteR/data/Pima.csv',header=TRUE)

```

The dataset is in a CSV ("comma-separated values") file. Here we read

it, and assigned the resulting data frame to a variable we chose to name

**pima**.

Note that second argument, **header=TRUE**. A header in a file, if one

exists, is in the first line in the file. It states what names the

columns in the data frame are to have. If the file doesn't have one,

set **header** to FALSE. You can always add names to your data frame

later (future lesson).

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> It's always good to take a quick look at a newly loaded or construced

> data frame:

``` r

> head(pima)

pregnant glucose diastolic triceps insulin bmi diabetes age test

1 6 148 72 35 0 33.6 0.627 50 1

2 1 85 66 29 0 26.6 0.351 31 0

3 8 183 64 0 0 23.3 0.672 32 1

4 1 89 66 23 94 28.1 0.167 21 0

5 0 137 40 35 168 43.1 2.288 33 1

6 5 116 74 0 0 25.6 0.201 30 0

> dim(pima)

[1] 768 9

```

The **dim** function tells us that there are

768 people in the study, 9 variables measured on each, i.e. the data has

768 rows and 9 columns.

Since this is a study of diabetes, let's take a look at the glucose

variable. R's **table** function is quite handy.

``` r

> table(pima$glucose)

0 44 56 57 61 62 65 67 68 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81

5 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 3 4 1 3 4 2 2 2 4 3 6 6

82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101

3 6 10 7 3 7 9 6 11 9 9 7 7 13 8 9 3 17 17 9

102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121

13 9 6 13 14 11 13 12 6 14 13 5 11 10 7 11 6 11 11 6

122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141

12 9 11 14 9 5 11 14 7 5 5 5 6 4 8 8 5 8 5 5

142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161

5 6 7 5 9 7 4 1 3 6 4 2 6 5 3 2 8 2 1 3

162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181

6 3 3 4 3 3 4 1 2 3 1 6 2 2 2 1 1 5 5 5

182 183 184 186 187 188 189 190 191 193 194 195 196 197 198 199

1 3 3 1 4 2 4 1 1 2 3 2 3 4 1 1

```

Be careful here; the first, third, fifth and so on lines are the glucose

values, while the second, fourth, sixth and so on lines are the counts

of women having those values. For instance, 3 women had glucose = 68.

Uh, oh! 5 women in the study had glucose level 0. And 1 had level 44,

etc. Presumably 0 is not physiologically possible, and maybe not 44

either.

Let's consider a version of the glucose data that at least excludes these 0s.

``` r

> pg <- pima$glucose

> pg1 <- pg[pg > 0]

> length(pg1)

[1] 763

```

As before, the expression **pg > 0** creates a vector of TRUEs and FALSEs.

The filtering **pg[pg > 0]** will only pick up the TRUE cases, and sure

enough, we see that **pg1** has only 763 cases, as opposed to the

original 768; the 5 with glucose = 0 are now gone.

Did removing the 0s make much difference? Turns out it doesn't:

``` r

> mean(pg)

[1] 120.8945

> mean(pg1)

[1] 121.6868

```

But still, these things can in fact have major impact in many

statistical analyses.

R has a special code for missing values, NA, for situations like this.

Rather than removing the 0s, it's better to recode them as NAs. Let's

do this, back in the original dataset so we keep all the data in

one object:

``` r

> pima$glucose[pima$glucose == 0] <- NA

```

This is a bit complicated. Here is the same action, but broken into

smaller steps:

``` r

> glc <- pima$glucose

> z <- glc == 0

> glc[z] <- NA

> pima$glucose <- glc

```

Here is what the code does:

- That first line just makes a copy of the original vector, to avoid

clutter in the code.

- The second line determines which elements of **glc**

are 0s, resulting in **z** being a vector of TRUEs and FALSEs.

- The third line then assigns NA to those elements in **glc** corresponding to

the TRUEs. (Note the recycling of NA.)

- Finally, we need to have the changes in the original data, so we copy

**glc** to it.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> We broke our original 1 line of code into 4 simpler lines.

> This is MUCH clearer, and by the way, easier to debug.

> I recommend this especially for beginners, but also for everyone, and

> I use this approach a lot in my own code.

>

> There is an advanced R concept, *pipes*, that also breaks longer

> computations into smaller steps. I do not use pipes (either the

> Tidyverse version or the newer base-R pipes), as I believe they are

> less clear and, very important, hard to debug. You may find you like

> them, which of course is fine, but we will not use them here.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Note again the double-equal sign in the above code! If we wish to

> test whether, say, ***a*** and ***b*** are equal, the expression must

> be "a == b", not "a = b"; the latter would do "a <- b". This is a

> famous beginning programmer's error.

As a check, let's verify that we now have 5 NAs in the glucose variable:

