https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor

Experiment in creating parallel pipelines using the Disruptor.

https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor

dataflow disruptor parallel-programming pipelining

Last synced: about 1 month ago

JSON representation

Experiment in creating parallel pipelines using the Disruptor.

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor

- Owner: stevana

- License: bsd-2-clause

- Created: 2023-08-30T10:54:41.000Z (about 2 years ago)

- Default Branch: main

- Last Pushed: 2024-01-31T07:33:12.000Z (over 1 year ago)

- Last Synced: 2025-08-02T20:57:06.605Z (2 months ago)

- Topics: dataflow, disruptor, parallel-programming, pipelining

- Language: Haskell

- Homepage:

- Size: 155 KB

- Stars: 6

- Watchers: 3

- Forks: 0

- Open Issues: 0

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- Changelog: CHANGELOG.md

- License: LICENSE

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

# Parallel stream processing with zero-copy fan-out and sharding

In a previous [post](https://stevana.github.io/pipelined_state_machines.html) I

explored how we can make better use of our parallel hardware by means of

pipelining.

In a nutshell the idea of pipelining is to break up the problem in stages and

have one (or more) thread(s) per stage and then connect the stages with queues.

For example, imagine a service where we read some request from a socket, parse

it, validate, update our state and construct a response, serialise the response

and send it back over the socket. These are six distinct stages and we could

create a pipeline with six CPUs/cores each working on a their own stage and

feeding the output to the queue of the next stage. If one stage is slow we can

shard the input, e.g. even requests to go to one worker and odd requests go to

another thereby nearly doubling the throughput for that stage.

One of the concluding remarks to the previous post is that we can gain even more

performance by using a better implementation of queues, e.g. the [LMAX

Disruptor](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disruptor_(software)).

The Disruptor is a low-latency high-throughput queue implementation with support

for multi-cast (many consumers can in parallel process the same event), batching

(both on producer and consumer side), back-pressure, sharding (for scalability)

and dependencies between consumers.

In this post we'll recall the problem of using "normal" queues, discuss how

Disruptor helps solve this problem and have a look at how we can we provide a

declarative high-level language for expressing pipelines backed by Disruptors

where all low-level details are hidden away from the user of the library. We'll

also have a look at how we can monitor and visualise such pipelines for

debugging and performance troubleshooting purposes.

## Motivation and inspiration

Before we dive into *how* we can achieve this, let's start with the question of

*why* I'd like to do it.

I believe the way we write programs for multiprocessor networks, i.e. multiple

connected computers each with multiple CPUs/cores, can be improved upon. Instead

of focusing on the pitfalls of the current mainstream approaches to these

problems, let's have a look at what to me seems like the most promising way

forward.

Jim Gray gave a great explanation of dataflow programming in this Turing Award

Recipient [interview](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3eo49nVxcA&t=1949s). He

uses props to make his point, which makes it a bit difficult to summaries in

text here. I highly recommend watching the video clip, the relevant part is only

three minutes long.

The key point is exactly that of pipelining. Each stage is running on a

CPU/core, this program is completely sequential, but by connecting several

stages we create a parallel pipeline. Further parallelism (what Jim calls

partitioned parallelism) can be gained by partitioning the inputs, by say odd

and even sequence number, and feeding one half of the inputs to one copy of the

pipeline and the other half to another copy, thereby almost doubling the

throughput. Jim calls this a "natural" way to achieve parallelism.

While I'm not sure if "natural" is the best word, I do agree that it's a nice

way to make good use of CPUs/cores on a single computer without introducing

non-determinism. Pipelining is also effectively used to achieve parallelism in

manufacturing and hardware, perhaps that's why Jim calls it "natural"?

Things get a bit more tricky if we want to involve more computers. Part of the

reason, I believe, is that we run into the problem highlighted by Barbara Liskov

at the very end of her Turing award

[lecture](https://youtu.be/qAKrMdUycb8?t=3058) (2009):

> "There's a funny disconnect in how we write distributed programs. You

> write your individual modules, but then when you want to connect

> them together you're out of the programming language and into this

> other world. Maybe we need languages that are a little bit more

> complete now, so that we can write the whole thing in the language."

Ideally we'd like our pipelines to seamlessly span over multiple computers. In

fact it should be possible to deploy same pipeline to different configurations

of processors without changing the pipeline code (nor having to add any

networking related code).

A pipeline that is redeployed with additional CPUs or computers might or might

not scale, it depends on whether it makes sense to partition the input of a

stage further or if perhaps the introduction of an additional computer merely

adds more overhead. How exactly the pipeline is best spread over the available

computers and CPUs/cores will require some combination of domain knowledge,

measurement and judgment. Depending on how quick we can make redeploying of

pipelines, it might be possible to autoscale them using a program that monitors

the queue lengths.

Also related to redeploying, but even more important than autoscaling, are

upgrades of pipelines. That's both upgrading the code running at the individual

stages, as well as how the stages are connected to each other, i.e. the

pipeline itself.

Martin Thompson has given many

[talks](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KvFapRkR9I) which echo the general

ideas of Jim and Barbara. If you prefer reading then you can also have a look at

the [reactive manifesto](https://www.reactivemanifesto.org/) which he cowrote.

Martin is also one of the people behind the Disruptor, which we will come back

to soon, and he also [said](https://youtu.be/OqsAGFExFgQ?t=2532) the following:

> "If there's one thing I'd say to the Erlang folks, it's you got the stuff right

> from a high-level, but you need to invest in your messaging infrastructure so

> it's super fast, super efficient and obeys all the right properties to let this

> stuff work really well."

This quote together with Joe Armstrong's

[anecdote](https://youtu.be/bo5WL5IQAd0?t=2494) of an unmodified Erlang program

*only* running 33 times faster on a 64 core machine, rather than 64 times faster

as per the Ericsson higher-up's expectations, inspired me to think about how one

can improve upon the already excellent work that Erlang is doing in this space.

