Ecosyste.ms: Awesome

An open API service indexing awesome lists of open source software.

https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2

Experiment with hot swapping pipelined state machines

https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2

Last synced: 9 days ago

JSON representation

Experiment with hot swapping pipelined state machines

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2

- Owner: stevana

- License: bsd-2-clause

- Created: 2024-02-03T14:33:52.000Z (9 months ago)

- Default Branch: main

- Last Pushed: 2024-03-07T13:30:50.000Z (8 months ago)

- Last Synced: 2024-03-08T10:58:17.037Z (8 months ago)

- Language: Haskell

- Homepage:

- Size: 325 KB

- Stars: 1

- Watchers: 1

- Forks: 0

- Open Issues: 0

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- Changelog: CHANGELOG.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

# Towards zero-downtime upgrades of stateful systems

## Motivation

Most deployed programs need to be upgraded at some point. The reasons vary from

adding new features to patching a bug and potentially fixing a broken state.

Even though upgrades are an essential part of software development and

maintenance, programming languages tend to not help the programmer deal with

them in any way.

The situation reminds me of a remark made by Barbara Liskov about deployment of

software (which is related to upgrades) in her Turing award

[lecture](https://youtu.be/qAKrMdUycb8?t=3058) (2009):

> "There’s a funny disconnect in how we write distributed programs. You write

> your individual modules, but then when you want to connect them together

> you’re out of the programming language and into this other world. Maybe we

> need languages that are a little bit more complete now, so that we can write

> the whole thing in the language."

There's one exception, that I know of, where upgrades are talked about from

within the language: Erlang/OTP. In OTP there's a library construct called

[*release*](https://www.erlang.org/doc/design_principles/release_structure),

which can be used to perform up- and downgrades. Furthermore, these up- and

downgrades can hot swap the running code resulting in zero-downtime and no

interruption of the service of connected clients.

If you haven't seen Erlang's hot swapping feature before, then you might want to

have a look at the classic [Erlang the

movie](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xrIjfIjssLE), which contains a

telecommunications example of this. If you prefer reading over watching, then

I've written an earlier

[post](https://stevana.github.io/hot-code_swapping_a_la_erlang_with_arrow-based_state_machines.html)

which starts off by explaining a REPL session which performs an upgrade (my

example isn't nearly as cool as in the movie though).

What is it that Erlang's releases and hot swapping facilities do? Can we steal

those ideas and build upon them? These are the main questions that motivated me

in writing this post.

Let's take a step back, ignoring Erlang for a moment, and ask ourselves: what

would good support for upgrades look like?

* Zero-downtime: seamless, don't interrupt existing client connections or

sessions;

* If there's any state then migrate it in a type-safe way;

* Backwards and forwards compatibility: old clients should be able to talk to

newer servers, and newer clients should be able to talk to old servers;

* Atomicity: upgrades either succeed, or fail and rollback any changes;

* Downgrades: even if an upgrade succeeds we might want to rollback to an

earlier version.

In the rest of this post I'd like to explore how we can achieve some of this.

## Terminology

Having defined some desirable characteristics of upgrades, let's move on to

defining what we mean by upgrades.

There are two notions I'd like clarify: what kind of software systems the

upgrades are targeting, and then how we represent programs and their upgrades.

### Software systems

There's different kinds of software systems one might want to upgrade.

1. Client-only, e.g. a compiler, editor, or some command line utility which

runs locally on your computer and doesn't interact with any server.

Downtime is typically not a problem, and the state of the program is

typically saved to disk. The operating system's package manager typically

takes care of the upgrades, with minimal user involvement. However there

are situations where one might like to perform an upgrade without first

terminating the old version of a client-only application, e.g. the

fix-and-continue debugging

[workflow](https://lispcookbook.github.io/cl-cookbook/debugging.html#resume-a-program-execution-from-anywhere-in-the-stack)

from Lisp and Smalltalk, [live coding

music](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TidalCycles), or when working with

large data sets, e.g. in

[bioinformatics](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1386713/);

