https://github.com/susam/emfy

A dark and sleek Emacs setup for general purpose editing and programming

https://github.com/susam/emfy

dark-theme emacs emacs-initialization emacs-lisp markdown minimalist paredit rainbow-delimiters

Last synced: about 1 month ago

JSON representation

A dark and sleek Emacs setup for general purpose editing and programming

- Host: GitHub

- URL: https://github.com/susam/emfy

- Owner: susam

- License: mit

- Created: 2021-12-29T16:31:18.000Z (over 3 years ago)

- Default Branch: main

- Last Pushed: 2024-09-09T07:56:24.000Z (8 months ago)

- Last Synced: 2024-10-30T00:32:17.402Z (7 months ago)

- Topics: dark-theme, emacs, emacs-initialization, emacs-lisp, markdown, minimalist, paredit, rainbow-delimiters

- Language: Emacs Lisp

- Homepage:

- Size: 102 KB

- Stars: 938

- Watchers: 16

- Forks: 38

- Open Issues: 1

-

Metadata Files:

- Readme: README.md

- Changelog: CHANGES.md

- License: LICENSE.md

Awesome Lists containing this project

README

Emacs for You (Emfy)

====================

This project provides a tiny [`init.el`] file to set up Emacs quickly.

This document provides a detailed description of how to set it up and

get started with Emacs.

[![View Source][Source SVG]][Source URL]

[![Mastodon][Mastodon SVG]][Mastodon URL]

[Source SVG]: https://img.shields.io/badge/view-init.el-brightgreen

[Source URL]: init.el

[Mastodon SVG]: https://img.shields.io/badge/mastodon-%40susam-%2355f

[Mastodon URL]: https://mastodon.social/@susam

[`init.el`]: init.el

[`em`]: em

Further this project also provides a tiny convenience command named

[`em`] to start Emacs server and edit files using Emacs server. This

helps in using Emacs efficiently. This script and its usage is

explained in detail later in the [Emacs Server](#emacs-server) and

[Emacs Launcher](#emacs-launcher) sections. Here is how the Emacs

environment is going to look after setting up this project:

[![Screenshot of Emacs][demo-img]][demo-img]

[demo-img]: https://susam.github.io/blob/img/emfy/emfy-0.4.0.png

If you are already comfortable with Emacs and only want to understand

the content of [`init.el`] or [`em`], you can skip ahead directly to

the [Line-by-Line Explanation](#line-by-line-explanation) section that

describes every line of these files in detail.

Contents

--------

* [Who Is This For?](#who-is-this-for)

* [Features](#features)

* [Get Started](#get-started)

* [Step-by-Step Usage](#step-by-step-usage)

* [Use Emacs](#use-emacs)

* [Use Paredit](#use-paredit)

* [Evaluate Emacs Lisp Code](#evaluate-emacs-lisp-code)

* [Use Rainbow Delimiters](#use-rainbow-delimiters)

* [Useful Terms](#useful-terms)

* [Line-by-Line Explanation](#line-by-line-explanation)

* [Tweak UI](#tweak-ui)

* [Dark Theme](#dark-theme)

* [Highlight Parentheses](#highlight-parentheses)

* [Minibuffer Completion](#minibuffer-completion)

* [Show Stray Whitespace](#show-stray-whitespace)

* [Require Final Newline](#require-final-newline)

* [Single Space for Sentence Spacing](#single-space-for-sentence-spacing)

* [Indentation](#indentation)

* [Keep Working Directory Tidy](#keep-working-directory-tidy)

* [Custom Command and Key Sequences](#custom-command-and-key-sequences)

* [Emacs Server](#emacs-server)

* [Install Packages](#install-packages)

* [Configure Paredit](#configure-paredit)

* [Configure Rainbow Delimiters](#configure-rainbow-delimiters)

* [End of File](#end-of-file)

* [Emacs Launcher](#emacs-launcher)

* [Opinion References](#opinion-references)

* [Channels](#channels)

* [License](#license)

* [See Also](#see-also)

Who Is This For?

----------------

Are you an absolute beginner to Emacs? Are you so new to Emacs that

you do not even have the `~/.emacs.d/` directory on your file system?

Have you come across recommendations to use starter kits like Doom

Emacs, Spacemacs, etc. but then you wondered if you could use vanilla

Emacs and customise it slowly to suit your needs without having to

sacrifice your productivity in the initial days of using Emacs? Do

you also want your Emacs to look sleek from day zero? If you answered

"yes" to most of these questions, then this project is for you.

The [`init.el`] file in this project provides a quick way to get

started with setting up your Emacs environment. This document

explains how to do so in a step-by-step manner. This document also

explains the content of [`init.el`] and [`em`] in a line-by-line

manner.

Note that many customisations in the Emacs initialisation file

available in this project are a result of the author's preferences.

They may or may not match others' preferences. They may or may not

suit your taste and requirements. Wherever applicable, the pros and

cons of each customisation and possible alternatives are discussed in

this document. You are encouraged to read the line-by-line

explanation that comes later in this document, understand each

customisation, and modify the initialisation file to suit your needs.

Features

--------

This project provides a file named [`init.el`] that offers the

following features:

- Disable a few UI elements to provide a clean and minimal

look-and-feel.

- Show current column number in the mode line.

- Load a dark colour theme named Wombat.

- Customise the colour theme to accentuate the cursor, comments, and

search matches.

- Highlight matching parentheses.

- Enable Fido mode for automatic completion of minibuffer input.

- Show trailing whitespace at the end of lines clearly.

- Show trailing newlines at the end of buffer clearly.

- Show missing newlines at the end of buffer clearly.

- Always add a newline automatically at the end of a file while

saving.

- Use single spacing convention to end sentences.

- Use spaces, not tabs, for indentation.

- Configure indentation settings according to popular coding

conventions.

- Move auto-save files and backup files to a separate directory to

keep our working directories tidy.

- Do not move original files while creating backups.

- Provide examples of user-defined custom commands and a few custom

key sequences.

- Start Emacs server automatically, so that terminal users can use

Emacs client to edit files with an existing instance of Emacs.

- Custom command to install configured packages conveniently.

- Install Markdown mode for convenient editing of Markdown files.

- Install and configure Paredit for editing S-expressions

efficiently.

- Install and configure Rainbow Delimiters to colour parentheses by

their nesting depth level.

Additionally, this project also provides a convenience command named

[`em`] that is a thin wrapper around the `emacs` and `emacsclient`

commands. It offers the following features:

- Start a new instance of Emacs when requested.

- Open files in an existing Emacs server if a server is running

already.

- Automatically start a new Emacs server if a server is not running

already.

All of these features along with every line of code that enables these

features are explained in the sections below.

Get Started

-----------

This section helps you to set up Emfy quickly and see what the end

result looks like. Perform the following steps to get started:

1. Install Emacs 28.1 or later.

On macOS, enter the following command if you have

[Homebrew](https://brew.sh):

```sh

brew install --cask emacs

```

On Debian, Ubuntu, or another Debian-based Linux system, enter the

following command:

```sh

sudo apt-get install emacs

```

For other environments, visit https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/

to see how to install Emacs.

2. Copy the Emacs initialisation file [`init.el`] provided here to

your home directory. Here is an example `curl` command that does

this:

```sh

mkdir ~/.emacs.d

curl -L https://github.com/susam/emfy/raw/main/init.el >> ~/.emacs.d/init.el

```

Here is another alternative that copies the initialisation file to

an XDG-compatible location as follows:

```sh

mkdir -p ~/.config/emacs

curl -L https://github.com/susam/emfy/raw/main/init.el >> ~/.config/emacs/init.el

```

Some Emacs users who have been using Emacs for a long time like to

keep the initialisation file at its traditional location

illustrated below:

```sh

curl -L https://github.com/susam/emfy/raw/main/init.el >> ~/.emacs

```

Emacs can automatically load the Emacs initialisation file from

any of the paths used above. See section [The Emacs

Initialisation File][emacs-init-doc] of the Emacs manual for more

details about this.

3. Copy the Emacs launcher script [`em`] provided here to some

directory that belongs to your `PATH` variable. For example, here

are a few commands that download this script and place it in the

`/usr/local/bin/` directory:

```sh

curl -L https://github.com/susam/emfy/raw/main/em > /tmp/em

sudo mv /tmp/em /usr/local/bin/em

chmod +x /usr/local/bin/em

```

The usefulness of this launcher script will be explained in the

section [Emacs Launcher](#emacs-launcher) later.

4. Install packages configured in Emfy:

```sh

emacs --eval '(progn (install-packages) (kill-emacs))'

```

We will see how this command works later in the section [Install

Packages](#install-packages).

On macOS, you may receive the following error message in a dialog

box: '“Emacs.app” can’t be opened because Apple cannot check it

for malicious software.' To resolve this issue, go to Apple menu >

System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General and click "Open

Anyway".

5. Start Emacs:

```sh

emacs

```

Now that your environment is setup, read the next section to learn how

to use this environment in more detail.