Longer term, I like to think of pipelines spanning computers as a building block

for what Barbara [calls](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8M0wTX6EOVI) a

"substrate for distributed systems". Unlike Barbara I don't think this substrate

should be based on shared memory, but overall I agree with her goal of making it

easier to program distributed systems by providing generic building blocks.

## Prior work

Working with streams of data is common. The reason for this is that it's a nice

abstraction when dealing with data that cannot fit in memory. The alternative is

to manually load chunks of data one wants to process into memory, load the next

chunk etc, when we processes streams this is hidden away from us.

Parallelism is a related problem, in that when one has big volumes of data it's

also common to care about performance and how we can utilise multiple

processors.

Since dealing with limited memory and multiprocessors is a problem that as

bothered programmers and computer scientists for a long time, at least since the

1960s, there's a lot of work that has been done in this area. I'm at best

familiar with a small fraction of this work, so please bear with me but also do

let me know if I missed any important development.

In 1963 Melvin Conway proposed

[coroutines](https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/366663.366704), which allows the

user to conveniently process very large, or even infinite, lists of items

without first loading the list into memory, i.e. streaming.

Shortly after, in 1965, Peter Landin introduced

[streams](https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/363744.363749) as a functional analogue

of Melvin's imperative coroutines.

A more radical departure from Von Neumann style sequential programming can be

seen in the work on [dataflow

programming](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dataflow_programming) in general and

especially in Paul Morrison's [flow-based

programming](https://jpaulm.github.io/fbp/index.html) (late 1960s). Paul uses

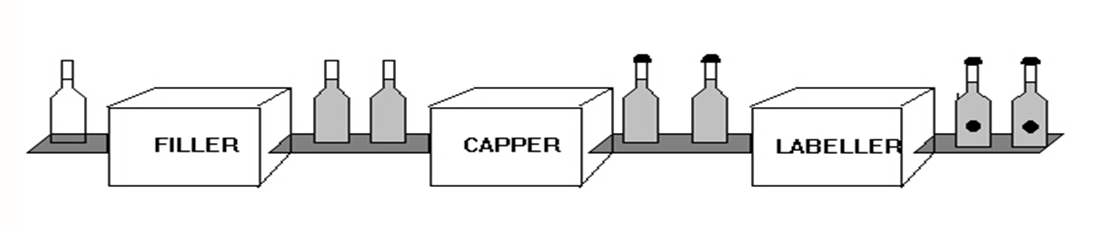

the following picture to illustrate the similarity between flow-based

programming and an assembly line in manufacturing:

Each stage is its own process running in parallel with the other stages. In

flow-based programming stages are computation and the conveyor belts are queues.

This gives us implicit parallelism and determinate outcome.

Doug McIlroy, who was aware of some of the dataflow work[^1], wrote a

[memo](http://doc.cat-v.org/unix/pipes/) in 1964 about the idea of pipes,

although it took until 1973 for them to get implemented in Unix by Ken Thompson.

Unix pipes have a strong feel of flow-based programming, although all data is of

type string. A pipeline of commands will start a process per command, so there's

implicit parallelism as well (assuming the operative system schedules different

processes on different CPUs/cores). Fanning out can be done with `tee` and

process substitution, e.g. `echo foo | tee >(cat) >(cat) | cat`, and more

complicated non-linear flows can be achieved with `mkfifo`.

With the release of GNU [`parallel`](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_parallel)

in 2010 more explicit control over parallelism was introduced as well as the

ability to run jobs on remote computers.

Around the same time many (functional) programming languages started getting

streaming libraries. Haskell's

[conduit](https://hackage.haskell.org/package/conduit) library had its first

release in 2011 and Haskell's [pipes](https://hackage.haskell.org/package/pipes)

library came shortly after (2012). Java version 8, which has streams, was

released in 2014. Both [Clojure](https://clojure.org/reference/transducers) and

[Scala](https://doc.akka.io/docs/akka/current/stream/index.html), which also use

the JVM, got streams that same year (2014).

Among the more imperative programming languages, JavaScript and Python both have

generators (a simple form of coroutines) since around 2006. Go has "goroutines",

a clear nod to coroutines, since its first version (2009). Coroutines are also

part of the C++20 standard.

Almost all of the above mentioned streaming libraries are intended to be run on

a single computer. Often they even run in a single thread, i.e. not exploiting

parallelism at all. Sometimes concurrent/async constructs are available which

create a pool of worker threads that process the items concurrently, but they

often break determinism (i.e. rerunning the same computation will yield

different results, because the workers do not preserve the order of the inputs).

If the data volumes are too big for a single computer then there's a different

set of streaming tools, such as Apache Hadoop (2006), Apache Spark (2009),

Apache Kafka (2011), Apache Storm (2011), and Apache Flink (2011). While the

Apache tools can often be deployed locally for testing purposes, they are

intended for distributed computations and are therefore perhaps a bit more

cumbersome to deploy and use than the streaming libraries we mentioned earlier.

Initially it might not seem like a big deal that streaming libraries don't

"scale up" or distributed over multiple computers, and that streaming tools like

the Apache ones don't gracefully "scale down" to a single computer. Just pick

the right tool for the right job, right? Well, it turns out that

[40-80%](https://youtu.be/XPlXNUXmcgE?t=2783) of jobs submitted to MapReduce

systems (such as Apache Hadoop) would run faster if they were ran on a single

computer instead of a distributed cluster of computers, so picking the right

tool is perhaps not as easy as it first seems.

There are two exceptions, that I know of, of streaming libraries that also work

in a distributed setting. Scala's Akka/Pekko

[streams](https://doc.akka.io/docs/akka/current/stream/stream-refs.html) (2014)

when combined with Akka/Pekko

[clusters](https://github.com/apache/incubator-pekko-management) and

[Aeron](https://aeron.io/) (2014). Aeron is the spiritual successor of the

Disruptor also written by Martin Thompson et al. The Disruptor's main use case

was as part of the LMAX exchange. From what I understand exchanges close in the

evening (or at least did back then in the case of LMAX), which allows for

updates etc. These requirements changed for Aeron where 24/7 operation was

necessary and so distributed stream processing is necessary where upgrades can

happen without processing stopping (or even slowing down).