2. Client-server applications where the target of the upgrade is a *stateless*

component of the server, e.g. a front-end or a REST API. The stateless

components typically retrieve the state they need to service a request from

a stateful component, e.g. a database, but they don't maintain any state of

their own, which makes stateless components easier to upgrade. A common

strategy is to stick a load balancer in-front of the stateless

component(s), spin up the new version of the component while keeping the

old version around, and then (slowly) migrate traffic over to the new

version. Notice that this wouldn't necessarily work if there was state in

the components, as then the state of the old and new versions of the

components might diverge and potentially have unexpected results;

3. Client-server applications where the target of the upgrade is a *stateful*

component of the server, e.g. a database or a service with a stateful

protocol like FTP. Databases were designed for supporting upgrades, with

features like schema migrations and replication. The high-level idea would

be to spin up the new version, take a snapshot of the old database, start

logically replicating all new requests from the old to the new database

while also restoring the snapshot to the new database, once the new

database has caught up, we can switch over and tear down the old database.

Depending on the volume of the database and the rate of new traffic this

can still be a difficult operation.

A service like FTP, where once the user is connected they can "move around"

by e.g. changing the working directory and list the contents of the current

working directory, are typically not possible to upgrade without downtime.

The problem is that the response of one command depends on the history of

previous commands in that user sessions, and this state is transient. If

you think FTP is a silly protocol (it's), then consider the similarly

stateful POSIX filesystem API, with its file handles that can be opened,

read, written, and closed;

4. Distributed stateful systems, e.g. a distributed key-value database. This

is similar to the above, but the replication of data is performed all the

time rather than only at the moment an upgrade is performed. The

disadvantage is that we need more hardware and bandwidth, but on the other

hand it makes upgrades much easier. Distributed systems can typically

tolerate and repair some amount of faulty replicas, which allows for

rolling upgrades where we replace one of the server components at the time;

5. There's also [local-first](https://www.inkandswitch.com/local-first/)

systems, which are different to all the above. I've not had a chance to think

about upgrades in that context, so I won't talk about them any further.

In this post I'd like to focus on upgrading stateful systems, like

non-distributed databases and stateful services like FTP or filesystems.

Stateful systems arguably have the worst upgrade path of the ones listed above,

making them more interesting to work on. That said I hope that the techniques

can be used to simplify upgrades in the other kinds of systems too, and

potentially enabling other possibilities like better debugging experience and

live coding.

### Programs and their upgrades

Having defined what kind of systems we'd like to upgrade, let's turn our

attention to how we can represent programs and their upgrades.

We could choose to use the syntax of a specific programming language to

represent programs, but programming languages tend to be too big and

complicated. Or, we could be general and represent programs as λ-calculus terms

or equivalently Turing machines, but that would be too clumsy and too low-level.

A happy middle ground, which is easy to implement in any programming language

while at the same time expressive enough to express any algorithm at a desired

level of abstraction, is the humble state machine[^1]. There are different ways

to define state machines, we'll go for a definition which is a simple function

from some input and a state to a pair of some output and a new state:

```

input -> state -> (state, output)

```

where inputs, states and outputs are algebraic datatypes (records/structs and

tagged unions).

To make things concrete, let's consider an example where we represent a counter

as a state machine. One way to define such a state machine is to use the enum

`{ReadCount, IncrCount}` as input, set the state to be an integer and the output

to be a tagged union where in the read case we return an integer and in the

increment case we return an acknowledgment (unit or void type). Given these

types, the state machine function of the counter can be defined as follows (in

Python):

```python

def counter(input: Input, state: int) -> (int, int | None):

match input:

case Input.ReadCount: return (state, state)

case Input.IncrCount: return (state + 1, None)

```

Assuming our programs are such state machines, what would it mean to upgrade

them? I think this is where having a simple representation of programs where all

of the state is explicit starts to shine. By merely looking at the function type

of a state machine, we can see that it would make sense to be able to:

1. Extend the input type with more cases, e.g. a `ResetCount` which sets the

new state to `0`;

2. Refine an existing output with more data, e.g. we could return the old

count when we increment;

3. Extending the state, e.g. we could add a boolean to the state which

determines if we should increment by +1 or -1 (i.e. decrementing);

4. Refine an existing input, e.g. make `IncrCount` have an integer value

associated with it which determines by how much we want to increment.

I don't know if the above list complete, but it's a start.