``` r

> sum(is.na(pima$glucose))

[1] 5

```

Here the built-in R function **is.na** will return a vector of TRUEs and

FALSEs. Recall that those values can always be treated as 1s and 0s,

thus summable. Thus we got our count, 5.

Let's also check that the mean comes out right:

``` r

> mean(pima$glucose)

[1] NA

```

What went wrong? By default, the **mean** function will *not* skip over

NA values; thus the mean was reported as NA too. But we can instruct

the function to skip the NAs:

``` r

> mean(pima$glucose,na.rm=TRUE)

[1] 121.6868

```

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> Determine which other columns in **pima** have

> suspicious 0s, and replace them with NA values.

>

> Now, look again at the plot we made earlier of the Nile flow histogram.

> There seems to be a gap between the numbers at the low end and the rest.

> What years did these correspond to? Find the mean of the data,

> excluding these cases.

## Lesson 11: The R List Class

We saw earlier how handy the **tapply** function can be. Let's look at

a related one, **split**. The general call form of the latter is

``` r

split(what to split, what criterion to use for splitting)

```

This looks similar to the form for **tapply** that we saw earlier,

``` r

tapply(what to split, what criterion to use for splitting,

what to do with the resulting grouped data)

```

But this is no surprise, because the internal code for **tapply**

actually calls **split**. (You can check this via **edit(tapply)**; hit

ZZ to exit.)

Earlier we mentioned the built-in dataset **mtcars**, a data frame.

Consider **mtcars$mpg**, the column containing the miles-per-gallon

data. Again, to save typing and avoid clutter in our code, let's make a

copy first:

``` r

> mtmpg <- mtcars$mpg

```

Suppose we wish to split the original vector into three vectors,

one for 4-cylinder cars, one for 6 and one for 8. We *could* do

``` r

> mt4 <- mtmpg[mtcars$cyl == 4]

```

and so on for **mt6** and **mt8**.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> In order to keep up, make sure you understand how that

> line of code works, with the TRUEs and FALSEs etc. First print out the

> value of **mtcars$cyl == 4**, and go from there.

But there is a cleaner way:

``` r

> mtl <- split(mtmpg,mtcars$cyl)

> mtl

$`4`

[1] 22.8 24.4 22.8 32.4 30.4 33.9 21.5 27.3 26.0 30.4 21.4

$`6`

[1] 21.0 21.0 21.4 18.1 19.2 17.8 19.7

$`8`

[1] 18.7 14.3 16.4 17.3 15.2 10.4 10.4 14.7 15.5 15.2 13.3 19.2 15.8 15.0

> class(mtl)

[1] "list"

```

In English, the call to **split** said, "Split **mtmpg** into multiple

vectors, with the splitting criterion being the correspond

values in **mtcars$cyl**."

Now **mtl**, an object of R class **"list"**, contains the 3 vectors.

We can access them individually with the dollar sign notation:

``` r

> mtl$`4`

[1] 22.8 24.4 22.8 32.4 30.4 33.9 21.5 27.3 26.0 30.4 21.4

```

Or, we can use indices, though now with double brackets:

``` r

> mtl[[1]]

[1] 22.8 24.4 22.8 32.4 30.4 33.9 21.5 27.3 26.0 30.4 21.4

```

``` r

> mtl[[2]][1:3]

[1] 21.0 21.0 21.4

```

Looking a little closer:

``` r

> head(mtcars$cyl)

[1] 6 6 4 6 8 6

```

We see that the first car had 6 cylinders, so the

first element of **mtmpg**, 21.0, was thrown into the `6` pile, i.e.

**mtl[[2]]** (see above printout of **mtl**), and so on.

And of course we can make copies for later convenience:

``` r

> m4 <- mtl[[1]]

> m6 <- mtl[[2]]

> m8 <- mtl[[3]]

```

Lists are especially good for mixing types together in one package:

``` r

> l <- list(a = c(2,5), b = 'sky')

