https://github.com/rustyconover/duckdb-lindel-extension

DuckDB Extension Linearization/Delinearization, Z-Order, Hilbert and Morton Curves

https://github.com/rustyconover/duckdb-lindel-extension

duckdb duckdb-extension hilbert hilbert-curve hilbert-transform linearization morton morton-order space-filling-curves zorder-curves

Last synced: 9 months ago

JSON representation

DuckDB Extension Linearization/Delinearization, Z-Order, Hilbert and Morton Curves

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/rustyconover/duckdb-lindel-extension

- Owner: rustyconover

- License: mit

- Created: 2024-06-29T19:55:08.000Z (over 1 year ago)

- Default Branch: main

- Last Pushed: 2025-02-15T10:51:09.000Z (10 months ago)

- Last Synced: 2025-03-19T20:59:34.663Z (9 months ago)

- Topics: duckdb, duckdb-extension, hilbert, hilbert-curve, hilbert-transform, linearization, morton, morton-order, space-filling-curves, zorder-curves

- Language: C++

- Homepage:

- Size: 277 KB

- Stars: 40

- Watchers: 2

- Forks: 4

- Open Issues: 0

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

- awesome-duckdb - `lindel` - Linearization/Delinearization, Z-Order, Hilbert and Morton Curves. (Extensions / [Community Extensions](https://duckdb.org/community_extensions/))

README

# Lindel (linearizer-delinearizer) Extension for DuckDB

This `lindel` extension adds functions for the [linearization](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linearization) and delinearization of numeric arrays in [DuckDB](https://www.duckdb.org). It allows you to order multi-dimensional data using space-filling curves.

## Installation

**`lindel` is a [DuckDB Community Extension](https://github.com/duckdb/community-extensions).**

You can now use this by using this SQL:

```sql

install lindel from community;

load lindel;

```

## What is linearization?

[Linearization](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linearization) maps multi-dimensional data into a one-dimensional sequence while [preserving locality](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locality_of_reference), enhancing the efficiency of data structures and algorithms for spatial data, such as in databases, GIS, and memory caches.

> "The principle of locality states that programs tend to reuse data and instructions they have used recently."

In SQL, sorting by a single column (e.g., time or identifier) is often sufficient, but sometimes queries involve multiple fields, such as:

- Time and identifier (historical trading data)

- Latitude and Longitude (GIS applications)

- Latitude, Longitude, and Altitude (flight tracking)

- Latitude, Longitude, Altitude, and Time (flight history)

Sorting by a single field isn't optimal for multi-field queries. Linearization maps multiple fields into a single value, while preserving locality—meaning values close in the original representation remain close in the mapped representation.