Finally, I'd also like to mention functional reactive programming, or FRP,

(1997). I like to think of it as a neat way of expressing stream processing

networks. Disruptor's

["wizard"](https://github.com/LMAX-Exchange/disruptor/wiki/Disruptor-Wizard) DSL

and Akka's [graph

DSL](https://doc.akka.io/docs/akka/current/stream/stream-graphs.html) try to add

a high-level syntax for expressing networks, but they both have a rather

imperative rather than declarative feel. It's however not clear (to me) how

effectively implement, parallelise[^2], or distribute FRP. Some interesting work

has been done with hot code swapping in the FRP

[setting](https://github.com/turion/essence-of-live-coding), which is

potentially useful for a telling a good upgrade story.

To summarise, while there are many streaming libraries there seem to be few (at

least that I know of) that tick all of the following boxes:

1. Parallel processing:

* in a determinate way;

* fanning out and sharding without copying data (when run on a single

computer).

2. Potentially distributed over multiple computers for fault tolerance and

upgrades, without the need to change the code of the pipeline;

3. Observable, to ease debugging and performance analysis;

4. Declarative high-level way of expressing stream processing networks (i.e.

the pipeline);

5. Good deploy, upgrade, rescale story for stateful systems;

6. Elastic, i.e. ability to rescale automatically to meet the load.

I think we need all of the above in order to build Barbara's "substrate for

distributed systems". We'll not get all the way there in this post, but at least

this should give you a sense of the direction I'd like to go.

## Plan

The rest of this post is organised as follows.

First we'll have a look at how to model pipelines as a transformation of lists.

The purpose of this is to give us an easy to understand sequential specification

of what we would like our pipelines to do.

We'll then give our first parallel implementation of pipelines using "normal"

queues. The main point here is to recap of the problem with copying data that

arises from using "normal" queues, but we'll also sketch how one can test the

parallel implementation using the model.

After that we'll have a look at the Disruptor API, sketch its single producer

implementation and discuss how it helps solve the problems we identified in the

previous section.

Finally we'll have enough background to be able to sketch the Disruptor

implementation of pipelines. We'll also discuss how monitoring/observability can

be added.

## List transformer model

Let's first introduce the type for our pipelines. We index our pipeline datatype

by two types, in order to be able to precisely specify its input and output

types. For example, the `Id`entity pipeline has the same input as output type,

while pipeline composition (`:>>>`) expects its first argument to be a pipeline

from `a` to `b`, and the second argument a pipeline from `b` to `c` in order for

the resulting composed pipeline to be from `a` to `c` (similar to functional

composition).

```haskell

data P :: Type -> Type -> Type where

Id :: P a a

(:>>>) :: P a b -> P b c -> P a c

Map :: (a -> b) -> P a b

(:***) :: P a c -> P b d -> P (a, b) (c, d)

(:&&&) :: P a b -> P a c -> P a (b, c)

(:+++) :: P a c -> P b d -> P (Either a b) (Either c d)

(:|||) :: P a c -> P b c -> P (Either a b) c

Shard :: P a b -> P a b

```

Here's a pipeline that takes a stream of integers as input and outputs a stream

of pairs where the first component is the input integer and the second component

is a boolean indicating if the first component was an even integer or not.

```haskell

examplePipeline :: P Int (Int, Bool)

examplePipeline = Id :&&& Map even

```

So far our pipelines are merely data which describes what we'd like to do. In

order to actually perform a stream transformation we'd need to give semantics to

our pipeline datatype[^3].

The simplest semantics we can give our pipelines is that in terms of list

transformations.

```haskell

model :: P a b -> [a] -> [b]

model Id xs = xs

model (f :>>> g) xs = model g (model f xs)

model (Map f) xs = map f xs

model (f :*** g) xys =

let

(xs, ys) = unzip xys

in

zip (model f xs) (model g ys)

model (f :&&& g) xs = zip (model f xs) (model g xs)

model (f :+++ g) es =

let

(xs, ys) = partitionEithers es

in

-- Note that we pass in the input list, in order to perserve the order.

merge es (model f xs) (model g ys)

where

merge [] [] [] = []

merge (Left _ : es) (l : ls) rs = Left l : merge es ls rs

merge (Right _ : es) ls (r : rs) = Right r : merge es ls rs

model (f :||| g) es =

let

(xs, ys) = partitionEithers es

in

merge es (model f xs) (model g ys)

where

merge [] [] [] = []

merge (Left _ : es) (l : ls) rs = l : merge es ls rs

merge (Right _ : es) ls (r : rs) = r : merge es ls rs

model (Shard f) xs = model f xs

```

Note that this semantics is completely sequential and preserves the order of the

inputs (determinism). Also note that since we don't have parallelism yet,

`Shard`ing doesn't do anything. We'll introduce parallelism without breaking

determinism in the next section.

We can now run our example pipeline in the REPL:

```

> model examplePipeline [1,2,3,4,5]

[(1,False),(2,True),(3,False),(4,True),(5,False)]

```

## Queue pipeline deployment

In the previous section we saw how to deploy pipelines in a purely sequential

way in order to process lists. The purpose of this is merely to give ourselves

an intuition of what pipelines should do as well as an executable model which we

can test our intuition against.

Next we shall have a look at our first parallel deployment. The idea here is to

show how we can involve multiple threads in the stream processing, without

making the output non-deterministic (same input should always give the same

output).