> l

$a

[1] 2 5

$b

[1] "sky"

```

Note that here we can give names to the list elements, 'a' and 'b'. In

forming **mtl** using **split** above, the names were assigned

according to the values of the vector beiing split. (In that earlier

case, we also needed backquotes `` ``, since the names were numbers.)

If we don't like those default names, we can change them:

``` r

> names(mtl) <- c('four','six','eight')

> mtl

$four

[1] 22.8 24.4 22.8 32.4 30.4 33.9 21.5 27.3 26.0 30.4 21.4

$six

[1] 21.0 21.0 21.4 18.1 19.2 17.8 19.7

$eight

[1] 18.7 14.3 16.4 17.3 15.2 10.4 10.4 14.7 15.5 15.2 13.3 19.2 15.8

15.0

```

What if we want, say, the MPG for the third car in the 6-cylinder

category?

``` r

> mtl[[2]][3]

[1] 21.4

```

The point is that **mtl[[2]]** is a vector, so if we want element 3 of

that vector, we tack on [3].

Or,

``` r

> mtl$six[3]

[1] 21.4

```

By the way, it's no coincidence that a dollar sign is used for

delineation in both data frames and lists; data frames *are* lists.

Each column is one element of the list. So for instance,

``` r

> mtcars[[1]]

[1] 21.0 21.0 22.8 21.4 18.7 18.1 14.3 24.4 22.8 19.2 17.8 16.4 17.3 15.2 10.4

[16] 10.4 14.7 32.4 30.4 33.9 21.5 15.5 15.2 13.3 19.2 27.3 26.0 30.4 15.8 19.7

[31] 15.0 21.4

```

Here we used the double-brackets list notation to get the first element

of the list, which is the first column of the data frame.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> In the **mtcars** data, write code to do the following (individually,

> separate code for each):

>

> * Print out the 5th through 8th values for horsepower in 4-cylinder

> cars.

>

> * Print the *last* 3 values in MPG for 6-cylinder cars. This should be

> done fully *programmatically*, i.e. without your setting values by

> had. Make use of the **length** function.

>

> * Find the average horsepower among all cars in the dataset.

>

> * One can divide one vector by another, e.g. c(6,12,25) / c(3,2,5)

> will produce c(2,6,5). Write code that first computes the vector of

> horsepower-to-weight ratios, and then computes their average.

> (Warning: This is *not* the same as average horsepower divided by

> average weight.)

## Lesson 12: Another Look at the Nile Data

Here we'll learn several new concepts, using the **Nile** data as our

starting point.

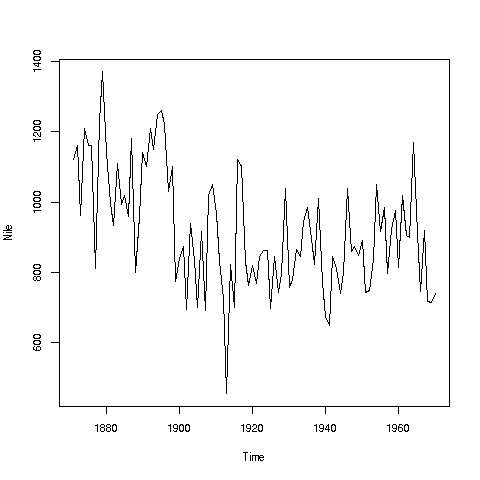

If you look again at the histogram of the Nile we generated, you'll see

a gap between the lowest numbers and the rest. In what year(s) did

those really low values occur? Let's plot the data against time:

``` r

> plot(Nile)

```

Looks like maybe 1912 or so was much lower than the rest. Is this an

error? Or was there some big historical event then? This would require

more than R to track down, but at least R can tell us which exact year or

years correspond to the unusually low flow. Here is how:

We see from the graph that the unusually low value was below 600. We

can use R's **which** function to see when that occurred:

``` r

> which(Nile < 600)