If we go back to the list of criteria for good upgrade support, we can see how

some of the items there are more tangible now.

For example, typed state migrations means that if we change the state type from

`state` to `state'` then when we migrate to old to the new state using a

function of type `state -> state'`.

Similarly, what it means to support backwards compatibility is more clear now.

Imagine we upgrade from a server state machine:

```

input -> state -> (output, state)

```

to a new version that has the following type:

```

input' -> state' -> (output', state')

```

What would it take to still be able to serve old clients which make requests

using the old `input` type? If we had a function from `input -> input'` we could

upgrade the request, feed it to the new state machine and get an `output'` back,

we then see that we'd also need a way to downgrade the output, i.e. a function

`output' -> output`[^2].

Forward compatibility, i.e. an upgraded client sends an `input'` to a server

which haven't been upgraded yet (i.e. expects `input`), is a bit more tricky,

but again at least we can now start to be able to talk about these things in a

more concrete way.

One last thing with regard to how to represent programs. Our state machines run

entirely sequentially, which is a problem if we want to implement servers that

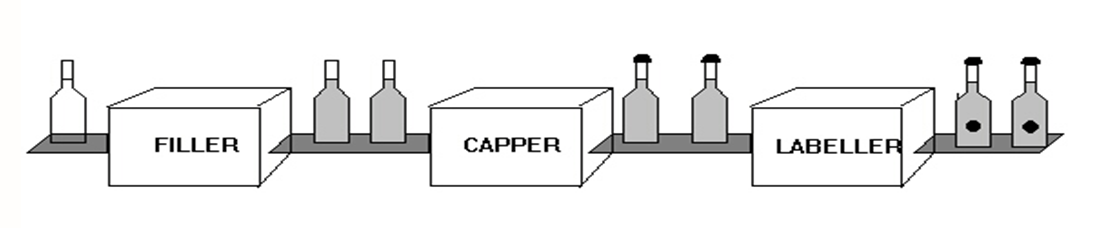

can handle more than one client at the time. A simple way adding parallelism is

make it possible to construct pipelines of state machines, where the state

machines run in parallel. Picture the state machines as processing stages on a

conveyor belt.

The conveyor belt in our case, i.e. our pipeline, will be queues which connect

the state machines.

A typical TCP-based service can then be composed of a pipeline that:

1. Accepts new connections/sockets from a client;

2. Waits for some of the accepted sockets to be readable (this requires some

`select/poll/io_uring`-like constructs);

3. `recv` the bytes of a request;

4. Deserialise the request bytes into an input;

5. Process the input using the a state machine to produce an output

(potentially reading and writing to disk);

6. Serialise the output into a response in bytes;

7. Wait for the socket to be writable;

8. `send` the response bytes back to the client and close the socket.

Each of these stages could be a state machine which runs in parallel with all

the other stages. Structuring services in this pipeline fashion was

[advocated](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3eo49nVxcA&t=1949s) by the late Jim

Gray and more recently Martin Thompson et al have

[been](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qDhTjE0XmkE) giving

[talks](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KvFapRkR9I) using a similar approach.

If a stage is slow, we can shard (or partition, using Jim's terminology) it by

dedicating another CPU/core to that stage and have even numbered requests to one

CPU/core while odd numbered requests go to the other. That way we effectively

double the throughput, without breaking determinism.

Let me just leave you with one final image. I like to think of state machines on

top of pipelines as a limited form of actors or Erlang processes (`gen_server`s

more precisely) that cannot send messages to which other process they like

(graph-like structure), but rather only downstream (DAG-like structure)[^3].

## Implementation

I hope that I've managed to convey what I'd like to do, why and where my

inspiration is coming from.

Next I'd like to make things more concrete with some code. But first I'd like to

apologies for my choice of using Haskell. I know it's a language that not that

many people are comfortable with, but its advanced type system (GADTs in

particular) helps me express things more cleanly. If anything isn't clear, feel

free to ask, I'm happy to try to explain things in simpler terms. Also if anyone

knows how to express this without GADTs, while retaining type safety, then

please let me know. The code doesn't add anything new to our previous

discussion, merely validates that at least some of it can be implemented, so

even if you can't follow everything you won't be missing out on anything

important.