[emacs-init-doc]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/emacs/Init-File.html

Step-by-Step Usage

------------------

### Use Emacs

Emacs is a very powerful and extensible editor. It comes with over

10,000 built-in commands. A small section like this can barely

scratch the surface of Emacs. Yet, this section makes a modest

attempt at getting you started with Emacs and then provides more

resources to learn further. Perform the following steps to get

started:

1. Start Emacs:

```sh

emacs

```

2. Within Emacs, enter the following command to open a file, say,

`hello.txt`:

```

C-x C-f hello.txt RET

```

A new buffer to edit `hello.txt` is created. If a file with that

name already exists on your file system, then it loads the content

of the file into the buffer.

Note that in the Emacs world (and elsewhere too), the notation

`C-` denotes the ctrl modifier key. Thus `C-x` denotes

ctrl+x.

The notation `RET` denotes the enter or

return key.

Typing consecutive `C-` key sequences can be optimised by pressing

and holding down the ctrl key, then typing the other

keys, and then releasing the ctrl key. For example, to

type `C-x C-f`, first press and hold down ctrl, then

type x, then type f, and then release

ctrl. In other words, think of `C-x C-f` as `C-(x f)`.

This shortcut works for other modifier keys too.

3. Now type some text into the buffer. Type out at least 3-4 words.

We will need it for the next two steps.

4. Move backward by one word with the following key sequence:

```

M-b

```

The notation `M-` denotes the meta modifier key. The above

command can be typed with alt+b or

option+b or esc b.

If you face any issue with the alt key or the

option key, read [Emacs Wiki: Meta Key

Problems](https://www.emacswiki.org/emacs/MetaKeyProblems).

5. Now move forward by one word with the following key sequence:

```

M-f

```

5. The `C-g` key sequence cancels the current command. This can be

used when you mistype a command and want to start over or if you

type a command partially, then change your mind and then you want

to cancel the partially typed command. Try out these examples:

```

C-x C-f C-g

```

```

C-x C-g

```

7. Save the buffer to a file on the file system with this command:

```

C-x C-s

```

8. Quit Emacs:

```

C-x C-c

```

Now you know how to start Emacs, open a file, save it, and quit.

Improve your Emacs knowledge further by taking the Emacs tutorial that

comes along with Emacs. In Emacs, type `C-h t` to start the tutorial.

The key bindings to perform various operations like creating file,

saving file, quitting the editor, etc. may look arcane at first, but

repeated usage of the key bindings develops muscle memory soon and

after having used them for a few days, one does not even have to think

about them. The fingers do what the mind wants effortlessly due to

muscle memory.

While you are getting used to the Emacs key bindings, keep this [GNU

Emacs Reference Card][emacs-ref] handy. Also, if you are using it in

GUI mode, then the menu options can be quite helpful.

[emacs-ref]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/refcards/pdf/refcard.pdf

### Use Paredit

Paredit helps in keeping parentheses balanced and also in performing

structured editing of S-expressions in Lisp code. It provides a

powerful set of commands to manipulate S-expressions in various ways.

Perform the following steps to get started with Paredit:

1. Run Emacs:

```sh

emacs

```

2. Open an Emacs Lisp source file:

```

C-x C-f foo.el

```

3. Type the following code only:

```elisp

(defun square (x

```

At this point, Paredit should have inserted the two closing

parentheses automatically. The code should look like this:

```elisp

(defun square (x))

-

```

The cursor should be situated just after the parameter `x`. The

underbar shows where the cursor should be.

4. Type the closing parentheses now. Yes, type it even if the

closing parenthesis is already present. The cursor should now

skip over the first closing parenthesis like this:

```elisp

(defun square (x))

-

```

Of course, there was no need to type the closing parenthesis

because it was already present but typing it out to skip over it

is more efficient than moving over it with movement commands.

This is, in fact, a very nifty feature of Paredit. We can enter

code with the same keystrokes as we would without Paredit.

5. Now type enter to insert a newline just before the last

parenthesis. A newline is inserted like this:

```elisp

(defun square (x)

)

-

```

6. Now type only this:

```elisp

(* x x

```

Again, Paredit would insert the closing parenthesis automatically.

The code should look like this now:

```elisp

(defun square (x)

(* x x))

-

```

There is a lot more to Paredit than this. To learn more, see [The

Animated Guide to Paredit][paredit-ref].

Note: While many Lisp programmers find Paredit very convenient and

powerful while manipulating S-expressions in Lisp code, there are a

few people who do not like Paredit because they find the Paredit

behaviour intrusive. See the [Opinion References](#opinion-references)

section for more discussion on this topic.

[paredit-ref]: http://danmidwood.com/content/2014/11/21/animated-paredit.html

### Evaluate Emacs Lisp Code

The previous section shows how to write some Emacs Lisp code and how

Paredit helps in keeping the parentheses balanced. In this section,

we will see how to execute some Emacs Lisp code.

1. Run Emacs:

```sh

emacs

```

2. Open an Emacs Lisp source file:

```

C-x C-f foo.el

```

3. Enter the following code:

```elisp

(defun square (x)

(* x x))

```

4. With the cursor placed right after the last closing parenthesis,

type `C-x C-e`. The name of the function defined should appear in

the echo area at the bottom. This confirms that the function has

been defined.

5. Now add the following code to the Emacs Lisp source file:

```elisp

(square 5)

```

6. Once again, with the cursor placed right after the last closing

parenthesis, type `C-x C-e`. The result should appear in the echo

area at the bottom.

### Use Rainbow Delimiters

There is not much to learn about using Rainbow Delimiters. In the

previous sections, you must have seen that as you type nested

parentheses, each parenthesis is highlighted with a different colour.

That is done by Rainbow Delimiters. It colours each parenthesis

according to its nesting depth level.

Note: Not everyone likes Rainbow Delimiters. Some people find

parentheses in multiple colours distracting. See the [Opinion

References](#opinion-references) section for more discussion on this

topic.

Useful Terms

------------

In this section, we clearly describe a few terms that we use later in

this document.

- *Frame*: The Emacs manual uses the term frame to mean a GUI

window, or a region of the desktop, or the terminal where Emacs is

displayed. We do not call it window in Emacs parlance because the

term "window" is reserved for another element discussed further

below in this list.

- *Menu bar*: An Emacs frame displays a menu bar at the very top.

It allows access to commands via a series of menus.

- *Echo area*: An Emacs frame displays an echo area at the very

bottom. The echo area displays informative messages.

- *Minibuffer*: The echo area is also used to display the

minibuffer, a special buffer where we can type and enter arguments

to commands, such as the name of a file to be edited after typing

the key sequence `C-x C-f`.

- *Tool bar*: On a graphical display, a tool bar is displayed

directly below the menu bar. The tool bar contains a row of icons

that provides quick access to several editing commands.

- *Window*: The main area of the frame between the menu bar or the

tool bar (if it exists) and the echo area contains one or more

windows. This is where we view or edit files. Each window

displays a *buffer*, i.e., the text or graphics we are editing or

viewing. By default, only one window is displayed when we start

Emacs. We can split this main area into multiple windows using

key sequences like `C-x 2`, `C-x 3`, etc. and then open different

files or buffers in different windows.

- *Mode line*: The last line of each window is a mode line. It

displays information about the buffer. For example, it shows the

name of the buffer, the line number at which the cursor is

currently present, etc.

- *Scroll bar*: On a graphicaly display, a scroll bar is displayed

on one side which can be used to scroll through the buffer.

There are many other peculiar terms found in the world of Emacs such

as the term *point* to refer to the current location of the cursor,

the term *kill* to cut text, the term *yank* to paste text, etc. but

we will not discuss them here for the sake of brevity. The meanings

of most such terms become obvious from the context when you encounter

them. The terms described above should be sufficient to understand

the line-by-line explanation presented in the next section.

Line-by-Line Explanation

------------------------

This section explains the [`init.el`] file provided here line-by-line.

### Tweak UI

The first few lines in our [`init.el`] merely tweak the Emacs user

interface. These are of course not essential for using Emacs.

However, many new Emacs users often ask how to customise the user

interface to add a good colour scheme and make it look minimal, so

this section indulges a little in customising the user interface.

Here is a line-by-line explanation of the UI tweaks in [`init.el`]:

- When Emacs runs in a GUI window, by default, it starts with a menu

bar, tool bar, and scroll bar. Some users like to hide them in

order to make the Emacs frame look clean and minimal. The

following lines disable the tool bar and scroll bar. The menu bar

is left enabled.

```elisp

(when (display-graphic-p)

(tool-bar-mode 0)

(scroll-bar-mode 0))

```

The `when` expression checks if Emacs is running with graphic

display before disabling the tool bar and scroll bar. Without the

`when` expression, we get the following error on Emacs without

graphic display support: `Symbol's function definition is void:

tool-bar-mode`. An example of Emacs without graphics support is

`emacs-nox` on Debian 10. Note that this is only an author's

preference. You may comment out one or more of these lines if you

want to retain the tool bar or scroll bar.