[1] 43

```

As before, make sure to understand what happened in this code. The

expression **Nile < 600** yields 100 TRUEs and FALSEs. The **which**

then tells us which of those were TRUEs.

So, element 43 is the culprit here, corresponding to year 1871+42=1913.

Again, we would have to find supplementary information in order to

decide whether this is a genuine value or an error, but at least now we

know the exact year.

Of course, since this is a small dataset, we could have just printed out the

entire data and visually scanned it for a low number. But what if the

length of the data vector had been 100,000 instead of 100? Then the

visual approach wouldn't work.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Remember, a goal of programming is to automate tasks, rather

> than doing them by hand.

> ❄️ Your Turn

>

> There appear to be some unusually high values as well,

> e.g. one around 1875. Determine which year this was, using the

> techniques presented here.

>

> Also, try some similar analysis on the

> built-in **AirPassengers** data. Can you guess why those peaks are

> occurring?

>

> Call **hist()** on the **AirPassengers** data, but save the return

> value in a variable **z**. The latter is technically of class

> **histogram**, but is essentially an R list. Type 'str(z)' to see

> what's in it, and write code to find the mean value of the bin counts.

> (Note that this does NOT mean copying the numbers by hand; it should

> be all code.)

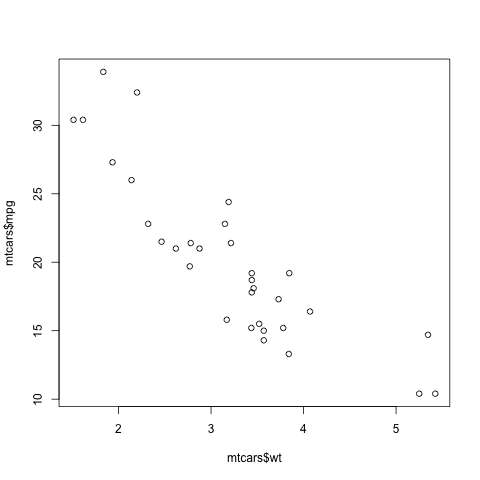

Here is another point: That function **plot** is not quite so innocuous

as it may seem. Let's run the same function, **plot**, but with two

arguments instead of one:

``` r

> plot(mtcars$wt,mtcars$mpg)

```

In contrast to the previous plot, in which our data were on the vertical

axis and time was on the horizontal, now we are plotting *two* vectors,

against each other. This enables us to explore the relation between

car weight and gas mileage.

There are a couple of important points here. First, as we might guess,

we see that the heavier cars tended to get poorer gas mileage. But

here's more: That **plot** function is pretty smart!

Why? Well, **plot** knew to take different actions for different input

types. When we fed it a single vector, it plotted those numbers against

time (or, against index). When we fed it two vectors, it knew to do a scatter plot.

In fact, **plot** was even smarter than that. It noticed that **Nile**

is not just of **'numeric'** type, but also of another class, **'ts'**

("time series"):

``` r

> is.numeric(Nile)

[1] TRUE

> class(Nile)

[1] "ts"

```

So, **plot** put years on the horizontal axis, instead of indices 1,2,3,...

And one more thing: Say we wanted to know the flow in the year 1925.

The data start at 1871, so 1925 is 1925 - 1871 = 54 years later. Since

the 1871 number is in element 1 of the vector, that means the flow for

the year 1925 is in element 1+54 = 55.

``` r

> Nile[55]

[1] 698

```

OK, but why did we do this arithmetic ourselves? We should have R do

it:

``` r

> Nile[1 + 1925 - 1871]

[1] 698

```

R did the computation 1925 - 1871 + 1 itself, yielding 55, then looked

up the value of **Nile[55]**. This is the start of your path to

programming -- we try to automate things as much as possible, doing

things by hand as little as possible.

## Lesson 13: Pause to Reflect

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Repeating an earlier point:

> How does one build a house? There of course is no set formula. One has

> various tools and materials, and the goal is to put these together in a

> creative way to produce the end result, the house.

>

> It's the same with R. The tools here are the various functions, e.g.

> **mean** and **which**, and the materials are one's data. One then must

> creatively put them together to achieve one's goal, say ferreting out

> patterns in ridership in a public transportation system. Again, it is a

> creative process; there is no formula for anything. But that is what

> makes it fun, like solving a puzzle.

>

> And...we can combine various functions in order to build *our own*

> functions. This will come in future lessons.

## Lesson 14: Introduction to Base R Graphics

One of the greatest things about R is its graphics capabilities. There

are excellent graphics features in base R, and then many contributed

packages, with the best known being **ggplot2** and **lattice**. These

latter two are quite powerful, and will be the subjects of future

lessons, but for now we'll concentrate on the base.

As our example here, we'll use a dataset I compiled on Silicon Valley

programmers and engineers, from the US 2000 census. Let's read

in the data and take a look at the first records:

``` r

> load(url(

'https://github.com/matloff/fasteR/blob/master/data/prgeng.RData?raw=true'))