We can achieve this as follows:

```haskell

deploy :: P a b -> TQueue a -> IO (TQueue b)

deploy Id xs = return xs

deploy (f :>>> g) xs = deploy g =<< deploy f xs

deploy (Map f) xs = deploy (MapM (return . f)) xs

deploy (MapM f) xs = do

-- (Where `MapM :: (a -> IO b) -> P a b` is the monadic generalisation of

-- `Map` from the list model that we saw earlier.)

ys <- newTQueueIO

forkIO $ forever $ do

x <- atomically (readTQueue xs)

y <- f x

atomically (writeTQueue ys y)

return ys

deploy (f :&&& g) xs = do

xs1 <- newTQueueIO

xs2 <- newTQueueIO

forkIO $ forever $ do

x <- atomically (readTQueue xs)

atomically $ do

writeTQueue xs1 x

writeTQueue xs2 x

ys <- deploy f xs1

zs <- deploy g xs2

yzs <- newTQueueIO

forkIO $ forever $ do

y <- atomically (readTQueue ys)

z <- atomically (readTQueue zs)

atomically (writeTQueue yzs (y, z))

return yzs

```

(I've omitted the cases for `:|||` and `:+++` to not take up too much space.

We'll come back and handle `Shard` separately later.)

```haskell

example' :: [Int] -> IO [(Int, Bool)]

example' xs0 = do

xs <- newTQueueIO

mapM_ (atomically . writeTQueue xs) xs0

ys <- deploy (Id :&&& Map even) xs

replicateM (length xs0) (atomically (readTQueue ys))

```

Running

[this](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/QueueDeployment.hs)

in our REPL, gives the same result as in the model:

```

> example' [1,2,3,4,5]

[(1,False),(2,True),(3,False),(4,True),(5,False)]

```

In fact, we can use our model to define a property-based test which asserts that

our queue deployment is faithful to the model:

```haskell

prop_commute :: Eq b => P a b -> [a] -> PropertyM IO ()

prop_commute p xs = do

ys <- run $ do

qxs <- newTQueueIO

mapM_ (atomically . writeTQueue qxs) xs

qys <- deploy p qxs

replicateM (length xs) (atomically (readTQueue qys))

assert (model p xs == ys)

```

Actually running this property for arbitrary pipelines would require us to first

define a pipeline generator, which is a bit tricky given the indexes of the

datatype[^4]. It can still me used as a helper for testing specific pipelines

though, e.g. `prop_commute examplePipeline`.

A bigger problem is that we've spawned two threads, when deploying `:&&&`, whose

mere job is to copy elements from the input queue (`xs`) to the input queues of

`f` and `g` (`xs{1,2}`), and from the outputs of `f` and `g` (`ys` and `zs`) to

the output of `f &&& g` (`ysz`). Copying data is expensive.

When we shard a pipeline we effectively clone it and send half of the traffic to

one clone and the other half to the other. One way to achieve this is as

follows, notice how in `shard` we swap `qEven` and `qOdd` when we recurse:

```haskell

deploy (Shard f) xs = do

xsEven <- newTQueueIO

xsOdd <- newTQueueIO

_pid <- forkIO (shard xs xsEven xsOdd)

ysEven <- deploy f xsEven

ysOdd <- deploy f xsOdd

ys <- newTQueueIO

_pid <- forkIO (merge ysEven ysOdd ys)

return ys

where

shard :: TQueue a -> TQueue a -> TQueue a -> IO ()

shard qIn qEven qOdd = do

atomically (readTQueue qIn >>= writeTQueue qEven)

shard qIn qOdd qEven

merge :: TQueue a -> TQueue a -> TQueue a -> IO ()

merge qEven qOdd qOut = do

atomically (readTQueue qEven >>= writeTQueue qOut)

merge qOdd qEven qOut

```

This alteration will shard the input queue (`qIn`) on even and odd indices, and

we can `merge` it back without losing determinism. Note that if we'd simply had

a pool of worker threads taking items from the input queue and putting them on

the output queue (`qOut`) after processing, then we wouldn't have a

deterministic outcome. Also notice that in the `deploy`ment of `Shard`ing we

also end up copying data between the queues, similar to the fan-out case

(`:&&&`)!

Before we move on to show how to avoid doing this copying, let's have a look at

a couple of examples to get a better feel for pipelining and sharding. If we

generalise `Map` to `MapM` in our

[model](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/ModelIO.hs)

we can write the following contrived program:

```haskell

modelSleep :: P () ()

modelSleep =

MapM (const (threadDelay 250000)) :&&& MapM (const (threadDelay 250000)) :>>>

MapM (const (threadDelay 250000)) :>>>

MapM (const (threadDelay 250000))

```

The argument to `threadDelay` (or sleep) is microseconds, so at each point in

the pipeline we are sleeping 1/4 of a second.

If we feed this pipeline `5` items:

```haskell

runModelSleep :: IO ()

runModelSleep = void (model modelSleep (replicate 5 ()))

```

We see that it takes roughly 5 seconds:

```

> :set +s

> runModelSleep

(5.02 secs, 905,480 bytes)

```

This is expected, even though we pipeline and fan-out, as the model is completely

sequential.

If we instead run the same pipeline using the queue deployment, we get:

```

> runQueueSleep

(1.76 secs, 907,160 bytes)

```

The reason for this is that the two sleeps in the fan-out happen in parallel now

and when the first item is at the second stage the first stage starts processing

the second item, and so on, i.e. we get a pipelining parallelism.

If we, for some reason, wanted to achieve a sequential running time using the

queue deployment, we'd have to write a one stage pipeline like so:

```haskell

queueSleepSeq :: P () ()

queueSleepSeq =

MapM $ \() -> do

() <- threadDelay 250000

((), ()) <- (,) <$> threadDelay 250000 <*> threadDelay 250000

() <- threadDelay 250000

return ()

```

```

> runQueueSleepSeq

(5.02 secs, 898,096 bytes)

```

Using sharding we can get an even shorter running time:

```haskell

queueSleepSharded :: P () ()

queueSleepSharded = Shard queueSleep

```

```

> runQueueSleepSharded

(1.26 secs, 920,888 bytes)

```

This is pretty much where we left off in my previous post. If the speed ups we

are seeing from pipelining don't make sense, it might help to go back and reread

the [old post](https://stevana.github.io/pipelined_state_machines.html), as I

spent some more time constructing an intuitive example there.