Some users like to hide the menu bar as well. To disable the menu

bar, include `(menu-bar-mode 0)` as top-level-expression (i.e.,

outside the `when` expression) in the initialisation file. Even

with the menu bar disabled, the menu can be accessed anytime by

typing ``. For beginners to Emacs, it is advisable to keep

the menu bar enabled because it helps in discovering new features.

- Inhibit the startup screen with the `Welcome to GNU Emacs` message

from appearing:

```elisp

(setq inhibit-startup-screen t)

```

If you are a beginner to Emacs, you might find the startup screen

helpful. It contains links to tutorial, manuals, common tasks,

etc. If you want to retain the startup screen, comment this line

out.

- Show column number in the mode line:

```elisp

(column-number-mode)

```

By default, Emacs shows only the current line number in the mode

line. For example, by default, Emacs may display something like

`L4` in the mode line to indicate that the cursor is on the fourth

line of the buffer. The above Emacs Lisp code enables column

number display in the mode line. With column number enabled,

Emacs may display something like `(4,0)` to indicate the cursor is

at the beginning of the fourth line.

### Dark Theme

In this section, we will choose a dark theme for Emacs. If you do not

like dark themes, you might want to stick with the default theme,

choose another theme, or skip this section.

- Load a beautiful dark colour theme known as `wombat`:

```elisp

(load-theme 'wombat)

```

If you want to check the other built-in themes, type `M-x

customize-themes RET`. A new window with a buffer named `*Custom

Themes*` appear. In this buffer, select any theme you want to

test. After you are done testing, you can close this new window

with `C-x 0`.

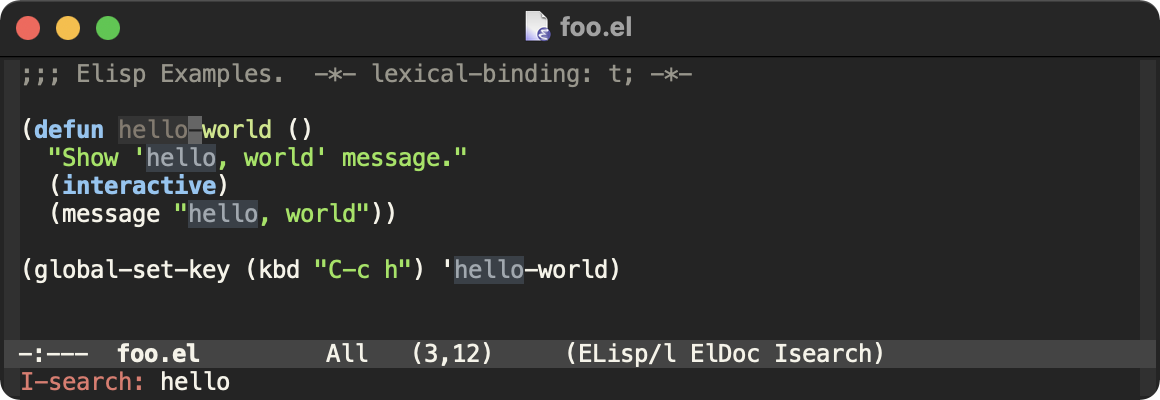

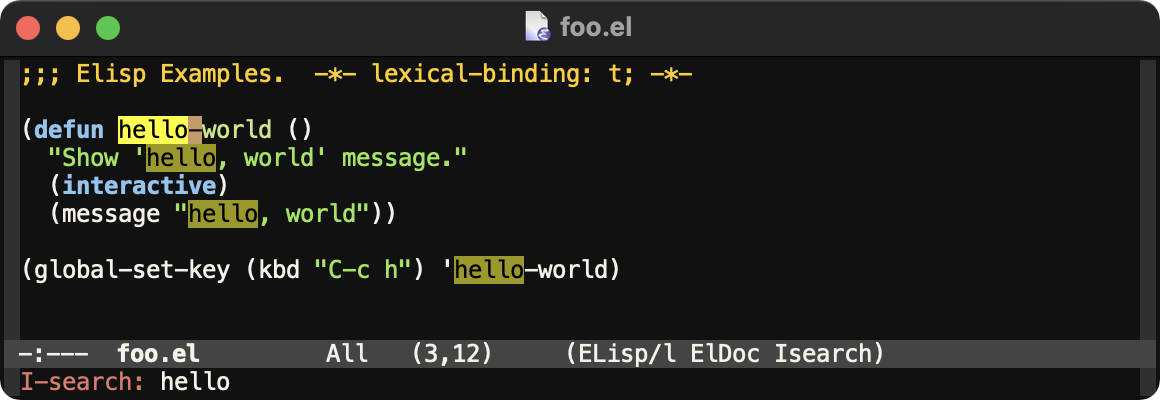

By default the Wombat theme looks like this:

In this theme, the cursor, search matches, and comments can often

be difficult to spot because they are all coloured with different

shades of grey while the background is also grey. In the next few

points, we will customise this theme a little to make these

elements easier to spot. We colour them differently to add more

contrast between the background and foreground colours of these

elements. In the end, our customised Wombat theme would look like

this:

- Choose a darker shade of grey for the background colour to improve

the contrast of the theme:

```elisp

(with-eval-after-load 'wombat-theme

(set-face-background 'default "#111")

```

The above `with-eval-after-load` expression ensures that the code

within its body is executed after `wombat-theme` gets loaded.

Since `wombat-theme` is already loaded here (due to the

`load-theme` expression discussed earlier), the body is evaluated

immediately. However, if `wombat-theme` were not yet loaded, the

body would be evaluated as soon as `wombat-theme` gets loaded.

The first expression in the the body sets the background colour to

`#111`, i.e., a very dark shade of grey.

The name `wombat-theme` refers to the feature provided by the

Wombat theme. Emacs packages (including the ones for themes) can

declare the feature they provide. If we ever remove or comment

out the `load-theme` expression mentioned earlier, then the

`wombat-theme` feature will not be loaded and the body of the

`with-eval-after-load` expression will not be executed.

Therefore, removing or commenting out the `load-theme` call is a

convenient way to disable the theme along with all the additional

color customizations made here.

- Choose a pale shade of orange for the cursor, so that it stands

out clearly against the dark grey background:

```elisp

(set-face-background 'cursor "#c96")

```

- Use tangerine yellow to colour the comments:

```elisp

(set-face-foreground 'font-lock-comment-face "#fc0")

```

- Highlight the current search match with bright yellow background

and dark foreground:

```elisp

(set-face-background 'isearch "#ff0")

(set-face-foreground 'isearch "#000")

```

- Highlight search matches other than the current one with a darker

shade of yellow as the background and dark foreground:

```elisp

(set-face-background 'lazy-highlight "#990")

(set-face-foreground 'lazy-highlight "#000"))

```

**Personal note:** I see that many recent colour themes choose a dim

colour for comments in code. Such colour themes intend to

underemphasise the comments. I think comments play an important role

in code meant to be read by humans and should be emphasised

appropriately. That's why I have chosen tangerine yellow for

comments. This makes the comments are easily readable.

### Line Numbers

Enable line numbers in modes for configuration, programming, and text

with the following loop:

```elisp

(dolist (hook '(prog-mode-hook conf-mode-hook text-mode-hook))

(add-hook hook 'display-line-numbers-mode))

```

Every buffer has a *major mode* which determines the editing

behaviour, syntax highlighting, etc. of the buffer. To see the

current major mode, type `M-: major-mode RET`. The name of the

current major mode is also always displayed in the mode line at the

bottom.

The `add-hook` calls in the loop above ensure that

`display-line-numbers-mode` is enabled automatically when certain

major modes become active. In particular, this ensures that line

numbers are enabled while editing configuration files, program files,

or text files. For instance, when editing a C program (say with `C-x

C-f foo.c RET`), the above hook enables line numbers for the buffer

for the C program file. This happens because while editing C program

files, the major mode named `c-mode` is activated and `c-mode` is

derived from `prog-mode`.

The above loop also ensures that this feature *does not* get enabled

while working with other types of buffers. For example, if we start a

terminal emulator with `M-x ansi-term RET`, this feature does not get

enabled because the terminal emulator buffer has the major mode named

`term-mode` which is not derived from any of the three modes mentioned

above. Displaying line numbers in such a mode can be distracting, so

we keep line numbers disabled in such modes.

### Highlight Parentheses

The following points describe how we enable highlighting of

parentheses:

- The next point shows how to enable highlighting of matching pair

of parentheses. By default, there is a small delay between the

movement of a cursor and the highlighting of the matching pair of

parentheses. The following line of code gets rid of this delay:

```elisp

(setq show-paren-delay 0)

```

This line of code must come before the one in the next point for

it to be effective.

- Highlight matching parentheses:

```elisp

(show-paren-mode)

```

A pair of parentheses is highlighted when the cursor is on the

opening parenthesis of the pair or just after the closing

parenthesis of the pair.