> head(prgeng)

age educ occ sex wageinc wkswrkd

1 50.30082 13 102 2 75000 52

2 41.10139 9 101 1 12300 20

3 24.67374 9 102 2 15400 52

4 50.19951 11 100 1 0 52

5 51.18112 11 100 2 160 1

6 57.70413 11 100 1 0 0

```

Here we use **load** to input the data, which was stored in R's

compressed form. This function will be explained in [Lesson

16](#less10), but for now, the point is that this was necessary to

preserve the R factor structure of some of the variables.

Here **educ** and **occ** are codes, for levels of education and

different occupations. For now, let's not worry about the specific

codes. (You can find them in the

[Census Bureau document](https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2000/doc/pums.pdf).

For instance, search for "Educational Attainment" for the **educ**

variable.)

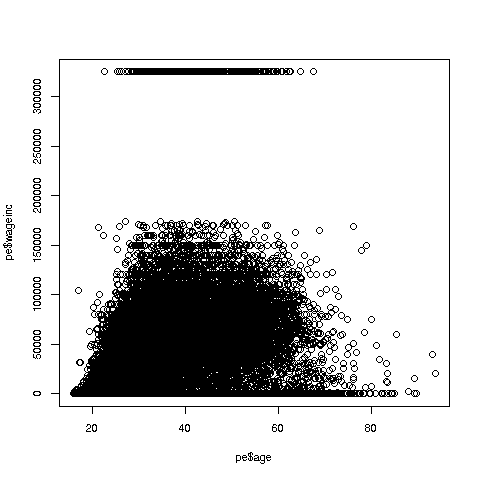

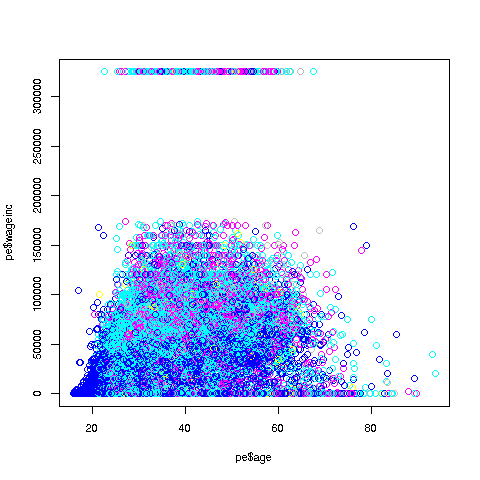

Let's start with a scatter plot of wage vs. age:

``` r

> plot(prgeng$age,prgeng$wageinc)