A few notes on the implementation:

* To keep things simple we'll only implement linear pipelines. Each stage of the

pipeline runs in parallel with all other stages, thus giving us pipelining

parallelism à la assembly lines;

* The transformation at each stage is done via a state machine. The syntax of

state machines needs to be easily serialisable, so that we can send upgrades

over the wire;

* The remote end will need to deserialise and typecheck the receiving code in

order to assure that it's compatible with the already deployed code.

In the rest of this section we'll try to fleshing out details of the above.

### State machines

Typed state machines are represented using a datatype parametrised by the state,

`s`, and indexed by its input type, `a`, and output type `b`[^4]. For example

the `Id`entity state machine has the same input and output type, while if we

want to `Compose` to state machines then output type of the first needs to be

the same as the input type of the second, and so on.

```haskell

data T s a b where

-- Identity and composition.

Id :: T s a a

Compose :: T s b c -> T s a b -> T s a c

-- Introducing and incrementing integers.

Int :: Int -> T s () Int

Incr :: T s Int Int

-- Mapping over sum types.

Case :: T s a c -> T s b d -> T s (Either a b) (Either c d)

-- Read and update the state.

Get :: T s () s

Put :: T s s ()

-- Converting values from and to strings.

Read :: Read a => T s String a

Show :: Show a => T s a String

-- Forward composition.

(>>>) :: T s a b -> T s b c -> T s a c

f >>> g = g `Compose` f

```

### Example

To keep things concrete let's reimplement the counter example from above.

```haskell

type InputV1 = Either () ()

type OutputV1 = Either Int ()

pattern ReadCountV1 :: InputV1

pattern ReadCountV1 = Left ()

pattern IncrCountV1 :: InputV1

pattern IncrCountV1 = Right ()

counterV1 :: T Int String String

counterV1 = Read >>> counterV1' >>> Show

where

counterV1' :: T Int InputV1 OutputV1

counterV1' = Get `Case` (Get >>> Incr >>> Put)

```

Notice how the two operations' inputs and outputs are represented with an

`Either` over which the `Case` operates.

### Semantics

We can interpret our typed state machines in terms of the `State` monad as

follows.

```haskell

runT :: T s a b -> a -> s -> (b, s)

runT f x s = runState (eval f x) s

eval :: T s a b -> a -> State s b

eval Id = return

eval (Compose g f) = eval g <=< eval f

eval (Int i) = return . const i

eval Incr = return . (+ 1)

eval (Case f g) = either (fmap Left . eval f) (fmap Right . eval g)

eval Get = const get

eval Put = put

eval Read = return . read

eval Show = return . show

```

Using the above interpreter we can run our example from before.

```haskell

> runT counterV1 (show ReadCountV1) 0

("Left 0",0)

> runT counterV1 (show IncrCountV1) 0

("Right ()",1)

> runT counterV1 (show ReadCountV1) 1

("Left 1",1)

```

These runs only step the counter by one input at the time, things get more

interesting when state machines get streams of inputs via pipelines.

### Pipelines

Pipelines are represented by a type similar to that for typed state machines,

it's also indexed by the input and output types.

We can picture a pipeline as a conveyor belt with state machines operating on

the items passing through.

```haskell

data P a b where

IdP :: P a a

(:>>>) :: Typeable b => P a b -> P b c -> P a c

SM :: Typeable s => Name -> s -> T s a b -> P a b

type Name = String

```

Notice how the state type of the state machines is existentially quantified,

meaning each state machine can have its own state.

### Deployment

Pipelines can be deployed. Each state machine will be spawned on its own thread,

meaning that all state machines run in parallel, and they will be connected via

queues.

Given a pipeline `P a b` and an input `Queue (Msg a)` we get an output `Queue

(Msg b)`:

```haskell

deploy :: forall a b. (Typeable a, Typeable b)

=> P a b -> Queue (Msg a) -> IO (Queue (Msg b))

```

where `Msg` is defined as follows.

```haskell

data Msg a

= Item (Maybe Socket) a

| Upgrade (Maybe Socket) Name UpgradeData_

...