### Minibuffer Completion

Enable automatic minibuffer completion:

```elisp

(fido-vertical-mode)

```

To test this out, perform the following exercises:

- Type `C-x C-f /etc/hst` and watch Fido mode automatically

presenting `/etc/hosts` as one of the completion options. Type

`RET` to select it. Alternatively, type `C-n` and/or `C-p` to

pick a different option and type `RET`.

- Type `C-x b msg RET` and watch Fido presenting the buffer named

`*Messages*` as one of the options and selecting it. By the way,

the key sequence `C-x b` is used to switch buffers.

- Type `M-x wspmod RET` and watch Fido presenting the command named

`whitespace-mode` as one of the options and selecting it. The key

sequence `M-x` is used to execute Emacs commands. We will see

later how to make our own commands.

In the steps above, note how it is not necessary to type out the

filename or buffer name or command accurately. We can enter our input

partially and Fido will automatically find matches for it.

### Show Stray Whitespace

While writing text files, it can often be useful to quickly spot any

trailing whitespace at the end of lines or unnecessary trailing new

lines at the end of the file. The next few points describe how we

highlight stray whitespace and newlines.

- Highlight trailing whitespace at the end of lines in modes for

configuration, programming, and text with the following loop:

```elisp

(dolist (hook '(conf-mode-hook prog-mode-hook text-mode-hook))

(add-hook hook (lambda () (setq show-trailing-whitespace t))))

```

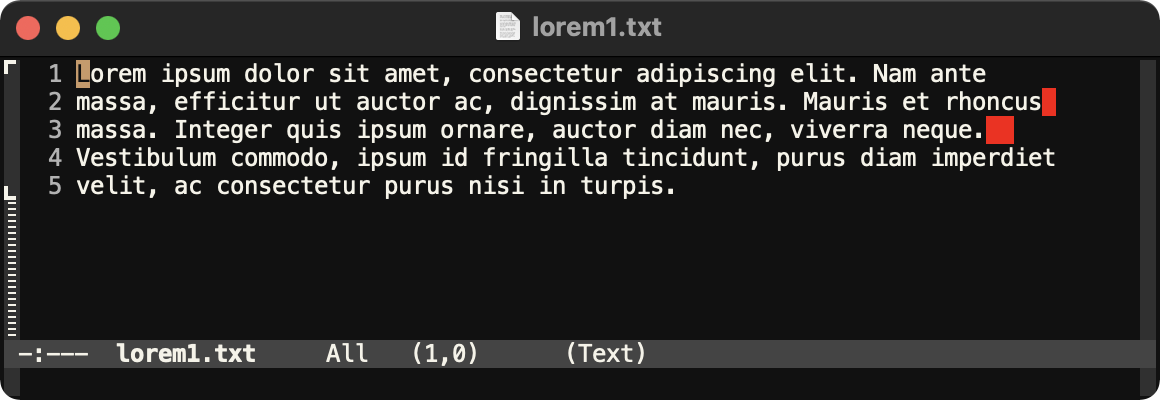

When the variable `show-trailing-whitespace` is set to `t`, any

stray trailing whitespace at the end of lines is highlighted

(usually with a red background) as shown in the screenshot below:

The screenshot above shows one stray trailing space in the second

line and two trailing spaces in the third line. These trailing

spaces can be removed with the key sequence `M-x

delete-trailing-whitespace RET`.

Note that we enable this feature only for modes pertaining to

configuration, programming, and text. It can be distracting to

see stray whitespace highlighted in other modes like `term-mode`,

`erc-mode`, etc.

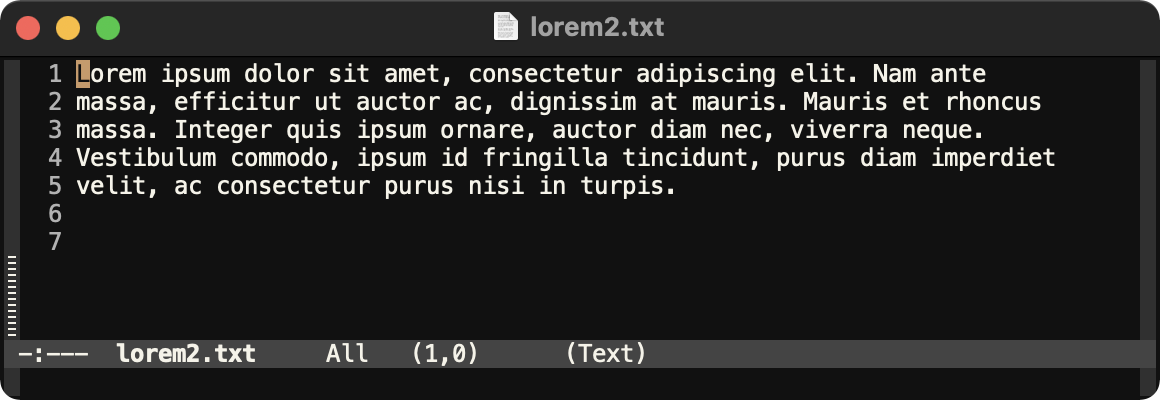

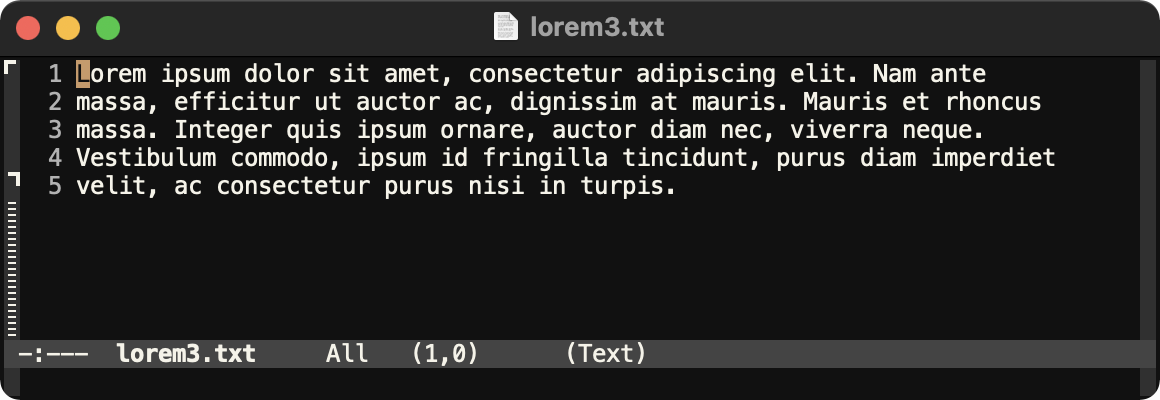

- Show the end of buffer with a special glyph in the left fringe:

```elisp

(setq-default indicate-empty-lines t)

```

Showing the end of the buffer conspicuously can be helpful to spot

any unnecessary blank lines at the end of a buffer. A blank line

is one that does not contain any character except the terminating

newline itself. Here is a screenshot that demonstrates this

feature:

The screenshot shows that there are two blank lines just before

the end of the buffer. The tiny horizontal dashes on the left

fringe mark the end of the buffer. Note: This is similar to how

Vim displays the tilde symbol (`~`) to show the end of the buffer.

The trailing blank lines at the end of a buffer can be removed

with the key sequence `M-x delete-trailing-whitespace RET`.

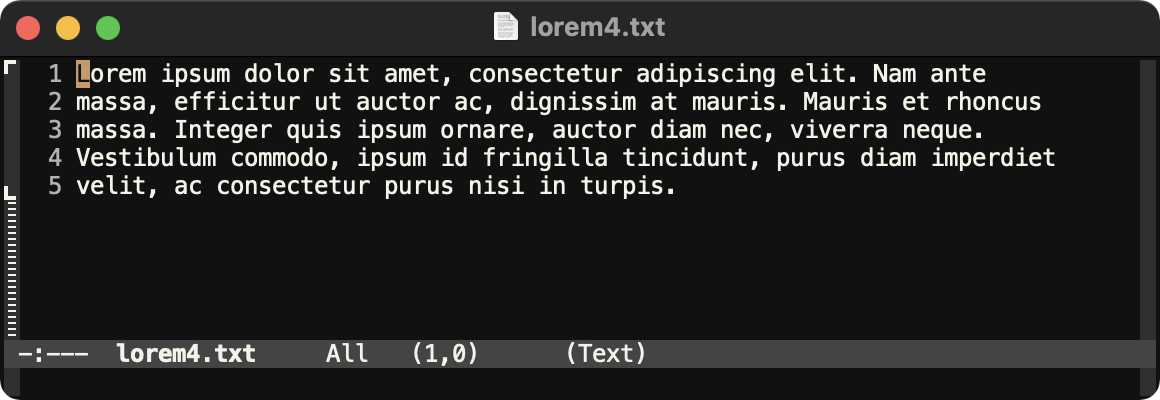

- Show buffer boundaries in the left fringe:

```elisp

(setq-default indicate-buffer-boundaries 'left)

```

The buffer boundaries can be useful to check if the last line of

the buffer has a terminating newline or not. If the buffer does

not contain a terminating newline, then a top-right corner shape

(`⌝`) appears in the fringe. For example, see this screenshot of

a file that does not contain a terminating newline:

If there is only one line in the buffer and that line is

terminated with a newline then a left-bracket (`[`) appears in the

fringe. If there are multiple lines in the buffer and the last

line is terminated with a newline then a bottom-left corner shape

(`⌞`) appears in the fringe. Here is a screenshot of a file that

contains a terminating newline:

To summarise, these shapes (`[`, `⌞`, or `⌝`) show where the last

newline of the buffer exists. The last newline of the buffer

exists above the lower horizontal bar of these shapes. No

newlines exist below the lower horizontal bar.