#### Where has this been used before?

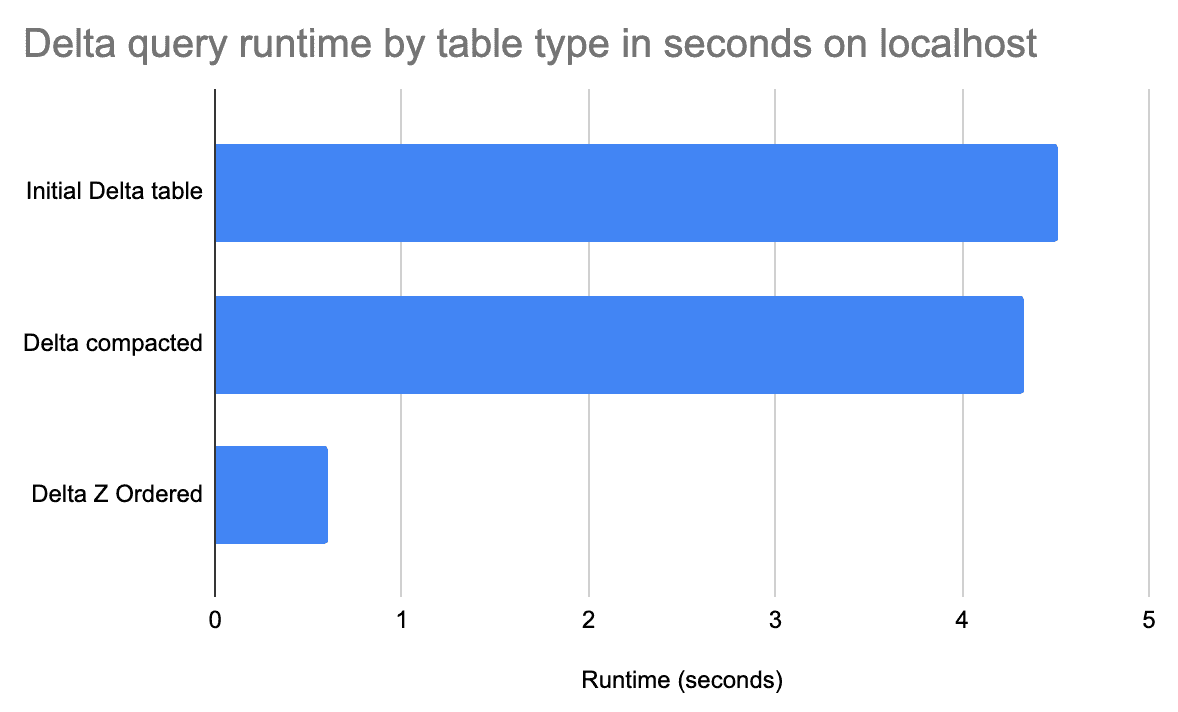

DataBricks has long supported Z-Ordering (they also now default to using the Hilbert curve for the ordering). This [video explains how Delta Lake queries are faster when the data is Z-Ordered.](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1aR1A8OwOU) This extension also allows DuckDB to write files with the same ordering optimization.

Numerous articles describe the benefits of applying a Z-Ordering/Hilbert ordering to data for query performance.

- [https://delta.io/blog/2023-06-03-delta-lake-z-order/](https://delta.io/blog/2023-06-03-delta-lake-z-order/)

- [https://blog.cloudera.com/speeding-up-queries-with-z-order/](https://blog.cloudera.com/speeding-up-queries-with-z-order/)

- [https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/z-order-visualization-implementation-nick-karpov/](https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/z-order-visualization-implementation-nick-karpov/)

From one of the articles:

Your particular performance improvements will vary, but for some query patterns Z-Ordering and Hilbert ordering will make quite a big difference.

## When would I use this?

For query patterns across multiple numeric or short text columns, consider sorting rows using Hilbert encoding when storing data in Parquet:

```sql

COPY (

select * from 'source.csv'

order by

hilbert_encode([source_data.time, source_data.symbol_id]::integer[2])

)

TO 'example.parquet' (FORMAT PARQUET)

-- or if dealing with latitude and longitude

COPY (

select * from 'source.csv'

order by

hilbert_encode([source_data.lat, source_data.lon]::double[2])

) TO 'example.parquet' (FORMAT PARQUET)

```

The Parquet file format stores statistics for each row group. Since rows are sorted with locality into these row groups the query execution may be able to skip row groups that contain no relevant rows, leading to faster query execution times.

## Encoding Types

This extension offers two different encoding types, [Hilbert](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilbert_curve) and [Morton](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Z-order_curve) encoding.

### Hilbert Encoding

Hilbert encoding uses the Hilbert curve, a continuous fractal space-filling curve named after [David Hilbert](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hilbert). It rearranges coordinates based on the Hilbert curve's path, preserving spatial locality better than Morton encoding.

This is a great explanation of the [Hilbert curve](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3s7h2MHQtxc).

### Morton Encoding (Z-order Curve)

Morton encoding, also known as the Z-order curve, interleaves the binary representations of coordinates into a single integer. It is named after Glenn K. Morton.

**Locality:** Hilbert encoding generally preserves locality better than Morton encoding, making it preferable for applications where spatial proximity matters.

## API

### Encoding

**Supported types:** Any signed or unsigned integer, float, or double (`INPUT_TYPE`).

**Output:** The smallest unsigned integer type that can represent the input array.

### Encoding Functions

* `hilbert_encode(ARRAY[INPUT_TYPE, 1-16])`

* `morton_encode(ARRAY[INPUT_TYPE, 1-16])`

Output is limited to a 128-bit `UHUGEINT`. The input array size is validated to ensure it fits within this limit.

| Input Type | Maximum Number of Elements | Output Type (depends on number of elements) |