```

Think of `Msg a` as small wrapper around `a` which might contain a client socket

(so that we know where to send the reply), or an upgrade. Upgrades are targeting

a specific state machine in our pipeline, that's what the `Name` parameter is

for, and they also carry an untyped `UpgradeData_` payload which will come back

to shortly.

Given the above we can define deployment of pipelines as follows (I'll explain

each case below the code).

```haskell

deploy IdP q = return q

deploy (f :>>> g) q = deploy g =<< deploy f q

deploy (SM name s0 f0) q = do

q' <- newQueue

let go :: Typeable s => s -> T s a b -> IO ()

go s f = do

m <- readQueue q

case m of

Item msock i -> do

let (o, s') = runT f i s

writeQueue q' (Item msock o)

go s' f

Upgrade msock name' ud

| name /= name' -> do

writeQueue q' (Upgrade msock name' ud)

go s f

| otherwise ->

case typeCheckUpgrade f ud of

Just (UpgradeData (f' :: T t' a b) (g :: T () s t')) -> do

let (t', ()) = runT g s ()

case cast t' of

Just s' -> go s' f'

Nothing -> go s f

Nothing -> go s f

...

_pid <- forkIO (go s0 f0)

return q'

```

The identity pipeline simply returns the input queue. We deploy compositions of

pipelines by deploying the components and connecting the queues. Deploying state

machines is the interesting part.

When we deploy state machines, we first create a new queue which will hold the

outputs, we then fork a new thread which reads from the input queue and writes

to this new output queue, and finally we return the output queue. When reading

from the input queue there're two cases:

1. We can either get a regular `Item` in which case we step our state machine

using the `runT` function to obtain an output and a new state, we write the

output to the output queue and continue processing with the new state;

2. Or, if the `Msg` is an `Upgrade` we first check if the upgrade is targeting

this state machine by checking if the names match, if not we simply pass it

further downstream. If the names to match then we try to typecheck the

untyped `UpgradeData_`. If the typechecking succeeds, we'll get a new state

machine and a state migration function, which allows us to migrate the

current state and continue processing with the new state machine.

Next let's have a look at how upgrades are represented and typechecked.

### Upgrades

Upgrades are sent over the wire in a serialised format and deserialised at the

other end, so they need to be plain first-order data.

This means we can't merely send over our typed state machine type `t :: T s a

b`, or rather the receiver will have to reconstruct the type information. If

this sounds strange, the perhaps easiest way to convince yourself is to imagine

you receive `show t` and now you want to reconstruct `t`. When you call `read

(show t)` you need to annotate it with what type to read into, and that's the

problem: at this point you don't have the type annotation `T s a b`.

So the plan around this is to introduce a plain first-order datatype for

upgrades, which can easily be serialised and deserialised, and then use

*typechecking* to reconstruct the type information.

```haskell

data UpgradeData_ = UpgradeData_

{ oldState :: Ty_

, newState :: Ty_

, newInput :: Ty_

, newOutput :: Ty_

, newStateMachine :: U

, stateMigration :: U

}

deriving (Show, Read)

```

We can to typecheck the above untyped upgrade into the following typed version.

```haskell

data UpgradeData s a b = forall s'. Typeable s' =>

UpgradeData (T s' a b) (T () s s')

```

The way typechecking for upgrades work is basically the user needs to provide

the untyped types of the state, input and output types of the new state machine

as well as the state migration function, from the untyped types we can infer the

typed types which we then typecheck the new state machine and migration function

against.

```haskell

typeCheckUpgrade :: forall s a b. (Typeable s, Typeable a, Typeable b)

=> T s a b -> UpgradeData_ -> Maybe (UpgradeData s a b)

typeCheckUpgrade _f (UpgradeData_ t_ t'_ a'_ b'_ f_ g_) =

case (inferTy t_, inferTy t'_, inferTy a'_, inferTy b'_) of

(ETy (t :: Ty t), ETy (t' :: Ty t'), ETy (a' :: Ty a'), ETy (b' :: Ty b')) -> do

Refl <- decT @a @a'

Refl <- decT @b @b'

Refl <- decT @s @t

f <- typeCheck f_ t' a' b'

g <- typeCheck g_ TUnit t t'

return (UpgradeData f g)

```

Where untyped types are defined as follows:

```haskell

data Ty_

= UTUnit

| UTInt

| UTBool

| UTString

| UTPair Ty_ Ty_

| UTEither Ty_ Ty_

```

and typed types as follows:

```haskell

data Ty a where

TUnit :: Ty ()

TInt :: Ty Int

TBool :: Ty Bool

TString :: Ty String

TPair :: Ty a -> Ty b -> Ty (a, b)

TEither :: Ty a -> Ty b -> Ty (Either a b)

...