## Disruptor

Before we can understand how the Disruptor can help us avoid the problem copying

between queues that we just saw, we need to first understand a bit about how the

Disruptor is implemented.

We will be looking at the implementation of the single-producer Disruptor,

because in our pipelines there will never be more than one producer per queue

(the stage before it)[^5].

Let's first have a look at the datatype and then explain each field:

```haskell

data RingBuffer a = RingBuffer

{ capacity :: Int

, elements :: IOArray Int a

, cursor :: IORef SequenceNumber

, gatingSequences :: IORef (IOArray Int (IORef SequenceNumber))

, cachedGatingSequence :: IORef SequenceNumber

}

newtype SequenceNumber = SequenceNumber Int

```

The Disruptor is a ring buffer queue with a fixed `capacity`. It's backed by an

array whose length is equal to the capacity, this is where the `elements` of the

ring buffer are stored. There's a monotonically increasing counter called the

`cursor` which keeps track of how many elements we have written. By taking the

value of the `cursor` modulo the `capacity` we get the index into the array

where we are supposed to write our next element (this is how we wrap around the

array, i.e. forming a ring). In order to avoid overwriting elements which have

not yet been consumed we also need to keep track of the cursors of all consumers

(`gatingSequences`). As an optimisation we cache where the last consumer is

(`cachedGatingSequence`).

The API from the producing side looks as follows:

```haskell

tryClaimBatch :: RingBuffer a -> Int -> IO (Maybe SequenceNumber)

writeRingBuffer :: RingBuffer a -> SequenceNumber -> a -> IO ()

publish :: RingBuffer a -> SequenceNumber -> IO ()

```

We first try to claim `n :: Int` slots in the ring buffer, if that fails

(returns `Nothing`) then we know that there isn't space in the ring buffer and

we should apply backpressure upstream (e.g. if the producer is a web server, we

might want to temporarily rejecting clients with status code 503). Once we

successfully get a sequence number, we can start writing our data. Finally we

publish the sequence number, this makes it available on the consumer side.

The consumer side of the API looks as follows:

```haskell

addGatingSequence :: RingBuffer a -> IO (IORef SequenceNumber)

waitFor :: RingBuffer a -> SequenceNumber -> IO SequenceNumber

readRingBuffer :: RingBuffer a -> SequenceNumber -> IO a

```

First we need to add a consumer to the ring buffer (to avoid overwriting on wrap

around of the ring), this gives us a consumer cursor. The consumer is

responsible for updating this cursor, the ring buffer will only read from it to

avoid overwriting. After the consumer reads the cursor, it calls `waitFor` on

the read value, this will block until an element has been `publish`ed on that

slot by the producer. In the case that the producer is ahead it will return the

current sequence number of the producer, hence allowing the consumer to do a

batch of reads (from where it currently is to where the producer currently is).

Once the consumer has caught up with the producer it updates its cursor.

Here's an example which hopefully makes things more concrete:

```haskell

example :: IO ()

example = do

rb <- newRingBuffer_ 2

c <- addGatingSequence rb

let batchSize = 2

Just hi <- tryClaimBatch rb batchSize

let lo = hi - (coerce batchSize - 1)

assertIO (lo == 0)

assertIO (hi == 1)

-- Notice that these writes are batched:

mapM_ (\(i, c) -> writeRingBuffer rb i c) (zip [lo..hi] ['a'..])

publish rb hi

-- Since the ring buffer size is only two and we've written two

-- elements, it's full at this point:

Nothing <- tryClaimBatch rb 1

consumed <- readIORef c

produced <- waitFor rb consumed

-- The consumer can do batched reads, and only do some expensive

-- operation once it reaches the end of the batch:

xs <- mapM (readRingBuffer rb) [consumed + 1..produced]

assertIO (xs == "ab")

-- The consumer updates its cursor:

writeIORef c produced

-- Now there's space again for the producer:

Just 2 <- tryClaimBatch rb 1

return ()

```

See the `Disruptor` [module](src/Disruptor.hs) in case you are interested in the

implementation details.

Hopefully by now we've seen enough internals to be able to explain why the

Disruptor performs well. First of all, by using a ring buffer we only allocate

memory when creating the ring buffer, it's then reused when we wrap around the

ring. The ring buffer is implemented using an array, so the memory access

patterns are predictable and the CPU can do prefetching. The consumers don't

have a copy of the data, they merely have a pointer (the sequence number) to how

far in the producer's ring buffer they are, which allows for fanning out or

sharding to multiple consumers without copying data. The fact that we can batch

on both the write side (with `tryClaimBatch`) and on the reader side (with

`waitFor`) also helps. All this taken together contributes to the Disruptor's

performance.

## Disruptor pipeline deployment

Recall that the reason we introduced the Disruptor was to avoid copying elements

of the queue when fanning out (using the `:&&&` combinator) and sharding.

The idea would be to have the workers we fan-out to both be consumers of the

same Disruptor, that way the inputs don't need to be copied. Avoiding to copy

the individual outputs from the worker's queues (of `a`s and `b`s) into the

combined output (of `(a, b)`s) is a bit trickier.

One way, that I think works, is to do something reminiscent what

[`Data.Vector`](https://hackage.haskell.org/package/vector) does for pairs.

That's a vector of pairs (`Vector (a, b)`) is actually represented as a pair of

vectors (`(Vector a, Vector b)`)[^6].

We can achieve this with [associated

types](http://simonmar.github.io/bib/papers/assoc.pdf) as follows:

```haskell

class HasRB a where

data RB a :: Type

newRB :: Int -> IO (RB a)

tryClaimBatchRB :: RB a -> Int -> IO (Maybe SequenceNumber)

writeRingBufferRB :: RB a -> SequenceNumber -> a -> IO ()

publishRB :: RB a -> SequenceNumber -> IO ()

addGatingSequenceRB :: RB a -> IO Counter

waitForRB :: RB a -> SequenceNumber -> IO SequenceNumber

readRingBufferRB :: RB a -> SequenceNumber -> IO a

```

The instances for this class for types that are not pairs will just use the

Disruptor that we defined above.

```haskell

instance HasRB String where

data RB String = RB (RingBuffer String)

newRB n = RB <$> newRingBuffer_ n

...