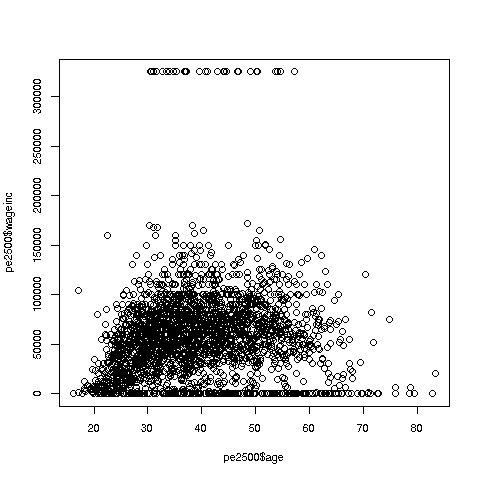

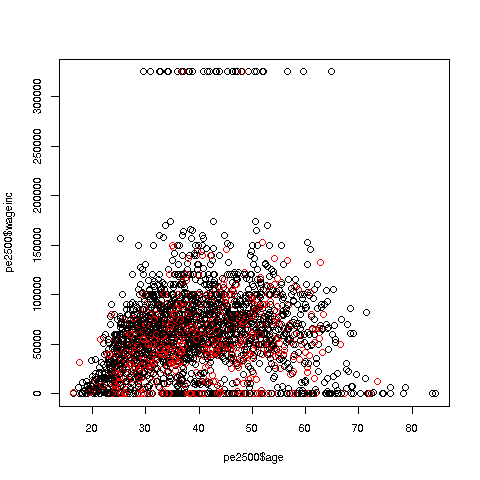

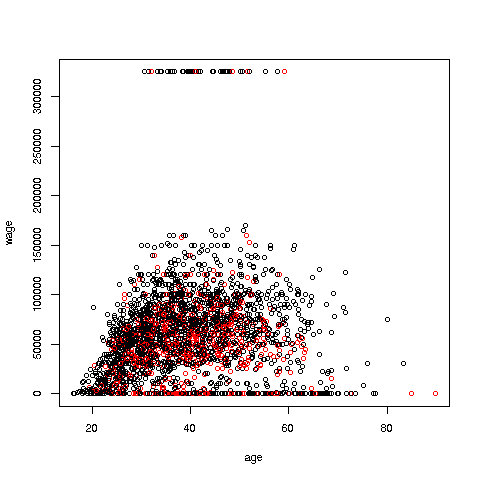

```

Oh no, the dreaded Black Screen Problem! There are about 20,000 data

points, thus filling certain parts of the screen. So, let's just plot a

random sample, say 2500. (There are other ways of handling the problem,

say with smaller dots or *alpha blending*.)

``` r

> rowNumbers <- sample(1:nrow(prgeng),2500)

> prgeng2500 <- prgeng[rowNumbers,]

```

Recall that the **nrow** function returns the number of rows in the

argument, which in this case is 20090, the number of rows in **prgeng**.

R's **sample** function does what its name implies. Here it randomly

samples 2500 of the numbers from 1 to 20090. We then extracted those

rows of **prgeng**, in a new data frame **prgeng2500**.

> 📘 Pro Tip

>

> Note again that it's usually clearer to break complex operations into

> simpler, smaller ones. I could have written the more compact

>

> ``` r

> > prgeng2500 <- prgeng[sample(1:nrow(prgeng),2500),]

> ```

>

> but it would be hard to read that way. I also use direct function

> composition sparingly, preferring to break

>

> ``` r

> h(g(f(x),3)

> ```

>

> into

>

> ``` r

> y <- f(x)

> z <- g(y,3)

> h(z)

> ```

>

> (As noted earlier, my personal view is that pipes, though also breaking

> complex statements into smaller ones, is less clear and harder to debug,

> so I don't use them.)

So, here is the new plot:

``` r

> plot(prgeng2500$age,prgeng2500$wageinc)

```

Note that since I plotted a random sample of rows, the ones you get may

differ from the ones I got. The resulting graph will be largely similar

but probably not identical.

OK, now we are in business. A few things worth noting:

* The relation between wage and age is not linear, indeed not even

monotonic. After the early 40s, one's wage tends to decrease. As with

any observational dataset, the underlying factors are complex, but it

does seem there is an age discrimination problem in Silicon Valley.

(And it is well documented in various studies and litigation.)

* Note the horizontal streaks at the very top and very bottom of the

picture. Some people in the census had 0 income (or close to it), as

they were not working. And the census imposed a top wage limit of

$350,000 (probably out of privacy concerns), so that higher numbers were

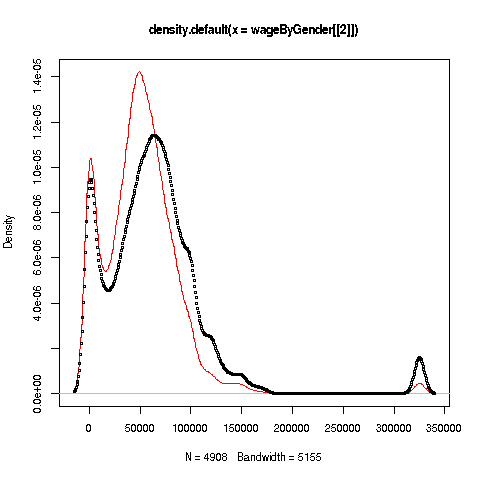

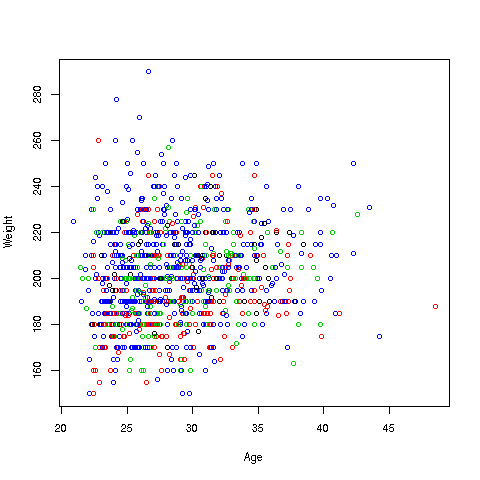

truncated to that value.