```

and the way we infer typed types from the untyped ones is done as follows:

```haskell

data ETy where

ETy :: Typeable a => Ty a -> ETy

inferTy :: Ty_ -> ETy

inferTy UTUnit = ETy TUnit

inferTy UTInt = ETy TInt

inferTy UTBool = ETy TBool

inferTy UTString = ETy TString

inferTy (UTPair ua ub) = case (inferTy ua, inferTy ub) of

(ETy a, ETy b) -> ETy (TPair a b)

inferTy (UTEither ua ub) = case (inferTy ua, inferTy ub) of

(ETy a, ETy b) -> ETy (TEither a b)

```

Now the only piece missing is untyped state machines and how to typecheck those

into typed ones.

```haskell

typeCheck :: U -> Ty s -> Ty a -> Ty b -> Maybe (T s a b)

data U

= IdU

| ComposeU U U

| IntU Int

| CaseU U U

| IncrU

| GetU

| PutU

| ReadU Ty_

| ShowU Ty_

```

I'll spare you from the

[details](https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2/blob/main/src/TypeCheck/StateMachine.hs),

but the main ingredient is to use the `Data.Typeable` instances to check if the

types match up, similarly to how it was done above in `typeCheckUpgrade`.

### Sources and sinks

Almost there. When we deploy a pipeline `P a b` we need to provide a `Queue (Msg

a)` and get a `Queue (Msg b)`, what are we supposed to do with those queues? We

could manually feed them with items, but for convenience it's nice to have some

basic reusable adapters that we can connect these "garden hoses" to.

We call something that provides an input queue a `Source` and something that

consumes an output queue a `Sink`. Useful sources and sinks include

stdin/stdout, files, and TCP streams.

We can then implement a run function with the following type:

```haskell

run :: (Typeable a, Typeable b)

=> Source a -> Codec (Msg a) (Msg b) -> P a b -> Sink b r -> IO r

```

Where `Codec a b` contains a deserialiser from `ByteString` to `Maybe a` and a

serialiser from `b` to `ByteString`. We need this because our sources and sinks

produce and consume `ByteString`s.

### Remote upgrades

Putting it all together we can now create a TCP server for our counter:

```haskell

run (FromTCP "127.0.0.1" 3000) readShowCodec (SM "counter" 0 counterV1) ToTCP

```

If we run the above in a REPL, then from another terminal we can interact with

the server as follows.

```bash

# Get the current state of the counter.

$ echo 'Item "Left ()"' | nc 127.0.0.1 3000

Item "Left 0"

# Increment the counter.

$ echo 'Item "Right ()"' | nc 127.0.0.1 3000

Item "Right ()"

# Read the counter again.

$ echo 'Item "Left ()"' | nc 127.0.0.1 3000

Item "Left 1"

```

In order to make life a bit easier for ourselves, we can implement a simple TCP

client in Haskell and use from another REPL to achieve the same result.

```haskell

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV1))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show IncrCountV1))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show IncrCountV1))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV1))

```

```

Item "Left 0" -- The initial value of the counter is 0.

Item "Right ()" -- Two increments.

Item "Right ()"

Item "Left 2" -- The value is now 2

```

At this point, let's imagine we want to add a reset feature to our counter.