```

While the instance for pairs will use a pair of Disruptors:

```haskell

instance (HasRB a, HasRB b) => HasRB (a, b) where

data RB (a, b) = RBPair (RB a) (RB b)

newRB n = RBPair <$> newRB n <*> newRB n

...

```

The `deploy` function for the fan-out combinator can now avoid copying:

```haskell

deploy :: (HasRB a, HasRB b) => P a b -> RB a -> IO (RB b)

deploy (p :&&& q) xs = do

ys <- deploy p xs

zs <- deploy q xs

return (RBPair ys zs)

```

Sharding, or partition parallelism as Jim calls it, is a way to make a copy of a

pipeline and divert half of the events to the first copy and the other half to

the other copy. Assuming there are enough unused CPUs/core, this could

effectively double the throughput. It might be helpful to think of the events at

even positions in the stream going to the first pipeline copy while the events

in the odd positions in the stream go to the second copy of the pipeline.

When we shard in the `TQueue` deployment of pipelines we end up copying events

from the original stream into the two pipeline copies. This is similar to

copying when fanning out, which we discussed above, and the solution is similar.

First we need to change the pipeline type so that the shard constructor has an

output type that's `Sharded`.

```diff

data P :: Type -> Type -> Type where

...

- Shard :: P a b -> P a b

+ Shard :: P a b -> P a (Sharded b)

```

This type is in fact merely the identity type:

```haskell

newtype Sharded a = Sharded a

```

But it allows us to define a `HasRB` instance which does the sharding without

copying as follows:

```haskell

instance HasRB a => HasRB (Sharded a) where

data RB (Sharded a) = RBShard Partition Partition (RB a) (RB a)

readRingBufferRB (RBShard p1 p2 xs ys) i

| partition i p1 = readRingBufferRB xs i

| partition i p2 = readRingBufferRB ys i

...

```

The idea being that we split the ring buffer into two, like when fanning out,

and then we have a way of taking an index and figuring out which of the two ring

buffers it's actually in.

This partitioning information, `p`, is threaded though while deploying:

```haskell

deploy (Shard f) p xs = do

let (p1, p2) = addPartition p

ys1 <- deploy f p1 xs

ys2 <- deploy f p2 xs

return (RBShard p1 p2 ys1 ys2)

```

For the details of how this works see the following footnote[^7] and the `HasRB

(Sharded a)` instance in the following

[module](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/RingBufferClass.hs).

If we

[run](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/LibMain/Sleep.hs)

our sleep pipeline from before using the Disruptor

[deployment](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/Pipeline.hs)

we get similar timings as with the queue deployment:

```

> runDisruptorSleep False

(2.01 secs, 383,489,976 bytes)

> runDisruptorSleepSharded False

(1.37 secs, 286,207,264 bytes)

```

In order to get a better understanding of how not copying when fanning out and

sharding improves performance, let's instead have a look at this pipeline which

fans out five times:

```haskell

copyP :: P () ()

copyP =

Id :&&& Id :&&& Id :&&& Id :&&& Id

:>>> Map (const ())

```

If we deploy this pipeline using queues and feed it five million items we get

the following statistics from the profiler:

```

11,457,369,968 bytes allocated in the heap

198,233,200 bytes copied during GC

5,210,024 bytes maximum residency (27 sample(s))

4,841,208 bytes maximum slop

216 MiB total memory in use (0 MB lost due to fragmentation)

real 0m8.368s

user 0m10.647s

sys 0m0.778s

```

While the same setup but using the Disruptor deployment gives us:

```

6,629,305,096 bytes allocated in the heap

110,544,544 bytes copied during GC

3,510,424 bytes maximum residency (17 sample(s))

5,090,472 bytes maximum slop

214 MiB total memory in use (0 MB lost due to fragmentation)

real 0m5.028s

user 0m7.000s

sys 0m0.626s

```

So about an half the amount of bytes allocated in the heap using the Disruptor.

If we double the fan-out factor from five to ten, we get the following stats with

the queue deployment:

```

35,552,340,768 bytes allocated in the heap

7,355,365,488 bytes copied during GC

31,518,256 bytes maximum residency (295 sample(s))

739,472 bytes maximum slop

257 MiB total memory in use (0 MB lost due to fragmentation)

real 0m46.104s

user 3m35.192s

sys 0m1.387s

```

and the following for the Disruptor deployment:

```

11,457,369,968 bytes allocated in the heap

198,233,200 bytes copied during GC

5,210,024 bytes maximum residency (27 sample(s))

4,841,208 bytes maximum slop

216 MiB total memory in use (0 MB lost due to fragmentation)

real 0m8.368s

user 0m10.647s

sys 0m0.778s

```

So it seems that the gap between the two deployments widens as we introduce more

fan-out, this expected as the queue implementation will have more copying of

data to do[^8].

## Observability

Given that pipelines are directed acyclic graphs and that we have a concrete

datatype constructor for each pipeline combinator, it's relatively straight

forward to add a visualisation of a deployment.

Furthermore, since each Disruptor has a `cursor` keeping that of how many

elements it produced and all the consumers of a Disruptor have one keeping track

of how many elements they have consumed, we can annotate our deployment

visualisation with this data and get a good idea of the progress the pipeline is

making over time as well as spot potential bottlenecks.

Here's an example of such an visualisation, for a

[word count](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/LibMain/WordCount.hs)

pipeline, as an interactive SVG (you need to click on the image):

[](https://stevana.github.io/svg-viewer-in-svg/wordcount-pipeline.svg)

The way it's implemented is that we spawn a separate thread that read the

producer's cursors and consumer's gating sequences (`IORef SequenceNumber` in

both cases) every millisecond and saves the `SequenceNumber`s (integers). After

collecting this data we can create one dot diagram for every time the data

changed. In the demo above, we also collected all the elements of the Disruptor,

this is useful for debugging (the implementation of the pipeline library), but

it would probably be too expensive to enable this when there's a lot of items to

be processed.