|---|--|-------------|

| `UTINYINT` | 16 | 1: `UTINYINT`

2: `USMALLINT`

3-4: `UINTEGER`

4-8: `UBIGINT`

8-16: `UHUGEINT`|

| `USMALLINT` | 8 | 1: `USMALLINT`

2: `UINTEGER`

3-4: `UBIGINT`

4-8: `UHUGEINT` |

| `UINTEGER` | 4 | 1: `UINTEGER`

2: `UBIGINT`

3-4: `UHUGEINT` |

| `UBIGINT` | 2 | 1: `UBIGINT`

2: `UHUGEINT` |

| `FLOAT` | 4 | 1: `UINTEGER`

2: `UBIGINT`

3-4: `UHUGEINT` |

| `DOUBLE` | 2 | 1: `UBIGINT`

2: `UHUGEINT` |

### Encoding examples

```sql

install lindel from community;

load lindel;

with elements as (

select * as id from range(3)

)

select

a.id as a,

b.id as b,

hilbert_encode([a.id, b.id]::tinyint[2]) as hilbert,

morton_encode([a.id, b.id]::tinyint[2]) as morton

from

elements as a cross join elements as b;

┌───────┬───────┬─────────┬────────┐

│ a │ b │ hilbert │ morton │

│ int64 │ int64 │ uint16 │ uint16 │

├───────┼───────┼─────────┼────────┤

│ 0 │ 0 │ 0 │ 0 │

│ 0 │ 1 │ 3 │ 1 │

│ 0 │ 2 │ 4 │ 4 │

│ 1 │ 0 │ 1 │ 2 │

│ 1 │ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │

│ 1 │ 2 │ 7 │ 6 │

│ 2 │ 0 │ 14 │ 8 │

│ 2 │ 1 │ 13 │ 9 │

│ 2 │ 2 │ 8 │ 12 │

└───────┴───────┴─────────┴────────┘

-- Now sort that same table using Hilbert encoding

┌───────┬───────┬─────────┬────────┐

│ a │ b │ hilbert │ morton │

│ int64 │ int64 │ uint16 │ uint16 │

├───────┼───────┼─────────┼────────┤

│ 0 │ 0 │ 0 │ 0 │

│ 1 │ 0 │ 1 │ 2 │

│ 1 │ 1 │ 2 │ 3 │

│ 0 │ 1 │ 3 │ 1 │

│ 0 │ 2 │ 4 │ 4 │

│ 1 │ 2 │ 7 │ 6 │

│ 2 │ 2 │ 8 │ 12 │

│ 2 │ 1 │ 13 │ 9 │

│ 2 │ 0 │ 14 │ 8 │

└───────┴───────┴─────────┴────────┘

-- Do you notice how when A and B are closer to 2 the rows are "closer"?

```

Encoding doesn't only work with integers it can also be used with floats.

```sql

install lindel from community;

load lindel;

-- Encode two 32-bit floats into one uint64

select hilbert_encode([37.8, .2]::float[2]) as hilbert;

┌─────────────────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint64 │

├─────────────────────┤

│ 2303654869236839926 │

└─────────────────────┘

-- Since doubles use 64 bits of precision the encoding

-- must result in a uint128

select hilbert_encode([37.8, .2]::double[2]) as hilbert;

┌────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint128 │

├────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 42534209309512799991913666633619307890 │

└────────────────────────────────────────┘

-- 3 dimensional encoding.

select hilbert_encode([1.0, 5.0, 6.0]::float[3]) as hilbert;

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint128 │

├──────────────────────────────┤

│ 8002395622101954260073409974 │

└──────────────────────────────┘

```

Not to be left out you can also encode strings.

```sql

select hilbert_encode([ord(x) for x in split('abcd', '')]::tinyint[4]) as hilbert;

┌───────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint32 │

├───────────┤

│ 178258816 │

└───────────┘

--- This splits the string 'abcd' by character, then converts each character into

--- its ordinal representation, finally converts them all to 8 bit integers and then

--- performs encoding.

```

Currently, the input for `hilbert_encode()` and `morton_encode()` functions in DuckDB requires that all elements in the input array be of the same size. If you need to encode different-sized types, you must break up larger data types into units of the smallest data type. Results may vary.

### Decoding Functions

* `hilbert_encode(ANY_UNSIGNED_INTEGER_TYPE, TINYINT, BOOLEAN, BOOLEAN)`

* `morton_encode(ANY_UNSIGNED_INTEGER_TYPE, TINYINT, BOOLEAN, BOOLEAN)`

The decoding functions take four parameters:

1. **Value to be decoded:** This is always an unsigned integer type.

2. **Number of elements to decode:** This is a `TINYINT` specifying how many elements should be decoded.

3. **Float return type:** This `BOOLEAN` indicates whether the values should be returned as floats (REAL or DOUBLE). Set to true to enable this.

4. **Unsigned return type:** This `BOOLEAN` indicates whether the values should be unsigned if not using floats.

The return type of these functions is always an array, with the element type determined by the number of elements requested and whether "float" handling is enabled by the third parameter.