### Require Final Newline

It is good practice to terminate text files with a newline. For many

types of files, such as files with extensions `.c`, `.el`, `.json`,

`.lisp`, `.org`, `.py`, `.txt`, etc., Emacs inserts a terminating

newline automatically when we save the file with `C-x C-s`. Emacs

achieves this by ensuring that the major modes for these files set the

variable `require-final-newline` to `t` by default. However, there

are many other types of files, such as files with extensions `.ini`,

`.yaml`, etc. for which Emacs does not insert a terminating newline

automatically. We now ensure that Emacs always inserts a

terminating newline for all types of files with the following call:

```elisp

(setq require-final-newline t)

```

Many tools on Unix and Linux systems expect text files to be

terminated with a newline. For example, in a crontab entry, if the

final line is not followed by a terminating newline, it is ignored.

Similarly, `wc -l` does not count the final line if it is not followed

by a terminating newline. That is why, in the above step we configure

Emacs to ensure that it always inserts a terminating newline before

saving a file.

### Single Space for Sentence Spacing

Emacs uses the convention of treating a full stop followed by two

spaces as end of sentence. However, many people these days seem to

prefer ending sentences with a full stop followed by a single space.

This section explains how to configure Emacs to treat a full stop

followed by a single space as end of sentence.

If you like the convention of having two spaces after full stop, you

should remove the code discussed below from your Emacs initialisation

file and then skip this section. If you are unable to make up your

mind about whether you should end sentences with one space or two

spaces, read the final paragraph of this section for some discussion

about it.

We can configure Emacs to treat a sentence-terminating character (like

a full stop, question mark, etc.) followed by a single space as end of

sentence with the following code:

```elisp

(setq sentence-end-double-space nil)

```

This little setting has significant consequences while editing and

moving around text files. We will discuss two such consequences now

with two tiny experiments:

**Experiment A: Moving By Sentences:** To check the default behaviour,

first comment out the above line of Emacs Lisp code in the Emacs

initialisation file, save the file, and restart Emacs. Now copy the

following text:

```

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit donec. Porttitor id lacus non consequat.

```

Then open a new text buffer in Emacs with `C-x C-f foo.txt RET` and

paste the copied text with `C-y`. Then type `C-a` to go to the

beginning of the line. Finally, type `M-e` to move to the end of the

sentence. Without `sentence-end-double-space` set to `nil`, typing

`M-e` moves the cursor all the way to the end of the line (i.e., after

the second full stop). It ignores the first full stop as end of

sentence because it is followed by one space whereas Emacs expects two

spaces at the end of a sentence.

Now to verify that the above line of Emacs Lisp code works as

expected, uncomment it again to enable it, save the file, restart

Emacs, and then perform the above experiment again. With

`sentence-end-double-space` set to `nil`, typing `M-e` moves the

cursor to the end of the of first sentence (i.e., after the first full

stop). This is what we normally expect these days.

**Experiment B: Filling Paragraphs:** While writing text files, it is

customary to limit the length of each line to a certain maximum

length. In Emacs, the key sequence `M-q` invokes the `fill-paragraph`

command that works on the current paragraph and reformats it such that

each line is as long as possible without exceeding 70 characters in

length.

To check the default behaviour, first comment out the above line of

Emacs Lisp code in the Emacs initialisation file, save the file, and

restart Emacs. Then create the same text buffer as the one in the

previous experiment. Now place the cursor anywhere on text and type

`M-q` to reformat it as a paragraph. Without

`sentence-end-double-space` set to `nil`, typing `M-q` reformats the

paragraph as follows:

```

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit

donec. Porttitor id lacus non consequat.

```

Now to verify that the above line of Emacs Lisp code works as

expected, uncomment it again to enable it, save the file, then restart

Emacs, and then perform the above experiment again. With

`sentence-end-double-space` set to `nil`, typing `M-q` reformats the

paragraphs as follows:

```

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit donec.

Porttitor id lacus non consequat.

```

We see that without `sentence-end-double-space` set to `nil`, Emacs

refuses to insert a hard linebreak after the string `donec.`, so it

moves the entire word to the next line. This is a result of following

the convention of double spaces at the end of a sentence. This

convention prevents inadvertently placing a hard linebreak within an

abbreviation. Since many people prefer ending a sentence with a

single space, we would like the text above to be reformatted as shown

in the last example above. Setting `sentence-end-double-space` to

`nil` achieves this.

While the step above explains how to configure Emacs to treat a full

stop followed by a single space as the end of sentence, it is worth

mentioning here that the number of spaces that must follow the end of

a sentence is a very controversial matter. Many people prefer two

spaces between sentences while many others prefer a single space

instead. Section [Sentences][emacs-sentences-doc] of the Emacs manual

recommends putting two spaces at the end of a sentence because it

helps the Emacs commands that operate on sentences distinguish between

dots that end a sentence and those that do not. The author of this

project uses two spaces to end sentences. Also, see the [Opinion

References](#opinion-references) section for more discussion on this

topic. In case, you want to follow the convention of two spaces at

the end of a sentence, omit the above line of Emacs Lisp from your

Emacs initialisation file.

[emacs-sentences-doc]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/emacs/Sentences.html

### Indentation

The following point shows how to configure Emacs to insert spaces, not

tabs, for indenting code.

- Use spaces, not tabs, for indentation:

```elisp

(setq-default indent-tabs-mode nil)

```

Emacs uses a mix of tabs and spaces by default for indentation and

alignment. To verify the default behaviour, first comment out the

above line of Emacs Lisp code, save it, then restart Emacs, then

open a new Emacs Lisp source file, say, `C-x C-f foo.el RET` and

type the following three lines of Emacs Lisp code:

```elisp

(defun foo ()

(concat "foo"

"bar"))

```

While typing the above code, do not type tab or

space to indent the second and third lines. When you

type enter at the end of each line, Emacs automatically

inserts the necessary tabs and spaces to indent the code. After

entering this code, type `M-x whitespace-mode RET` to visualise

whitespace characters. This mode displays each space with a

middle dot (`·`) and each tab with a right pointing guillemet

(`»`). With whitespace mode enabled, you should find that the

second line of code is indented with two spaces but the third line

is indented with a single tab followed by two spaces. The buffer

should look like this:

```elisp

(defun·foo·()$

··(concat·"foo"$

» ··"bar"))

```

Emacs has a `tab-width` variable that is set to `8` by default.

For every `tab-width` columns of indentation, Emacs inserts a tab

to indent the code. The third line requires 10 leading spaces for

alignment, so Emacs inserts one tab character followed by two

spaces to make the third line look aligned. However, this code

would look misaligned with a different `tab-width` setting.

That's why we configure Emacs to use only spaces to indent and

align code.

Now to verify that the above line of Emacs Lisp code works as

expected, uncomment the function call to set `indent-tabs-mode` to

`nil`, save it, then restart Emacs, and then perform the above

experiment involving the three lines of Emacs Lisp code again.

This time, you should see that no tabs are used for indentation.

Only spaces are used for indentation. Typing `M-x whitespace-mode

RET` would display this in the buffer:

```elisp

(defun·foo·()$

··(concat·"foo"$

··········"bar"))

```

In some type of files, we must use literal tabs. For example, in

`Makefile`, the syntax of target rules require that the commands

under a target are indented by literal tab characters. In such

files, Emacs is smart enough to always use literal tabs for

indentation regardless of the above variable setting.

Mixing tabs and spaces for indenting source code can be

problematic, especially, when the author of code or Emacs

inadvertently uses tabs for alignment (as opposed to using tabs

for indentation only which would be fine) and another programmer

views the file with an editor with a different tab width setting.

In fact, in the experiment above, Emacs did use a literal tab

character to align code which would cause the code to look

misaligned on another editor with a different tab width setting.

See [Tabs Are Evil](https://www.emacswiki.org/emacs/TabsAreEvil)

for more details on this topic.

- Display the distance between two tab stops as whitespace that is

as wide as 4 characters:

```elisp

(setq-default tab-width 4)

```

Note that this primarily affects how a literal tab character is

displayed. Further, along with the previous variable setting

where we set `indent-tabs-mode` to `nil`, in some types of files,

this variable setting decides how many spaces are inserted when we

hit the tab key. For example, in text buffers, on

hitting the tab key, as many spaces are inserted as are

necessary to move the cursor to the next tab stop where the

distance between two tab stops is assumed to be `tab-width`.