I have written a separate write up on how to make the SVG interactive over

[here](https://stevana.github.io/visualising_datastructures_over_time_using_svg.html).

## Running

All of the above Haskell code is available on

[GitHub](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/). The easiest way

to install the right version of GHC and cabal is probably via

[ghcup](https://www.haskell.org/ghcup/). Once installed the

[examples](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/tree/main/src/LibMain)

can be run as follows:

```bash

cat data/test.txt | cabal run uppercase

cat data/test.txt | cabal run wc # word count

```

The [sleep

examples](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/LibMain/Sleep.hs)

are run like this:

```bash

cabal run sleep

cabal run sleep -- --sharded

```

The different [copying

benchmarks](https://github.com/stevana/pipelining-with-disruptor/blob/main/src/LibMain/Copying.hs)

can be reproduced as follows:

```bash

for flag in "--no-sharding" \

"--copy10" \

"--tbqueue-no-sharding" \

"--tbqueue-copy10"; do \

cabal build copying && \

time cabal run copying -- "$flag" && \

eventlog2html copying.eventlog && \

ghc-prof-flamegraph copying.prof && \

firefox copying.eventlog.html && \

firefox copying.svg

done

```

## Further work and contributing

There's still a lot to do, but I thought it would be a good place to stop for

now. Here are a bunch of improvements, in no particular order:

- [ ] Implement the `Arrow` instance for Disruptor `P`ipelines, this isn't as

straightforward as in the model case, because the combinators are littered

with `HasRB` constraints, e.g.: `(:&&&) :: (HasRB b, HasRB c) => P a b ->

P a c -> P a (b, c)`. Perhaps taking inspiration from

constrained/restricted monads? In the `r/haskell` discussion, the user

`ryani` [pointed

out](https://old.reddit.com/r/haskell/comments/19ef2b6/parallel_stream_processing_with_zerocopy_fanout/kjhfyfk/)

a promising solution involving adding `Constraint`s to the `HasRB` class.

This would allow us to specify pipelines using the [arrow

notation](https://ghc.gitlab.haskell.org/ghc/doc/users_guide/exts/arrows.html).

- [ ] I believe the current pipeline combinator allow for arbitrary directed

acyclic graphs (DAGs), but what if feedback cycles are needed? Does an

`ArrowLoop` instance make sense in that case?

- [ ] Can we avoid copying when using `Either` via `(:|||)` or `(:+++)`, e.g.

can we store all `Left`s in one ring buffer and all `Right`s in another?

- [ ] Use unboxed arrays for types that can be unboxed in the `HasRB` instances?

- [ ] In the word count example we get an input stream of lines, but we only

want to produce a single line as output when we reach the end of the input

stream. In order to do this I added a way for workers to say that

`NoOutput` was produced in one step. Currently that constructor still gets

written to the output Disruptor, would it be possible to not write it but

still increment the sequence number counter?

- [ ] Add more monitoring? Currently we only keep track of the queue length,

i.e. saturation. Adding service time, i.e. how long it takes to process an

item, per worker shouldn't be hard. Latency (how long an item has been

waiting in the queue) would be more tricky as we'd need to annotate and

propagate a timestamp with the item?

- [ ] Since monitoring adds a bit of overheard, it would be neat to be able to

turn monitoring on and off at runtime;

- [ ] The `HasRB` instances are incomplete, and it's not clear if they need to

be completed? More testing and examples could help answer this question,

or perhaps a better visualisation?

- [ ] Actually test using `prop_commute` partially applied to a concrete

pipeline?

- [ ] Implement a property-based testing generator for pipelines and test using

`prop_commute` using random pipelines?

- [ ] Add network/HTTP source and sink?

- [ ] Deploy across network of computers?

- [ ] Hot-code upgrades of workers/stages with zero downtime, perhaps continuing

on my earlier

[attempt](https://stevana.github.io/hot-code_swapping_a_la_erlang_with_arrow-based_state_machines.html)?

- [ ] In addition to upgrading the workers/stages, one might also want to rewire

the pipeline itself. Doug made me aware of an old

[paper](https://inria.hal.science/inria-00306565) by Gilles Kahn and David

MacQueen (1976), where they reconfigure their network on the fly. Perhaps

some ideas can be stole from there?

- [ ] Related to reconfiguring is to be able shard/scale/reroute pipelines and

add more machines without downtime. Can we do this automatically based on

our monitoring? Perhaps building upon my earlier

[attempt](https://stevana.github.io/elastically_scalable_thread_pools.html)?

- [ ] More benchmarks, in particular trying to confirm that we indeed don't

allocate when fanning out and sharding[^8], as well as benchmarks against

other streaming libraries.

If any of this seems interesting, feel free to get involved.

## See also

* Guy Steele's talk [How to Think about Parallel Programming:

Not!](https://www.infoq.com/presentations/Thinking-Parallel-Programming/)

(2011);

* [Understanding the Disruptor, a Beginner's Guide to Hardcore

Concurrency](https://youtube.com/watch?v=DCdGlxBbKU4) by Trisha Gee and Mike

Barker (2011);

* Mike Barker's [brute-force solution to Guy's problem and

benchmarks](https://github.com/mikeb01/folklore/tree/master/src/main/java/performance);

* [Streaming 101: The world beyond

batch](https://www.oreilly.com/radar/the-world-beyond-batch-streaming-101/)

(2015);

* [Streaming 102: The world beyond

batch](https://www.oreilly.com/radar/the-world-beyond-batch-streaming-102/)

(2016);

* [*SEDA: An Architecture for Well-Conditioned Scalable Internet

Services*](https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~brewer/papers/SEDA-sosp.pdf)

(2001);

* [Microsoft

Naiad](https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/naiad-a-timely-dataflow-system-2/):

a timely dataflow system (with stage notifications) (2013);

* Elixir's ALF flow-based programming

[library](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2XrYd1W5GLo) (2021);

* [How fast are Linux pipes anyway?](https://mazzo.li/posts/fast-pipes.html)

(2022);

* [netmap](https://man.freebsd.org/cgi/man.cgi?query=netmap&sektion=4): a

framework for fast packet I/O;

* [The output of Linux pipes can be

indeterministic](https://www.gibney.org/the_output_of_linux_pipes_can_be_indeter)

(2019);

* [Programming Distributed Systems](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mc3tTRkjCvE)

by Mae Milano (Strange Loop, 2023);

* [Pipeline-oriented programming](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ipceTuJlw-M)

by Scott Wlaschin (NDC Porto, 2023).