### Examples

```sql

-- Start out just by encoding two values.

select hilbert_encode([1, 2]::tinyint[2]) as hilbert;

┌─────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint16 │

├─────────┤

│ 7 │

└─────────┘

D select hilbert_decode(7::uint16, 2, false, true) as values;

┌─────────────┐

│ values │

│ utinyint[2] │

├─────────────┤

│ [1, 2] │

└─────────────┘

-- Show that the decoder works with the encoder.

select hilbert_decode(hilbert_encode([1, 2]::tinyint[2]), 2, false, false) as values;

┌─────────────┐

│ values │

│ utinyint[2] │

├─────────────┤

│ [1, 2] │

└─────────────┘

-- FIXME: need to implement a signed or unsigned flag on the decoder function.

select hilbert_decode(hilbert_encode([1, -2]::bigint[2]), 2, false, false) as values;

┌───────────┐

│ values │

│ bigint[2] │

├───────────┤

│ [1, -2] │

└───────────┘

select hilbert_encode([1.0, 5.0, 6.0]::float[3]) as hilbert;

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint128 │

├──────────────────────────────┤

│ 8002395622101954260073409974 │

└──────────────────────────────┘

select hilbert_decode(8002395622101954260073409974::UHUGEINT, 3, True, False) as values;

┌─────────────────┐

│ values │

│ float[3] │

├─────────────────┤

│ [1.0, 5.0, 6.0] │

└─────────────────┘

```

## Credits

1. This DuckDB extension utilizes and is named after the [`lindel`](https://crates.io/crates/lindel) Rust crate created by [DoubleHyphen](https://github.com/DoubleHyphen).

2. It also uses the [DuckDB Extension Template](https://github.com/duckdb/extension-template).

3. This extension uses [Corrosion](https://github.com/corrosion-rs/corrosion) to combine CMake with a Rust/Cargo build process.

4. I've gotten a lot of help from the generous DuckDB developer community.

### Build Architecture

For the DuckDB extension to call the Rust code a tool called `cbindgen` is used to write the C++ headers for the exposed Rust interface.

The headers can be updated by running `make rust_binding_headers`.

#### Building on MacOS X

Example setup + build steps for macOS users:

```sh

# Remove rust if previously installed via brew

brew uninstall rust

# Install rustup + cbindgen

# (use rustup to switch versions of Rust without extra fuss)

brew install cbindgen rustup

rustup toolchain install stable

# Initialize rustup

# Zsh users: customize installation, answer n to "Modify PATH variable?",

# and continue with defaults for everything else

rustup-init

# OPTIONAL step for zsh users: add rust + cargo env setup to zshrc:

echo '. "$HOME/.cargo/env"' >> ~/.zshrc

# Use rustc stable version by default

rustup default stable

# Build headers

make rust_binding_headers

GEN=ninja make

```

### Build steps

Now to build the extension, run:

```sh

make

```

The main binaries that will be built are:

```sh

./build/release/duckdb

./build/release/test/unittest

./build/release/extension/lindel/lindel.duckdb_extension

```

- `duckdb` is the binary for the duckdb shell with the extension code automatically loaded.

- `unittest` is the test runner of duckdb. Again, the extension is already linked into the binary.

- `lindel.duckdb_extension` is the loadable binary as it would be distributed.

## Running the extension

To run the extension code, simply start the shell with `./build/release/duckdb`.

Now we can use the features from the extension directly in DuckDB.

```

D select hilbert_encode([1.0, 5.0, 6.0]::float[3]) as hilbert;

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ hilbert │

│ uint128 │

├──────────────────────────────┤

│ 8002395622101954260073409974 │

└──────────────────────────────┘

```

## Running the tests

Different tests can be created for DuckDB extensions. The primary way of testing DuckDB extensions should be the SQL tests in `./test/sql`. These SQL tests can be run using:

```sh

make test

```

### Installing the deployed binaries

To install your extension binaries from S3, you will need to do two things. Firstly, DuckDB should be launched with the

`allow_unsigned_extensions` option set to true. How to set this will depend on the client you're using. Some examples:

CLI:

```shell

duckdb -unsigned

```

Python:

```python

con = duckdb.connect(':memory:', config={'allow_unsigned_extensions' : 'true'})

```

NodeJS:

```js

db = new duckdb.Database(':memory:', {"allow_unsigned_extensions": "true"});

```

Secondly, you will need to set the repository endpoint in DuckDB to the HTTP url of your bucket + version of the extension

you want to install. To do this run the following SQL query in DuckDB:

```sql

SET custom_extension_repository='bucket.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/lindel/latest';

```

Note that the `/latest` path will allow you to install the latest extension version available for your current version of

DuckDB. To specify a specific version, you can pass the version instead.

After running these steps, you can install and load your extension using the regular INSTALL/LOAD commands in DuckDB:

```sql

INSTALL lindel

LOAD lindel

```