Reset takes no argument and returns nothing, so we use the unit type in both the

input and output types.

```haskell

type InputV2 = Either () InputV1

type OutputV2 = Either () OutputV1

pattern ResetCountV2 :: InputV2

pattern ResetCountV2 = Left ()

pattern ReadCountV2 :: InputV2

pattern ReadCountV2 = Right ReadCountV1

pattern IncrCountV2 :: InputV2

pattern IncrCountV2 = Right IncrCountV1

```

The state machine looks the same, except for the first `Case` where we update the

state to be `0`, thus resetting the counter.

```haskell

counterV2 :: T Int String String

counterV2 = Read >>> counterV2' >>> Show

where

counterV2' :: T Int InputV2 OutputV2

counterV2' =

(Int 0 >>> Put) `Case`

Get `Case`

(Get >>> Incr >>> Put)

```

Back in our REPL we can now do the upgrade, by sending over a type `erase`d

version of `counterV2`.

```haskell

let msg :: Msg ()

msg = Upgrade Nothing "counter"

(UpgradeData_ UTInt UTInt UTString UTString (erase counterV2) (erase Id))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 msg

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV2))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ResetCountV2))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV2))

```

Which yields the following annotated output.

```

UpgradeSucceeded "counter"

Item "Right (Left 2)" -- The counter's state is preserved by the upgrade.

Item "Left ()" -- Reset the counter.

Item "Right (Left 0)" -- The value is back to 0.

```

As a final example of an upgrade, let's do a more interesting state migration.

Let's say we want to add a boolean to the state which determines if `IncrCount`

should add by `1` or `-1` (i.e. decrement). This boolean can be toggled by the

user using a new operation, while the signatures of the other operations stay

the same as before.

```haskell

type InputV3 = Either () InputV2

type OutputV3 = Either () OutputV2

pattern ToggleCountV3 :: InputV3

pattern ToggleCountV3 = Left ()

pattern ReadCountV3, IncrCountV3, ToggleCountV3 :: InputV3

```

In order to implement the toggle operation we need to extend the syntax of our

state machines to be able to deal with booleans and products (the details can be

found

[here](https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2/blob/main/src/Interpreter.hs)).

```haskell

counterV3 :: T (Int, Bool) String String

counterV3 = Read >>> counterV3' >>> Show

where

counterV3' :: T (Int, Bool) InputV3 OutputV3

counterV3' =

-- Toggle negates the boolean in the state (the second component).

(Get >>> Second Not >>> Put) `Case`

-- Reset resets the counter and the boolean back to false (i.e. incrementing).

(Int 0 :&&& Bool False >>> Put) `Case`

-- Reading the counter picks out the first component from the state.

(Get >>> Fst) `Case`

-- Incrementing or decrementing, depending on the boolean in the state.

(Get >>> If Decr Incr >>> (Id :&&& (Consume >>> Get >>> Snd)) >>> Put)

```

We can then upgrade to our new version of the counter as follows.

```haskell

let msg2 :: Msg ()

msg2 = Upgrade Nothing "counter"

(UpgradeData_ UTInt (UTPair UTInt UTBool) UTString UTString

(erase counterV3) (erase (Id :&&& Bool False)))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 msg2

```

Notice how the state is migrated using `Id :&&& Bool False`, i.e. create a pair

where the first component is the old value of the state (this is the current

count) and the second component is `False` (this is whether we are decrementing).

Here's a final example of how we can use the new counter.

```haskell

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show IncrCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show IncrCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ToggleCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show IncrCountV3))

nc "127.0.0.1" 3000 (Item Nothing (show ReadCountV3))

```

The above yields the following output.

```

UpgradeSucceeded "counter"

Item "Right (Right (Left 0))" -- The counter is 0.

Item "Right (Right (Right ()))" -- Two increments.

Item "Right (Right (Right ()))"

Item "Right (Right (Left 2))" -- The counter is 2.

Item "Left ()" -- Toggle to decrementing.

Item "Right (Right (Right ()))" -- Decrement.

Item "Right (Right (Left 1))" -- The value is 1.

```

## Discussion and future work

If we look back at the list, from the introduction, of properties that we wanted

from our upgrades, then I hope that I've managed to provide a glimpse of a

possible way of achieving zero-downtime upgrades with type-safe state migrations

that are atomic.

Downgrades can be thought of as an upgrade to an earlier version, although it

could be interesting to experiment with requiring an inverse function to the

state migration as part of an upgrade. That way the system itself could

downgrade in case there's more than N errors within some time period, or

something like that.

I didn't talk about backwards and forwards compatibility. We could probably use

an [interface description

language](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interface_description_language), such as

Avro or Protobuf, but it could also be interesting see if we could add input and

output migrations as part of upgrades (in addition to state migrations).