In some type of files, we must use literal tabs. For example, in

`Makefile`, the syntax of target rules require that the commands

under a target are indented by a literal tab character. In such

files, Emacs displays the distance between two tab stops as

whitespace that is as wide as 8 characters by default. This

default setting is often too large for many users. They feel that

a tab width of 8 consumes too much horizontal space on the screen.

The variable setting above reduces the tab width to 4. Of course,

different users may have different preferences for the tab width.

Therefore, users are encouraged to modify this variable setting to

a value they prefer or omit the above line of Emacs Lisp code from

their Emacs initialisation file to leave it to the default value

of 8.

- Set indentation levels according to popular coding conventions for

various languages:

```elisp

(setq c-basic-offset 4)

(setq js-indent-level 2)

(setq css-indent-offset 2)

```

Emacs uses 2 spaces for indentation in C by default. We change

this to 4 spaces.

Emacs uses 4 spaces for indentation in JavaScript and CSS by

default. We change this to 2 spaces.

### Keep Working Directory Tidy

Emacs creates a number of temporary files to ensure that we do not

inadvertently lose our work while editing files. However, these files

can clutter our working directories. This section shows some ways to

keep the current working directory tidy by asking Emacs to manage

these files at a different location.

- Create a directory to keep auto-save files:

```elisp

(make-directory "~/.tmp/emacs/auto-save/" t)

```

In the next point, we discuss auto-save files in detail and ask

Emacs to write auto-save files to a separate directory instead of

writing them to our working directory. Before we do that, we need

to create the directory we will write the auto-save files to,

otherwise Emacs would fail to write the auto-save files and

display the following error: `Error (auto-save): Auto-saving

foo.txt: Opening output file: No such file or directory,

/Users/susam/.tmp/emacs/auto-save/#!tmp!foo.txt#`

Note that this issue occurs only for auto-save files, not for

backup files discussed in the third point of this list. If the

parent directory for backup files is missing, Emacs creates it

automatically. However, Emacs does not create the parent

directory for auto-save files automatically, so we need the above

line of Emacs Lisp code to create it ourselves.

- Write auto-save files to a separate directory:

```elisp

(setq auto-save-file-name-transforms '((".*" "~/.tmp/emacs/auto-save/" t)))

```

If we open a new file or edit an existing file, say, `foo.txt` and

make some changes that have not been saved yet, Emacs

automatically creates an auto-save file named `#foo.txt#` in the

same directory as `foo.txt` every 300 keystrokes, or after 30

seconds of inactivity. Emacs does this to ensure that the unsaved

changes are not lost inadvertently. For example, if the system

crashes suddenly while we are editing a file `foo.txt`, the

auto-save file would keep a copy of our unsaved worked. The next

time we try to edit `foo.txt`, Emacs would warn that auto-save

data already exists and it would then suggest us to recover the

auto-save data using `M-x recover-this-file RET`. These auto-save

files are removed automatically after we save our edits but until

then they clutter our working directories. The above line of

Emacs Lisp code ensures that all auto-save files are written to a

separate directory, thus leaving our working directories tidy.

- Write backup files to a separate directory:

```elisp

(setq backup-directory-alist '(("." . "~/.tmp/emacs/backup/")))

```

If we create a new file or edit an existing file, say, `foo.txt`,

then make some changes to it, and save it, the previous copy of

the file is saved as a backup file `foo.txt~`. These backup files

too clutter our working direcories. The above line of Emacs Lisp

code ensures that all backup files are written to a separate

directory, thus leaving our working directories tidy.

- Create backup files by copying our files, not moving our files:

```elisp

(setq backup-by-copying t)

```

Everytime Emacs has to create a backup file, it moves our file to

the backup location, then creates a new file at the same location

as that of the one we are editing, copies our content to this new

file, and then resumes editing our file. This causes any hard

link referring to the original file to be now referring to the

backup file.

To experience this problem due to the default behaviour, first

comment out the above line of Emacs Lisp code in the Emacs

initialisation file, save the file, and restart Emacs. Then

create a new file along with a hard link to it with these

commands: `echo foo > foo.txt; ln foo.txt bar.txt; ls -li foo.txt

bar.txt`. The output should show that `foo.txt` and `bar.txt`

have the same inode number and size because they both refer to the

same file. Now run `emacs foo.txt` to edit the file, add a line

or two to the file, and save the file with `C-x C-s`. Now run `ls

-li foo.txt bar.txt` again. The output should show that `foo.txt`

now has a new inode number and size while `bar.txt` still has the

original inode number and size. The file `bar.txt` now refers to

the backup file instead of referring to the new `foo.txt` file.

To see the improved behaviour with the above line of Emacs Lisp

code, uncomment it to enable it again in the Emacs initialisation

file, save the file, restart Emacs and perform the same experiment

again. After we save the file, we should see that both `foo.txt`

and `bar.txt` have the same inode number and size.

- Disable lockfiles:

```elisp

(setq create-lockfiles nil)

```

As soon as we make an edit to a file, say `foo.txt`, Emacs creates

a lockfile `.#foo.txt`. If we then launch another instance of

Emacs and try to edit this file, Emacs would refuse to edit the

file, then warn us that the file is locked by another Emacs

session, and provide us a few options regarding whether we want to

steal the lock, proceed with editing anyway, or quit editing it.

These lockfiles are removed automatically as soon as we save our

edits but until then they clutter our directories. Unlike

auto-save files and backup files, there is no way to tell Emacs to

write these files to a different directory. We can however

disable lockfile creation with the above line of Emacs Lisp code.

**Caution:** Note that disabling lockfiles could be risky if you

are in the habit of launching multiple Emacs instances while

editing files. With such a habit, it is easy to make the mistake

of opening the same file in two different Emacs instances and

inadvertently overwrite changes made via one instance with changes

made via another instance. The lockfiles are hidden files anyway,

so they should not bother you in directory listings. If they

bother you in, say, `git status` output, consider ignoring the

lockfiles in `.gitignore` instead of disabling them. Having said

that, it may be okay to disable lockfiles if you are in the habit

of launching only a single instance of Emacs for the entire

lifetime of their desktop session and edit all files via that

single instance. The [Emacs Server](#emacs-server) and [Emacs

Launcher](#emacs-launcher) sections later discuss techniques about

how to make this usage style more convenient. If you are willing

to follow this style of using Emacs, then it may be okay to

disable lockfiles. To summarise, if you are in doubt, comment out

or remove the above line of Emacs Lisp code to keep lockfiles

enabled.

- When we install packages using `package-install` (coming up soon

in a later section), a few customisations are written

automatically into the Emacs initialisation file (e.g., in

`~/.emacs.d/init.el`). This has the rather undesirable effect of

our carefully handcrafted `init.el` being meddled by

`package-install`. To be precise, it is the `custom` package

invoked by `package-install` that intrudes into our Emacs

initialisation file. To prevent that, we ask `custom` to write

the customisations to a separate file with the following code:

```elisp

(setq custom-file (concat user-emacs-directory "custom.el"))

```

- Emacs does not load the custom-file automatically, so we add the

following code to load it:

```elisp

(load custom-file t)

```

It is important to load the custom-file because it may contain

customisations we have written to it directly or via the customise

interface (say, using `M-x customize RET`). If we don't load this

file, then any customisations written to this file will not become

available in our Emacs environment.

The boolean argument `t` ensures that no error occurs when the

custom-file is missing. Without it, when Emacs starts for the

first time with our initialisation file and there is no

custom-file yet, the following error occurs: `File is missing:

Cannot open load file, No such file or directory,

~/.emacs.d/custom.el`. Setting the second argument to `t`

prevents this error when Emacs is run with our initialisation file

for the first time.

### Custom Command and Key Sequences

In this section we will see how to make our own custom command.

- Create a very simple custom command to display the current time in

the echo area at the bottom of the Emacs frame:

```elisp

(defun show-current-time ()

"Show current time."

(interactive)

(message (current-time-string)))

```

This creates an interactive function named `show-current-time`.

An interactive function is an Emacs command that can be invoked

with `M-x`. For example, the above command can be invoked by

typing `M-x show-current-time RET`. On running this command, the

current time appears in the echo area.

- Create a custom key sequence to invoke the command defined in the

previous point:

```elisp

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c t") 'show-current-time)

```

Now the same command can be invoked by typing `C-c t`.

- Create another custom key sequence to delete trailing whitespace

using the `delete-trailing-whitespace` introduced in the [Show

Stray Whitespace](#show-stray-whitespace) section:

```elisp

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c d") 'delete-trailing-whitespace)

```

Note that the custom key sequence in this point and the previous

one only serve as examples. You should define key sequences based

on your needs that you find more convenient.