## Discussion

* [discourse.haskell.org](https://discourse.haskell.org/t/parallel-stream-processing-with-zero-copy-fan-out-and-sharding/8632);

* [r/haskell](https://old.reddit.com/r/haskell/comments/19ef2b6/parallel_stream_processing_with_zerocopy_fanout/);

* [lobste.rs](https://lobste.rs/s/mvgdev/parallel_stream_processing_with_zero).

[^1]: I noticed that the Wikipedia page for [dataflow

programming](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dataflow_programming) mentions

that Jack Dennis and his graduate students pioneered that style of

programming while he was at MIT in the 60s. I knew Doug was at MIT around

that time as well, and so I sent an email to Doug asking if he knew of

Jack's work. Doug replied saying he had left MIT by the 60s, but was still

collaborating with people at MIT and was aware of Jack's work and also

the work by Kelly, Lochbaum and Vyssotsky on

[BLODI](https://archive.org/details/bstj40-3-669) (1961) was on his mind

when he wrote the garden hose memo (1964).

[^2]: There's a paper called [Parallel Functional Reactive

Programming](http://flint.cs.yale.edu/trifonov/papers/pfrp.pdf) by Peterson

et al. (2000), but as Conal Elliott

[points](http://conal.net/papers/push-pull-frp/push-pull-frp.pdf) out:

> "Peterson et al. (2000) explored opportunities for parallelism in

> implementing a variation of FRP. While the underlying semantic

> model was not spelled out, it seems that semantic determinacy was

> not preserved, in contrast to the semantically determinate concurrency

> used in this paper (Section 11)."

Conal's approach (his Section 11) seems to build upon very fine grained

parallelism provided by an "unambiguous choice" operator which is implemented

by spawning two threads. I don't understand where exactly this operator is

used in the implementation, but if it's used every time an element is

processed (in parallel) then the overheard of spawning the threads could

be significant?

[^3]: The design space of what pipeline combinators to include in the pipeline

datatype is very big. I've chosen the ones I've done because they are

instances of already well established type classes:

```haskell

instance Category P where

id = Id

g . f = f :>>> g

instance Arrow P where

arr = Map

f *** g = f :*** g

f &&& g = f :&&& g

instance ArrowChoice P where

f +++ g = f :+++ g

f ||| g = f :||| g

```

Ideally we'd also like to be able to use `Arrow` notation/syntax to describe our

pipelines. Even better would be if arrow notation worked for Cartesian categories.

See Conal Elliott's work on [compiling to

categories](http://conal.net/papers/compiling-to-categories/), as well as

Oleg Grenrus' GHC

[plugin](https://github.com/phadej/overloaded/blob/master/src/Overloaded/Categories.hs)

that does the right thing and translates arrow syntax into Cartesian

categories.

[^4]: Search for "QuickCheck GADTs" if you are interested in finding out more

about this topic.

[^5]: The Disruptor also comes in a multi-producer variant, see the following

[repository](https://github.com/stevana/pipelined-state-machines/tree/main/src/Disruptor/MP)

for a Haskell version or the

[LMAX](https://github.com/LMAX-Exchange/disruptor) repository for the

original Java implementation.

[^6]: See also [array of structures vs structure of

arrays](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AoS_and_SoA) in other programming

languages.

[^7]: The partitioning information consists of the total number of partitions

and the index of the current partition.

```haskell

data Partition = Partition

{ pIndex :: Int

, pTotal :: Int

}

```

No partitioning is represented as follows:

```haskell

noPartition :: Partition

noPartition = Partition 0 1

```

While creating a new partition is done as follows:

```haskell

addPartition :: Partition -> (Partition, Partition)

addPartition (Partition i total) =

( Partition i (total * 2)

, Partition (i + total) (total * 2)

)

```

So, for example, if we partition twice we get:

```

> let (p1, p2) = addPartition noPartition in (addPartition p1, addPartition p2)

((Partition 0 4, Partition 2 4), (Partition 1 4, Partition 3 4))

```

From this information we can compute if an index is in an partition or not as

follows:

```haskell

partition :: SequenceNumber -> Partition -> Bool

partition i (Partition n total) = i `mod` total == 0 + n

```

To understand why this works, it might be helpful to consider the case where we

only have two partitions. We can partition on even or odd indices as follows:

``even i = i `mod` 2 == 0 + 0`` and ``odd i = i `mod` 2 == 0 + 1``. Written this

way we can easier see how to generalise to `total` partitions: ``partition i

(Partition n total) = i `mod` total == 0 + n``. So for `total = 2` then

`partition i (Partition 0 2) == even` while `partition i (Partition 1 2) ==

odd`.

Since partitioning and partitioning a partition, etc, always introduce a power

of two we can further optimise to use bitwise or as follows: `partition i

(Partition n total) = i .|. (total - 1) == 0 + n` thereby avoiding the expensive

modulus computation. This is a trick used in Disruptor as well, and the reason

why the capacity of a Disruptor always needs to be a power of two.

[^8]: I'm not sure why "bytes allocated in the heap" gets doubled in the

Disruptor case and tripled in the queue cases though?