Especially in conjunction with being able to derive them generically and

[automatically](https://www.manuelbaerenz.de/essence-of-live-coding/EssenceOfLiveCoding.pdf)

from the schema change.

There's also a bunch of other

[things](https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2/blob/main/TODO.md)

that I thought of while working on this, which I don't have any good answers for

yet. If you feel that I'm missing something, or if you know some answers or if

any of these problems sound interesting to work on, please do feel free to get

in [touch](https://stevana.github.io/about.html)!

Let me close by trying to tie it back to Barbara Liskov's remark about the need

for more complete programming languages. In a world where software systems are

expected to evolve over time, wouldn't it be neat if programming languages

provided some notion of upgrade and could typecheck our code *across versions*,

as opposed to merely typechecking a version of the code in isolation from the

next?

[^1]: State machines might seem like low-level clumsy way of programming, but

Yuri Gurevich has

[shown](https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/103-evolving-algebras-1993-lipari-guide/)

that abstract state machines (state machines where state can be any

first-order structure) can avoid the Turing tarpit and capture any algorithm

at any level of abstraction. This result is a generalisation of the

Church-Turing thesis from computable functions on natural numbers to

arbitrary sequential algorithms.

In case you're not convinced by this theoretical argument, then here are a

couple of practical examples of state machine use from industry.

In Joe Armstrong's PhD

[thesis](http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A9492&dswid=-4551)

(2003), Joe gives an example of a big Ericsson telecommunications system

built in Erlang/OTP using a handful of library constructs (behaviours). The

most commonly used of these building blocks is `gen_server`, which is a

state machine. I've written a high-level summary of the ideas over

[here](https://stevana.github.io/erlangs_not_about_lightweight_processes_and_message_passing.html),

although I recommend reading his thesis and forming your own conclusions.

Leslie Lamport is another proponent of state machines. His TLA+ is basically

a language for describing state machines. See his article [*Computation and

State

Machines*](https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/computation-state-machines/)

(2008) for an introduction. Fault tolerance in distributed systems is often

realised by means of replicated state machines, which Leslie helped develop

back in the 80s.

Jean-Raymond Abrial's B-method (a successor to Z notation) is also centered

around state machines and has been used to verify the automatic Paris Métro

lines 14 and 1 and the Ariane 5 rocket.

[^2]: Many years ago I had the pleasure to study interaction structures (aka

index containers aka polynomial functors). One of many possible way to view

these structures is as if they are state machines. One can construct a

category with the objects being interaction structures and then think about

what the morphisms must look like in order to satisfy the necessary

categorical laws.

I don't know much about category theory myself, but I remember that the

morphisms in the resulting category have two components and they look

exactly like those that we needed to be able to support backwards

compatibility.

There's also a strong [connection](https://arxiv.org/abs/0905.4063v1)

between this category and stepwise refinement or refinement calculus, which

at least intuitively has some connection with upgrades.

I suppose that there are more useful ideas to steal from there.

[^3]: This restriction makes it easier to make everything deterministic, which

in turn makes it easier to (simulation) test. I touch upon this in an

earlier

[post](https://stevana.github.io/erlangs_not_about_lightweight_processes_and_message_passing.html)

towards the end. I hope to expand upon this in a separate post at some point

in the future.

It also make it possible for the implementation to be more efficient. For

example, if we want to have a pipeline that takes the output of one state

machine and broadcasts it to two other state machines (on the same computer)

then in Erlang the output would be copied to the two state machines

downstream, whereas with pipelines we can do it [without

copying](https://stevana.github.io/parallel_stream_processing_with_zero-copy_fan-out_and_sharding.html).

[^4]: People familiar with Haskell's ecosystem might recognise that this is an

instance of

[`Category`](https://hackage.haskell.org/package/base-4.19.1.0/docs/Control-Category.html)

and partially an instance of

[`Cocartesian`](https://github.com/stevana/hot-swapping-state-machines2/blob/main/src/Classes.hs#L13),

plus some extras. In a "real" implementation we would want this datatype to

be an instance of `Cocartesian` instance as well as `Cartesian`.