### Emacs Server

Many users prefer to run a single instance of Emacs and do all their

editing activities via this single instance. It is possible to use

Emacs alone for all file browsing needs and never use the terminal

again. Despite the sophisticated terminal and file browsing

capabilities of Emacs, some users still like to use a traditional

terminal to move around a file system, find files, and edit them.

This practice may become inconvenient quite soon because it would lead

to the creation of too many Emacs frames (desktop-level windows) and

processes. This section explains how to create a single Emacs server,

a single Emacs frame, and edit all your files in this frame via the

server even while you are browsing files in the terminal. You don't

need this section if you use Emacs for all your file browsing needs

but if you don't, this section may be useful. Let us now see how we

start the Emacs server in our Emacs initialisation file.

- This is necessary to use the function `server-running-p` coming up

in the next point:

```elisp

(require 'server)

```

If we omit the above line of Emacs Lisp code, we will encounter

the following error when we try to use `server-running-p`

discussed in the next point: `Symbol’s function definition is

void: server-running-p`.

- If there is no Emacs server running, start an Emacs server:

```elisp

(unless (server-running-p)

(server-start))

```

The `unless` expression ensures that there is no Emacs server

running before starting a new Emacs server. If we omit the

`unless` expression, the following error would occur if an Emacs

server is already running: `Warning (server): Unable to start the

Emacs server. There is an existing Emacs server, named "server".

To start the server in this Emacs process, stop the existing

server or call ‘M-x server-force-delete’ to forcibly disconnect

it.`

Finally, the `server-start` function call starts an Emacs server.

When Emacs starts for the first time with the above lines of Emacs

Lisp code in its initialisation file, it starts an Emacs server. Now

the following commands can be used on a terminal to edit files:

- `emacs` or `emacs foo.txt bar.txt`: Starts another instance of

Emacs. It does not start a new server due to the `unless`

expression discussed above. Typically, we will not use this

because we don't want to launch a second instance of Emacs. But

it is good to know that this command still works as expected in

case we ever need it.

- `emacsclient foo.txt bar.txt`: Opens files in the existing Emacs

instance via the Emacs server. The command waits for us to finish

editing all the files. It blocks the terminal until then. When

we are done editing a file, we must type `C-x #` to tell Emacs to

switch to the next file. Once we are done editing all the files,

the `emacsclient` command exits and the shell prompt returns on

the terminal.

- `emacsclient -n foo.txt bar.txt`: Opens files in the existing

Emacs instance but does not wait for us to finish editing. The

command exits immediately and the shell prompt returns immediately

on the terminal.

With this setup, the Emacs server quits automatically when we close

the first Emacs instance that started the Emacs server. Running the

`emacs` command or starting Emacs via another method after that would

start the Emacs server again.

It is worth noting here that there are other ways to start the Emacs

server and to use the `emacsclient` command. See section [Using Emacs

as a Server][emacs-server-doc] and section [`emacsclient`

Options][emacs-client-doc] of the Emacs manual for more details.

[emacs-server-doc]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/emacs/Emacs-Server.html

[emacs-client-doc]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/emacs/emacsclient-Options.html

### Install Packages

The following points describe how we automate the installation of

Emacs packages we need:

- We begin defining a new command that we use to install external

packages automatically.

```elisp

(defun install-packages ()

"Install and set up packages for the first time."

(interactive)

(require 'package)

```

The `(require 'package)` line is necessary for defining the

`package-archives` list we will use in the next point.

- Add Milkypostman's Emacs Lisp Package Archive (MELPA) to the list

of archives to fetch packages from:

```elisp

(add-to-list 'package-archives '("melpa" . "https://melpa.org/packages/") t)

```

By default GNU Emacs Lisp Package Archive (ELPA) and NonGNU Emacs

Lisp Package Archive (NonGNU ELPA) are the only package archives

configured for fetching packages. The above line adds MELPA too

to the list of archives to fetch packages from. Although we are

not going to install any package from MELPA in this project, it is

common practice to include it as a package source. Adding MELPA

now ensures you are prepared to explore a broader range of

packages as your Emacs usage evolves.

- Download package descriptions from package archives:

```elisp

(package-refresh-contents)

```

See the `~/.emacs.d/elpa/archives` or `~/.config/emacs/elpa/archives`

directory for archive contents in case you are curious.

- Install some packages:

```elisp

(dolist (package '(markdown-mode paredit rainbow-delimiters))

(unless (package-installed-p package)

(package-install package))))

```

This loop iterates over each package name in a list of packages.

For each package, it checks whether the package is installed with

the `package-installed-p` function. If it is not installed, then

it is installed with the `package-install` function.

You can modify the list of packages in the first line to add other

packages that you might need in future or remove packages that you

do not need.

The code discussed above creates a new command named

`install-packages` that we can execute anytime with

`M-x install-packages RET`.

You can also add new packages to the list used in the `dolist` call,

type `C-M-x` to evaluate the `install-packages` function again, so

that this command is now updated according to your latest code, and

then run `M-x install-packages RET` to install the new packages.

Having understood this section, step 4 of the [Get

Started](#get-started) section should now make sense. The command we

used there was:

```sh

emacs --eval '(progn (install-packages) (kill-emacs))'

```

This command simply runs Emacs (with your Emacs initialisation file)

and evaluates an Emacs Lisp expression that runs the

`install-packages` function followed by `kill-emacs`. As a result,

this command installs the packages configured in the code discussed

above and quits Emacs.

**Alternative:** If you know enough Emacs already, you might notice

that this project does not use the `use-package` package. The

`use-package` package allows us to install and configure packages

declaratively such that the configuration of each package is neatly

contained within one `use-package` expression. The author of this

project has been using Emacs long before `use-package` existed and

prefers a more traditional method of installing and configuring

packages using `package.el` and `with-eval-after-load`. However, if

you want to explore installing and configuring packages declaratively,

please take a look at the [use-package User Manual][use-package].

[use-package]: https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/use-package/

### Configure Paredit

This section describes how to enable Paredit. Paredit helps in

keeping parentheses balanced and in performing structured editing of

S-expressions. Some Emacs Lisp programmers find it useful while some

do not.

In case you decide not to use Paredit, you may skip this section. In

that case, you might also want to remove this package from the

`dolist` loop discussed in the previous section.

We enable Paredit in various modes pertaining to Lisp programming with

the following Emacs Lisp code:

```elisp

(when (fboundp 'paredit-mode)

(dolist (hook '(emacs-lisp-mode-hook

eval-expression-minibuffer-setup-hook

ielm-mode-hook

lisp-interaction-mode-hook

lisp-mode-hook))

(add-hook hook 'enable-paredit-mode)))

```

Here is an explanation of the above code:

- The `when` expression checks if `paredit-mode` is available before

setting up hooks to enable it in various modes. If it is

unavailable, then the hooks are not set up.

- The `dolist` expression iterates over hooks for various modes

where we want Paredit to be enabled. In each iteration, the

`add-hook` expression adds the function `enable-paredit-mode` to

each mode's hook. This ensures that whenever one of these modes

gets activated, `enable-paredit-mode` is called thereby enabling

Paredit in that mode.

- Adding `enable-paredit-mode` to `emacs-lisp-mode-hook` enables

Paredit while editing Emacs Lisp code.

To test that Paredit is enabled while editing Emacs Lisp code,

open a new Emacs Lisp file, say, `foo.el`. Then type `(`.

Paredit should automatically insert the corresponding `)`.

- Adding `enable-paredit-mode` to `eval-expression-minibuffer-setup-hook`

enables Paredit in eval-expression minibuffer.

To test this, enter `M-:` to bring up the eval-expression minbuffer

and type `(`. Paredit should automatically insert the corresponding

`)`.

- Adding `enable-paredit-mode` to `ielm-mode-hook` enables Paredit

while interactively evaluating Emacs Lisp expressions in

`inferior-emacs-lisp-mode` (IELM).

To test this, enter `M-x ielm RET`. When the `*ielm*` buffer

appears, type `(`. Paredit should automatically insert the

corresponding `)`.

- Adding `enable-paredit-mode` to `lisp-interaction-mode-hook`

enables Paredit in Lisp interaction mode.

To test this, first open a non-Lisp file, say, `C-x C-f foo.txt

RET`. Now type `(`. Note that no corresponding `)` is inserted

because we are not in Lisp interaction mode yet. Delete `(`. Then

start Lisp interaction mode with the command `M-x

lisp-interaction-mode RET`. Type `(` again. Paredit should now

automatically insert the corresponding `)`.

- Adding `enable-paredit-mode` to `lisp-mode-hook` enables Paredit

while editing Lisp code other than Emacs Lisp.

To test this, open a new Common Lisp source file, say, `C-x C-f

foo.lisp RET`. Then type `(`. Paredit should automatically insert

the corresponding `)`.

By default, Paredit overrides the behaviour of the `RET` key such that

a newline is inserted whenever we press `RET` key. Unfortunately,

this behaviour is problematic in the eval-expression minibuffer and

IELM where we want to evaluate the expression we have entered when we

type `RET`. Therefore, we disable the overriding behaviour of Paredit

using the following code:

```elisp

(with-eval-after-load 'paredit

(define-key paredit-mode-map (kbd "RET") nil))

```

The above code ensures that whenever Paredit is loaded, the `RET`

key binding in its keymap is set to `nil`, so that Paredit does

not override the default behaviour of the `RET` key.

### Configure Rainbow Delimiters

This section describes how to enable rainbow delimiters and configure

it. Rainbow Delimiters colour nested parentheses with different

colours according to the depth level of each parenthesis. Some people

find it useful and some do not.

If you decide not to use Rainbow Delimiters, you may skip this

section. In that case, you might also want to remove this package

from the `dolist` loop discussed in the previous section.

We enable Paredit in various modes pertaining to Lisp programming with

the following Emacs Lisp code:

```elisp

(when (fboundp 'rainbow-delimiters-mode)

(dolist (hook '(emacs-lisp-mode-hook

ielm-mode-hook

lisp-interaction-mode-hook

lisp-mode-hook))

(add-hook hook 'rainbow-delimiters-mode)))

```

Here is an explanation of the above code:

- Then `when` expression checks if `rainbow-delimiters-mode` is

available before setting up hooks to enable it in various modes.

If it is unavailable, then the hooks are not set up.

- The `dolist` expression iterates over hooks for various modes

where we want Rainbow Delimiters to be enabled. In each

iteration, the `add-hook` expression adds the function

`rainbow-delimiters-mode` to each mode's hook. This ensures that

whenever one of these modes gets activated,

`rainbow-delimiters-mode` is called thereby enabling Rainbow

Delimiters in that mode.

- Adding `rainbow-delimiters-mode` to `emacs-lisp-mode-hook` enables

Rainbow Delimiters while editing Emacs Lisp code.

To test this open a new Emacs Lisp file, say, `foo.el`. Then type

`(((`. Rainbow Delimiters should colour each parenthesis

differently.

- Adding `rainbow-delimiters-mode` to `ielm-mode-hook` enables

Rainbow Delimiters while interactively evaluating Emacs Lisp

expressions in inferior-emacs-lisp-mode (IELM):

To test this, enter `M-x ielm RET`. When the `*ielm*` buffer comes

up, type `(((`. Rainbow Delimiters should colour each parenthesis

differently.

- Adding `rainbow-delimiters-mode` to `lisp-interaction-mode-hook`

enables Rainbow Delimiters in Lisp interaction mode.

To test this, first open a non-Lisp file, say, `foo.txt`. Now type

`(((`. Then start Lisp interaction mode with the command `M-x

lisp-interaction-mode RET`. Rainbow Delimiters should now colour each

parenthesis differently.

- Adding `rainbow-delimiters-mode` to `lisp-mode-hook` enables

Rainbow Delimiters while editing Lisp code other than Emacs Lisp:

To test this, open a new Common Lisp source file, say, `foo.lisp`.

Then type `(((`. Rainbow Delimiters should colour each parenthesis

differently.

In the discussion above, you may have noticed that we did not enable

Rainbow Delimiters for eval-expression minibuffer. That is because

eval-expression minibuffer does not support syntax highlightng.

Therefore enabling Rainbow Delimiters in it has no effect. See

https://github.com/Fanael/rainbow-delimiters/issues/57 for more

details.

The default colours that Rainbow Delimiters chooses for the nested

parentheses are too subtle to easily recognise the matching pair of

parentheses. The following Emacs Lisp code makes the parentheses more

colourful:

```elisp

(with-eval-after-load 'rainbow-delimiters

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-1-face "#c66") ; red

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-2-face "#6c6") ; green

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-3-face "#69f") ; blue

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-4-face "#cc6") ; yellow

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-5-face "#6cc") ; cyan

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-6-face "#c6c") ; magenta

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-7-face "#ccc") ; light gray

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-8-face "#999") ; medium gray

(set-face-foreground 'rainbow-delimiters-depth-9-face "#666")) ; dark gray

```

The colours chosen above make matching pairs of parentheses easier to

recognise.

### End of File

The final line of code in the file is:

```elisp

(provide 'init)

```

The above line is not really necessary for the Emacs initialisation

file. The `provide` function call declares a feature that an Emacs

package provides, so `provide` calls like the one above are typically

found in Emacs packages. Here, we simply declare that this Emacs

initialisation file provides a feature named `init`, only for the sake

of completeness.

Other Emacs Lisp programs can test whether a feature is availabe using

the `featurep` function. For example, Paredit provides the feature

named `paredit`. To test if this feature is available, type `M-:

(featurep 'paredit) RET`.

Similarly, to test if the `init` feature declared above is available,

type `M-: (featurep 'init) RET`

### Emacs Launcher

In the [Emacs Server](#emacs-server) section, we saw how our Emacs

initialisation file ensures that an Emacs server is started when we

run `emacs` for the first time. Once Emacs server has started, we can

edit new files from the terminal using the `emacsclient` command.

This section describes a script named `em` that can automatically

decide whether to run `emacs` or `emacsclient` depending on the

situation.

As mentioned in the previous section, you don't need this section if

you use Emacs for all your file browsing needs but if you don't, this

section may be useful. Further, it is worth mentioning that this

script solves a very specific problem of using a single command named

`em` to both launch a new Emacs server as well as to open existing

files in an existing Emacs frame via the existing Emacs server. If you

have this specific problem, you may find this script helpful. However,

if you do not have this problem or if you have a different problem to

solve, it would be useful to understand how `emacsclient` works and

read the related documentation mentioned in the previous section and

then modify this script or write your own shell script, shell alias,

or shell function that solves your problems.

The `em` script should be already present on the system if the steps

in the [Get Started](#get-started) section were followed. The third

step there installs this script to `/usr/local/bin/em`. Now we discuss

every line of this script in detail.

- When `em` is run without any arguments, start a new Emacs process:

```sh

#!/bin/sh

if [ "$#" -eq 0 ]

then

echo "Starting new Emacs process ..." >&2

nohup emacs &

```

This Emacs process launches a new Emacs frame. Further, if an

Emacs server is not running, it starts a new Emacs server. The

`nohup` command ensures that this Emacs process is not terminated

when we close the terminal or the shell where we ran the `em`

command.

- When `em` is run with one or more filenames as arguments and there

is an Emacs server already running, edit the files using the

existing Emacs server:

```sh

elif emacsclient -n "$@" 2> /dev/null

then

echo "Opened $@ in Emacs server" >&2

```

However, if there is no Emacs server already running, the above

command in the `elif` clause fails and the execution moves to the

`else` clause explained in the next point.

- When `em` is run with one or more filenames as arguments and there

is no Emacs server running, start a new Emacs process to edit the

files:

```sh

else

echo "Opening $@ in a new Emacs process ..." >&2

nohup emacs "$@" &

fi

```

The new Emacs process also starts a new Emacs server.

Now that we know what the `em` script does, let us see the various

ways of using this script as a command:

- `em`: Start a new instance of Emacs. If there is no Emacs server

running, this ends up starting an Emacs server too. Normally, this

command should be run only once after logging into the desktop

environment.

- `em foo.txt bar.txt`: Edit files in an existing instance of Emacs

via Emacs server. If no Emacs server is running, this ends up

starting an Emacs server automatically. This command is meant to

be used multiple times as needed for editing files while browsing

the file system in a terminal.

That's it! Only two things to remember from this section: start Emacs

with `em` and edit files with `em foo.txt`, `em foo.txt bar.txt`, etc.

Opinion References

------------------

- [Give paredit mode a chance][paredit-chance]

- [Never warmed up to paredit][paredit-never-warmed]

- [Coloring each paren differently only adds noise][rainbow-noise]

- [The drawbacks of using single space between sentences][single-space-drawbacks]

- [Why you should never, ever use two spaces after a period][space-invaders]

[paredit-chance]: https://stackoverflow.com/a/5243421/303363

[paredit-never-warmed]: https://lobste.rs/s/vgjknq/emacs_begin_learning_common_lisp#c_0y6zpd

[rainbow-noise]: https://lobste.rs/s/vgjknq/emacs_begin_learning_common_lisp#c_1n78vl

[single-space-drawbacks]: https://old.reddit.com/r/emacs/comments/p5zlr6/

[space-invaders]: https://slate.com/technology/2011/01/two-spaces-after-a-period-why-you-should-never-ever-do-it.html

Channels

--------

The following channels are available for asking questions, seeking

help and receiving updates regarding this project:

- GitHub: [emfy/issues](http://github.com/susam/emfy/issues)

- Mastodon: [@[email protected]](https://mastodon.social/@susam)

- Matrix: [#susam:matrix.org](https://matrix.to/#/#susam:matrix.org)

- Libera: [#susam](https://web.libera.chat/#susam)

You are welcome to follow or subscribe to one or more of these channels

to receive updates and ask questions about this project.

License

-------

This is free and open source software. You can use, copy, modify,

merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of it,

under the terms of the MIT License. See [LICENSE.md][L] for details.